Does Google know how Google works?

Platforms vs. LLMs. PLUS: "All Eyes on Rafah"

Greetings from Read Max HQ! In today’s newsletter:

The Google “AI Overview” fiasco, why it was so funny/depressing, and what it tells us about Google

A theory about the “All Eyes on Rafah” A.I.-generated Instagram image and why it (and not others) went viral

My pick for “most dangerous app”

An audio recording of this newsletter being read out loud by yours truly can be obtained at the button below, or from whatever fine app you use to listen to your podcasts:

A reminder! We are still in the midst of a WEEK-LONG SALES EVENT, THE READ MAX PAY FOR MY SON’S SUMMER CAMP SPECIAL, during which Read Max subscriptions are a whopping 20 percent off. This event ends on SUNDAY, which leaves you only a precious few hours to simultaneously save money and also help me obtain childcare for my son for July so I can continue shitposting as a career.

99 percent of Read Max’s revenue comes from paying subscribers, whose generosity and assistance allows me to treat this newsletter as a full-time job, giving me the time and space to undertake independent criticism and reporting, as well as the fun stuff that isn’t really any of those things. If you find the newsletter even minimally educational, entertaining, or helpful, considering subscribing--at the sales rate it’s less than the price of one (1) domestic bottled beer a month, depending on location.

Does Google know how Google works?

