Why do we use social media?

Plus: whatever happened to the "intellectual dark web"?

Greetings from Read Max HQ! In this week’s newsletter:

Examining Jon Haidt and Tyler Cowen’s conversation about social media, and whether or not A.I. will reduce screen time;

a follow-up to last week’s post on “Substackism” with an eye to the “intellectual dark web.”

Another reminder: Read Max (and, basically, my whole life) is funded entirely out of the pockets of paying subscribers. I don’t take advertisements or sponsorships; my freelance income is pretty limited. Subscription is about the price of one beer or one coffee, or, like, one sorta cheap sandwich (?) a month; if any of the 150 or so weekly emails I’ve written over the past two years have made you smile or laugh or do the Wee-Bey GIF thing, please consider signing up. Subscribers get access to the whole archive; the weekly roundup of book, movie, and music recommendations (usually another 2,000 or so words of writing); and the sense of accomplishment and satisfaction that comes with supporting writing that doesn’t make you want to die.

Why do we use social media?

Jonathan Haidt has a new book out called The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness. If you haven’t heard of him, Haidt is “the Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at the New York University Stern School of Business,” which is not the sort of thing of which I had ever realized one could be a professor, but his fame really rests on being a kind of sober academic critic of campus politics, especially in his previous book, The Coddling of the American Mind, which I will never, ever, in my life, read. Haidt is not the absolute worst kind of airport-book business-school social psychologist, as these kinds of guys tend to go, but I don’t think he’s very smart and he is not someone whose intuitions I particularly trust, even if I agree in a loose sense with his new book’s thesis that phones are bad.

Recently, Haidt was a guest on the charmingly maniacal libertarian economist Tyler Cowen’s podcast. Cowen (who I once spoke to for a podcast I did with New York magazine called 2038) is generally a “techno-optimist” and natural skeptic of the “phones bad” narrative. The two men had what I thought was a revealing exchange “on whether AI can solve the screen time problem.” I’m going to quote a fairly lengthy chunk, sorry in advance:

COWEN: You’re worried about screen time. Why isn’t it the case that AI quite soon is simply going to solve this problem? That is, you’ll have your AI agent read the internet for you, or your messages or whatever, and if you want it to talk to you or give you images or digest it all, isn’t it going to cut down on screen time immensely? […] Screen time seems super inefficient. You spend all this time — why not just deal with the digest? Maybe in two, three years, AI cuts your screen time by 2X or 3X. Why is that so implausible?

HAIDT: Well, Tyler, you’re talking as an intellectual who has probably the highest reading throughput rate of any human being I’ve ever heard of. For you, you’re looking at this like, “All this information coming in from screens, we could make it better.” I’m sure you’re right about that.

I’m thinking about children, children who desperately need to spend hours and hours each day with other kids, unsupervised, planning games, enforcing rules, getting in fights, getting out. That’s what you need to do.

Instead, what’s coming — it’s already the case for boys especially, that they can’t go over to each other’s houses after school because then they can’t play video games. When you and I were young, video games were coming in, and you’d go over to someone’s house, and you’d sit next to each other, and you’d play Pong or whatever. You’d play a game, and you’d joke with each other, and you’d eat food, and then you’d do something else.

Video games used to be fairly healthy, but once they became multiplayer, you wear your headphones, you’ve got your controller, they’re incredibly immersive. Now, you have to be alone in your room in order to play