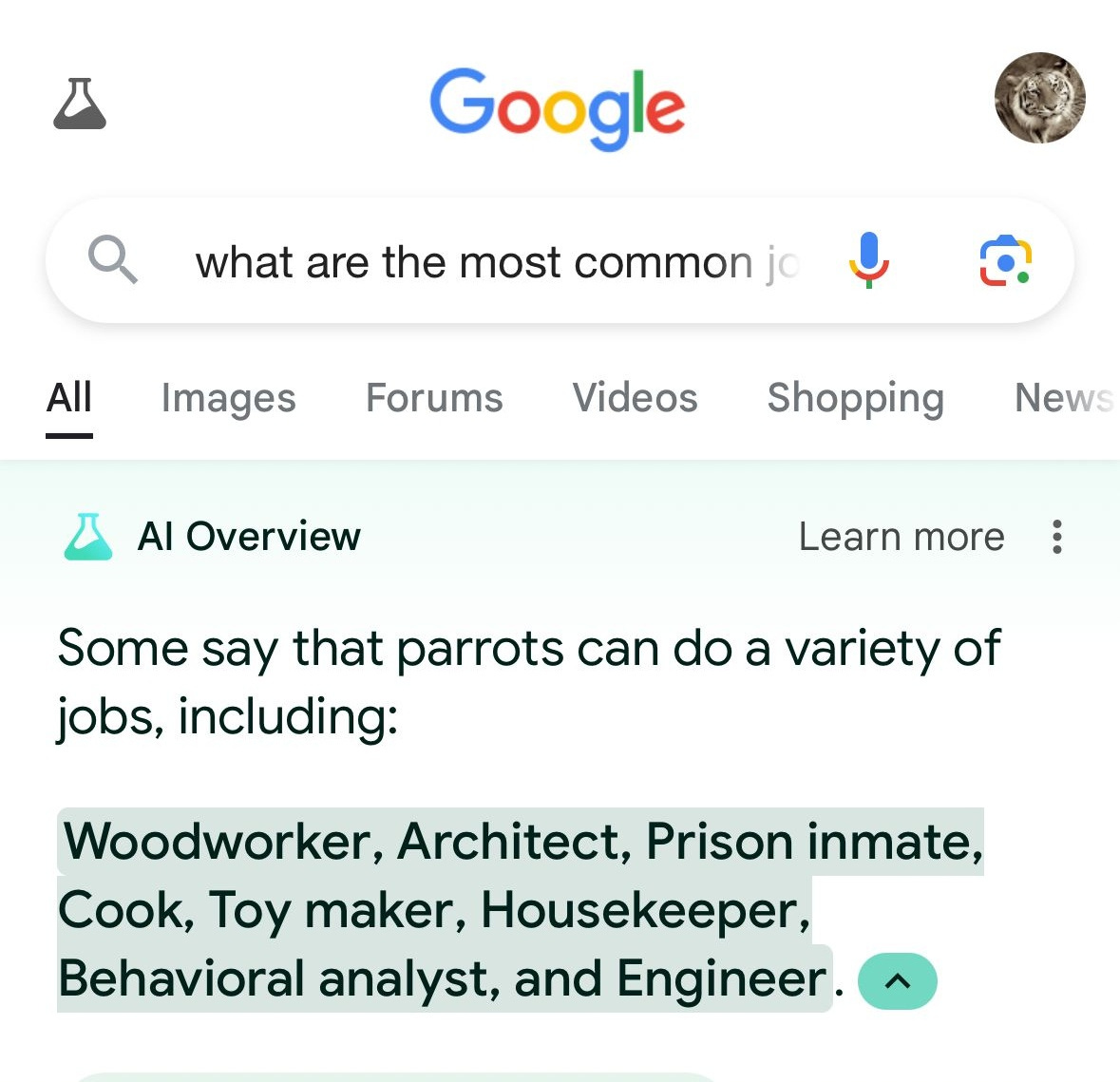

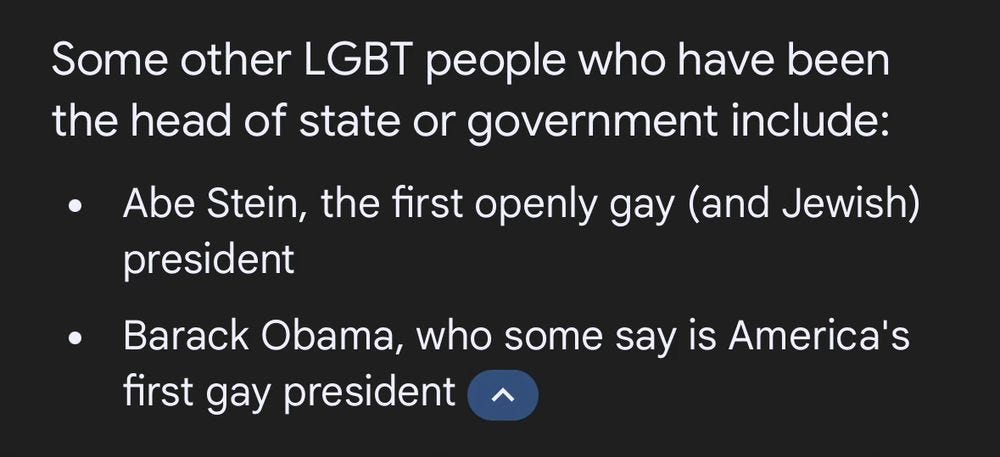

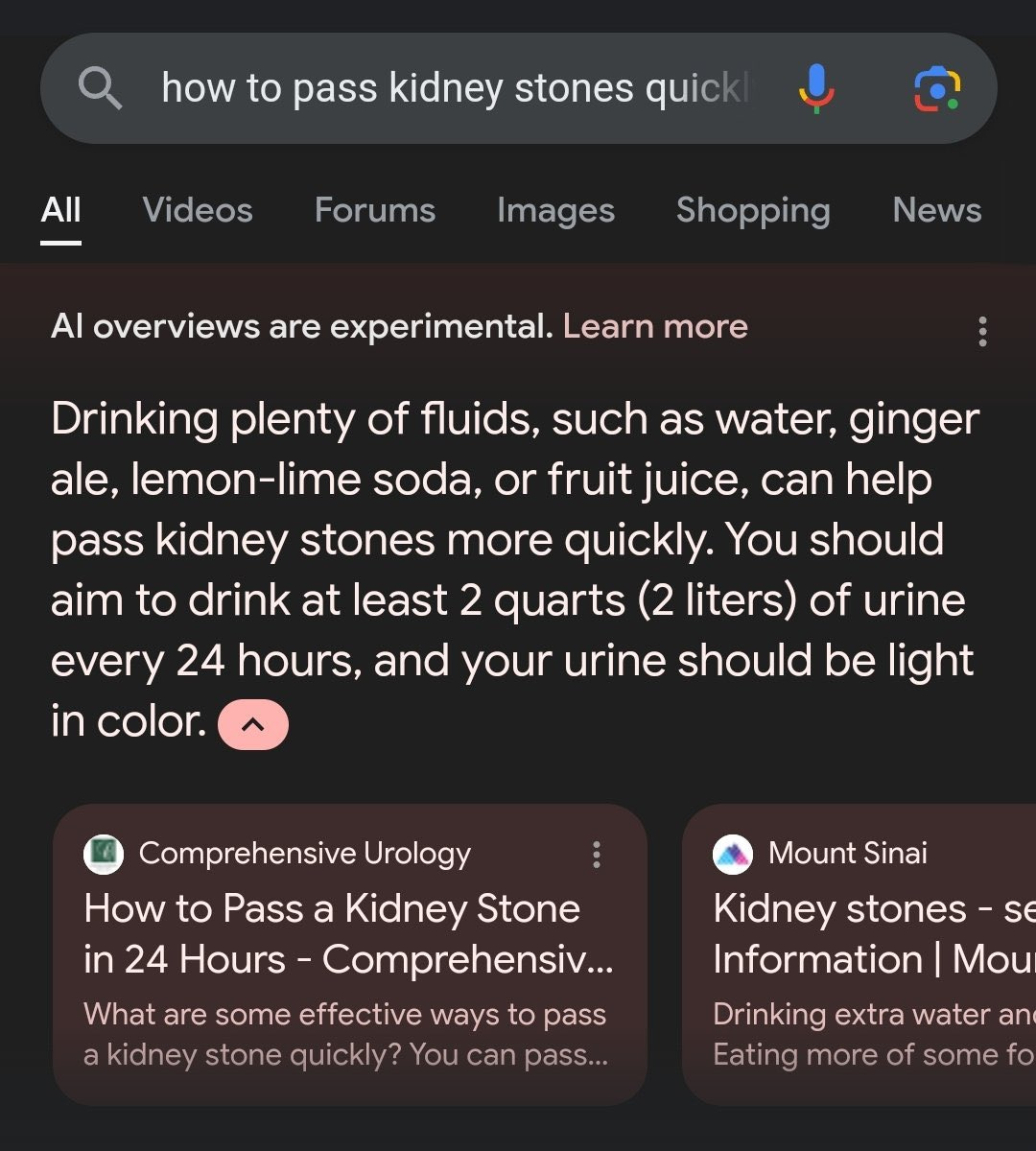

You’ve probably already seen many screenshots from the recent, life-affirmingly funny rollout of Google search’s new “AI Overview” feature, which uses a large language model (of the kind that powers ChatGPT, e.g.) to synthesize and summarize search results into a paragraph or two of text, placed prominently above the results. These “overviews,” synthesized from Google search results, are frequently incorrect or incoherent, often in ways that no human would ever be (screenshots below from Twitter and Bluesky; click on the image to see the originating Tweet):

Some of what’s circulated, Google claims, is faked, but it’s hard to verify because the company appears to have been tracking the funniest/worst viral results and individually removing them. On Thursday, in the evening hours, as MSNBC parents celebrated their 34-0 victory over Donald Trump, Google released a statement letting everyone know that, actually, everyone loves AI Overviews, and they’re here to stay:

User feedback shows that with AI Overviews, people have higher satisfaction with their search results, and they’re asking longer, more complex questions that they know Google can now help with. They use AI Overviews as a jumping off point to visit web content, and we see that the clicks to webpages are higher quality — people are more likely to stay on that page, because we’ve done a better job of finding the right info and helpful webpages for them.

There’s not much to go on from this statement, except that the product is apparently successful by Google’s own metrics, if not by mine. But what worries (and interests) me about AI Overview is not so much whether it’s popular or not (or even whether not it “works” more often than not), but what it tells us about how Google understands its own product and business.

How do Google search results work?

One particularly fascinating aspect of the AI Overview fiasco is the manner of its failure. Maybe the greatest of the AI Overview errors was the cheerful suggestion to “add 1/8 a cup of non-toxic glue to [pizza] sauce to give it more tackiness,”1 which appears to come from a decade-old joke comment by someone called “Fucksmith” located deep in a Reddit thread somewhere.

In other words, the AI Overview errors aren’t the familiar hallucinations that open-ended large language models like ChatGPT will produce as a matter of course, but something like their opposite. If hallucinations are plausible falsehoods--statements that sound correct but have no grounding in reality--these are implausible “facts”--statements that are facially untrue but have direct textual grounding. Unlike the responses produced by ChatGPT, every string of text in an AI Overview has a specific (and often a cited) source that the model is dutifully summarizing and synthesizing, as it has been directed to do by its prompting. It’s just that, well, sometimes the source is Fucksmith.

In its statement, Google is eager make clear that the AI Overviews don’t “hallucinate,” but I’m not sure this is entirely flattering to Google. What it suggests is that Google’s problem here is not so much a misunderstanding of what LLMs are good at and what they’re for, but--more troublingly--a misunderstanding of what Google is good at and what it’s for. Deploying the AI Overview model to recapitulate a set of specific and narrowly selected texts--that is, the search results--strikes me as a relatively legitimate and logical use of a large language model, insofar as it takes advantage of the technology’s strengths (synthesizing and summarizing information) and minimizes its weaknesses (making bullshit up all the time).2 The LLM is even doing a pretty good job at creating a syntactically coherent summary of the top results--it’s just that “the top results” for any given search string often don’t represent a coherent body of text that can be sensibly synthesized--nor, as Mike Caulfield explains in an excellent post on why this style of synthetic “overview” drawn from Google results is poorly adapted to the task of search, should they:

a good search result for an ambiguous query will often be a bit of a buffet, pulling a mix of search results from different topical domains. When I say, for example, “why do people like pancakes but hate waffles” I’m going to get two sorts of results. First, I’ll get a long string of conversations where the internet debates the virtues of pancakes vs. waffles. Second, I’ll get links and discussion about a famous Twitter post about the the hopelessness of conversation on Twitter […] For an ambiguous query, this is a good result set. If you see a bit of each in the first 10 blue links you can choose your own adventure here. It’s hard for Google to know what matches your intent, but it’s trivially easy for you to spot things that match your intent. In fact, the wider apart the nature of the items, the easier it is to spot the context that applies to you. So a good result set will have a majority of results for what you’re probably asking and a couple results for things you might be asking, and you get to choose your path.

Likewise, when you put in terms about cheese sliding off pizza, Google could restrict the returned results to recipe sites, advice which would be relatively glue-free. But maybe you want advice, or maybe you want to see discussion. Maybe you want to see jokes. Maybe you are looking for a very specific post you read, and not looking to solve an issue at all, in which case you just want relevance completely determined by closeness of word match. Maybe you’re looking for a movie scene you remember about cheese sliding off pizza.

You cannot combine this intentionally diverse array of results into a single coherent “answer,” and, it’s worth saying again, this is a strength of the Google search product. It is possible I am in a minority here, but speaking for myself I want to see a selection of different possible results and use the brain my ancestors spent hundreds of millions of years evolving to determine the context, tone, and intent.

LLMs vs. Platforms

Google’s response to complaints about AI Overview errors has been to dismiss the examples as “uncommon queries.” That’s probably true, not just in the specific (it is uncommon to Google “how many rocks should I eat”) but in the general sense that most Google searches are essentially navigational (i.e., looking for a specific official website you want to visit) or for pretty straightforward factual questions like “what time is the Super Bowl,” where a user probably doesn’t actually want or need domain diversity in their results. But the addition of the AI Overview module at the top of the results isn’t merely a problem in the case of those “uncommon queries” where it produces implausible “facts” based on shitposts. It’s a problem everywhere, because it fundamentally changes what Google presents itself as.

As Henry Farrell points out, “new” A.I. Google is held responsible for its output in a way that “old” Google never would have been:

On the other, when Google Original Flavor clearly gets things wrong, it isn’t on the hook. It is not itself asseverating** to the correctness of the sources that it links - instead it is merely indexing the knowledge provided by other people, for whom Google itself takes no responsibility.

That sweet deal is not available to New Google. The new approach isn’t just linking to other people’s stuff. It’s presenting what appears, to ordinary users, to be Google’s own summarization of the best state of knowledge on a particular topic. People may still often continue to treat this as inerrant. But when there are obvious, ridiculous mistakes, they are likely to treat Google as directly responsible for these mistakes. Google has, effectively, put its own name to them.

Farrell doesn’t use the p-word, but if this sounds familiar it’s because what he’s describing is a basic tension of the platform, the business model that has come to dominate both the 21st century software industry and the ordinary experience of the internet. Platforms are businesses that make their money by connecting various kinds of users or customers in a mutually beneficial network--buyers to sellers, consumers to advertisers, horny people to OnlyFans models, grandparents to Uzbeki guys making A.I. images of Jesus made out of shrimp. In order to function smoothly, they need to maintain a set of convenient and widely believed legal and cultural fictions: that they are fair, neutral, and, maybe most importantly of all, that neither the platforms as corporations nor any of the specific people who work for them are liable or accountable for the kinds of things you find on them. Google’s business rests to a large extent on the company’s ability to present itself as, as Farrell puts it, “merely indexing the knowledge provided by other people, for whom Google itself takes no responsibility.”

Historically, “A.I.” and “machine learning” and “algorithms” have served as valuable rhetorical tools in maintaining this fantasy of neutrality and non-accountability. The order in which posts or products or search results or A.I. slop images of an African child carving a wooden bust of Vladimir Putin are sorted can easily be attributed to (or blamed on) the obscure and un-accountable decisions of a computer system, never mind that the system was designed and implemented and continuously maintained by a set of human beings making specific judgments throughout the process. One way of thinking about LLMs is as the apotheosis of this strategy: a particularly sophisticated and powerful way to make and enforce value judgments while avoiding any kind of personal or corporate liability or accountability thanks to the mysterious and unanswerable nature of the technology.

And yet… this LLM doesn’t really seem to have worked that way at all? Presumably the impetus for the “AI Overview” was to use LLMs to improve the search experience3 while still being able to hide behind the magickal-rational decision-making of the machine. But as Farrell points out, rather than shift responsibility for the content away from Google, the AI Overviews have the effect of assigning that responsibility to Google--the precise thing “A.I.” is supposed to avoid.

To some extent, this is down to the specific implementation of the Overviews; as Caulfield writes, a better design might lean “further into the summary as being a summary of results — describing what’s in the result set, complete with nods to sourcing, rather than trying to turn results answering vastly different questions into a single answer.” Perhaps there is a differently designed and prompted version that allows Google to retain its pretense of fairness and non-culpability.

But I think there are certain things about the way LLMs work in this context that insist upon responsibility in a way that platform marketplaces don’t--in particular the replacement of an array of third-party choices (however flawed the sorting of that array might be) with a single string of synthesized text. I made fun of Tyler Cowen when he suggested that generative A.I. would obviate social media by summarizing your entire feed, but I think even if his prediction was off-base he was right to sense that LLMs might actually work against platforms rather than for them, and not just because their all-too-human inability to discern tone, context, and intent leaves them vulnerable to reproducing implausible facts. It seems possible chatbots and other text-generating LLMs are, for lack of a better word, ideologically incompatible with platforms as they’re currently conceived.

Structurally speaking, platforms are marketplaces. They’re built around the appearance of transparency and the illusion of choice, and participants generally play along with these fictions even if the truth is somewhat more complicated. LLMs--in particular when instantiated as chatbots--as decidedly not marketplaces. There are no other groups into which the LLM has brought you into contact for mutually beneficial exchange. There is not even the veneer of transparency or choice: The workings of the LLM are constitutively opaque and what you are given is not a scroll of posts or search results to pick from but a single-source, semi-regurgitated synthesis to be treated as mystically authoritative.

After two decades of having their lives mediated by volatile and disappointing platforms, people may be clamoring for a new kind of mediation--knowledge obtained not via neoliberal software marketplace but from the mouth of the occult computer prophet-god. For all my misgivings about platforms, I am not personally ready to make that leap. I was happy when Google was just a list of results, and my general preference would be to make it again as close to a list of results as possible. It’s not that I think the “AI Overview” results can never be helpful or accurate, or that LLMs in general are junk outside of this context. It’s that Google and other platforms play a particular role in the web ecosystem, and shifting away from an even nominally transparent model to an increasingly obfuscated one is movement in the wrong direction.

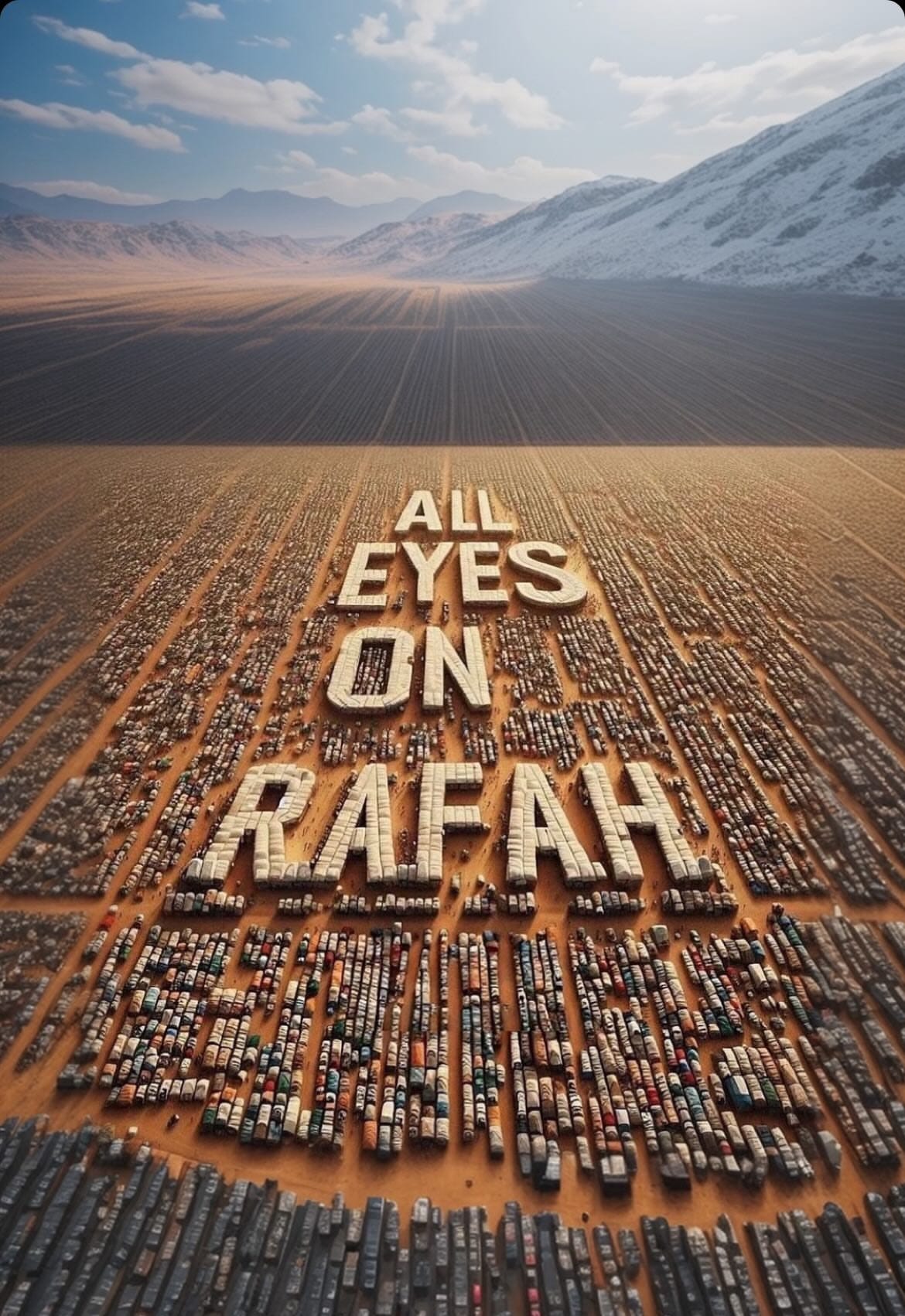

“All Eyes on Rafah”

If you’re on Instagram you almost certainly saw the following viral image this week, created by a Malaysian artist with the handle “shahv4012” after an unconscionable Israeli strike on displaced-persons camps in Rafah killed 45 people:

For S.E.O. reasons (i.e., the people googling “all eyes on Rafah” after seeing it somewhere in their Instagram stories) thousands of news articles have already been written about the image, as well as a certain amount of familiar grumbling about the banalities and inadequacies of social-media activism. Wrapped up in that political frustration was, at least for some people, I think, a bit of aesthetic frustration: Why did this image--well-intentioned but banal, ugly, obviously A.I.-generated--go viral, and not one of the thousands of harrowing and unforgettable photographs of Palestinian civilian suffering that photographers have risked their lives to take since last October? I generally agree with Rebecca Jennings’ assessment at Vox here, which identifies at least four reasons for this particular image’s viral success:

It’s frictionless: The image was created and shared with a built-in sharing sticker that allows it to be easily added to one’s own stories after viewing it.

It’s unmoderated: The image isn’t graphic or upsetting or explicitly political, and is unlikely to be throttled or removed by Instagram’s automatic moderation.

It’s inoffensive (or should be): The message is a relatively anodyne and non-committal call to bear witness and raise awareness, which is the dominant political mode on social media and one people feel the most comfortable with.

All of this sounds basically correct to me, but I want to offer a fourth factor in the image’s success, which is that the image went viral because it’s A.I.-generated. I don’t necessarily mean that people are consciously choosing to share it because of its A.I.-ness, but that the aesthetic qualities it shares with this whole generation of A.I. images--the monstrous scale, the strange emptiness, the eerie precision, the uncanny-valley sheen--give it a little frisson or kick that a well-designed text overlay never could. It’s strange, even ugly, in a way that demands slightly more attention, and ultimately resolves in more sharing. “Being slightly off in a way that demands attention is a good engagement strategy” is a common refrain around here, and even if it wasn’t shahv4012’s intent, I suspect it’s the dynamic behind a lot of A.I.-image success.

Is WhatsApp the most dangerous app of them all?

Over the last decade or so we’ve heard a lot about the threats posed to democracy by Facebook and Twitter and their peers, which are often criticized as vectors for “platforming” extremists, spreading mis- and disinformation, and generally cultivating a culture of fear and mistrust.

I’m not a fan of any of these platforms, even if I don’t endorse every single item in the litany of elite complaint against them, but if I had to choose an actual Worst App That Is Doing the Most Harm to the World right now, I think I would look past TikTok and Facebook and pick out an app that is genuinely connecting extremists to pliable audiences, circulating dangerous misinformation to vulnerable groups, and fostering an atmosphere of cynicism and paranoia among the naive and susceptible: WhatsApp.

A WhatsApp chat started by some wealthy Americans after the Oct. 7 Hamas attack reveals their focus on Mayor Eric Adams and their work to shape U.S. opinion of the Gaza war. […]

Business executives including Kind snack company founder Daniel Lubetzky, hedge fund manager Daniel Loeb, billionaire Len Blavatnik and real estate investor Joseph Sitt held a Zoom video call on April 26 with Mayor Eric Adams (D), about a week after the mayor first sent New York police to Columbia’s campus, a log of chat messages shows. During the call, some attendees discussed making political donations to Adams, as well as how the chat group’s members could pressure Columbia’s president and trustees to permit the mayor to send police to the campus to handle protesters, according to chat messages summarizing the conversation. […]

The messages describing the call with Adams were among thousands logged in a WhatsApp chat among some of the nation’s most prominent business leaders and financiers, including former Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz, Dell founder and CEO Michael Dell, hedge fund manager Bill Ackman and Joshua Kushner, founder of Thrive Capital and brother of Jared Kushner, former president Donald Trump’s son-in-law.

I’ve been reading excerpts from a private WhatsApp group chat established last December by Erik Prince, the founder of the military contractor Blackwater and younger brother of Betsy DeVos, the secretary of education during President Donald Trump’s administration, who invited around 650 of his contacts in the United States and around the world to join. Prince, who has a long track record of financing conservative candidates and causes and extensive ties to right-wing regimes around the world, named the group—which currently has around 400 members—“Off Leash,” the same name as the new podcast that he’d launched the month before.

Among the group’s hottest topics:

• The “Biden Regime,” which a consensus of Off Leash participants who weighed in view as an ally of Islamic terrorists and other anti-American forces that needs to be crushed along with them and its partners in the deep state, such as former Joint Chiefs of Staff Chairman Mark Milley, who “deserves to burn in hell,” Lara Logan shared with the group chat.

• The shortcomings of democracy that invariably resulted from extending the franchise to ordinary citizens, who are easily manipulated by Marxists and populists. “The West is at best a beautiful cemetery,” lamented Sven von Storch, whose aristocratic German family fled the country after World War II to Chile, where their son was raised before returning to the land of his ancestors, where he married the granddaughter of the Third Reich’s last de facto head of state, who was convicted at Nuremberg.

Say what you will about Facebook and Twitter, but the (limited, inadequate) mass political education and organization that take place on those apps is public and transparent. On WhatsApp, right-wing extremists and vulnerable billionaires can coordinate and network in secret, undermining and damaging liberal democracy and the rule of law thanks to this dangerous technology.

If you’re wondering how adding a small amount of Elmer’s to your pizza will turn out, Friend of Read Max Katie Notopoulos went and did it, demonstrating if nothing else that A.I. may in fact have a positive effect on journalism and media jobs.

I’m setting aside here for the sake of argument my belief that the real value proposition of LLMs to most users is the feeling that you’re talking to a super-intelligent computer, elaborated below, which you don’t get from the Google AI overviews.

For one set of marketplace participants, at any rate--the introduction of even a fully working “overview” would not represent an improved experience for publishers that rely on traffic.

![Screenshot of Google search with new AI overview feature.

[ Google Q_ which us president went t..] Thirteen US presidents have attended UW-

Madison, earning 59 degrees in total. Some of these presidents include: e Andrew Jackson: Graduated in 2005 e William Harrison: Graduated in 1953 and 1974 e JohnTyler: Graduated in 1958 and 1969 e Andrew Johnson: Earned 14 degrees, including classes of 1947, 1965, 1985, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2006, 2007, 2010, 2011, and 2012 e James Buchanan: Graduated in 1943, 2004, and 2013 e Harry Truman: Graduated in 1933 e John Kennedy: Graduated in 1930, 1948, 1962, 1971, 1992, and 1993 e Gerald Ford: Graduated in 1975 ( ~ Screenshot of Google search with new AI overview feature.

[ Google Q_ which us president went t..] Thirteen US presidents have attended UW-

Madison, earning 59 degrees in total. Some of these presidents include: e Andrew Jackson: Graduated in 2005 e William Harrison: Graduated in 1953 and 1974 e JohnTyler: Graduated in 1958 and 1969 e Andrew Johnson: Earned 14 degrees, including classes of 1947, 1965, 1985, 1996, 1998, 2000, 2006, 2007, 2010, 2011, and 2012 e James Buchanan: Graduated in 1943, 2004, and 2013 e Harry Truman: Graduated in 1933 e John Kennedy: Graduated in 1930, 1948, 1962, 1971, 1992, and 1993 e Gerald Ford: Graduated in 1975 ( ~](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!8GMr!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F5ee32082-4ae1-4aa5-b5d3-723fe6caa092_1080x1928.jpeg)

"What it suggests is that Google’s problem here is not so much a misunderstanding of what LLMs are good at and what they’re for, but--more troublingly--a misunderstanding of what Google is good at and what it’s for."

Yes, yes, and yes. I've been working with web analytics and SEO for a long time, and while most people click on the top answer on the page without thinking about it because we have trained them Google is always right, many others prefer the list of links. Thank you for articulating the "I prefer a list of links" point of view because most people in search, publishing, and marketing think that if you're not at position 1, all is lost forever. But the data says plenty of people click on the archival links, and often.

It also seems that Pichai/Raghavan's vision of Google is starkly different from Page/Brin's vision, in that they are executives looking to make more money, versus idealistic grad students trying to change the world with the product they built. Not that Page and Brin aren't profit-motivated dopes, but with the company's most recent responses insisting that audiences are wrong in pointing out AI-overview errors, I don't think Pichai is fully on board with Don't Be Evil.

That's what struck me from Zitron's piece a couple of weeks ago: why was Raghavan panicked about getting more clicks in 2019? Google consistently has an 80-90% global market share. Does any other company have an 80% global market share of anything? (that is an honest question) But they are trying to get more money-making clicks because their research product doesn't make enough money somehow.

I don't know Google is making significant edits to their existing wildly popular and profitable research product except to seem cool and relevant for all the SV investors and colleagues who went gaga over ChatGPT. And there are likely business reasons that I don't understand. Because the tech industry is obsessed with going up and to the right forever and monetizing every incremental opportunity instead of building stable products for smart audiences.

One thing worth calling out regarding Google's AI answers is how it represents a massive shift in their business strategy.

As a platform, Google connected people who wanted stuff from the internet (answers, whatever) with people who had that stuff, and they skimmed a bit off the top via sponsored results.

Implicit in AI answers is a desire to keep people on Google itself. They no longer want their users to click through to that link to Reddit, or whatever. They have a bunch of users, and they want to keep them there. In that sense they're now behaving much more like a social media company: Facebook, Twitter, etc, which of course are notoriously hostile to external links. But if the underlying ethos becomes keeping users on google.com, then the value of sponsored results would seem to diminish in value. Why would I the advertiser pay for a link that you are actively trying to keep people from following?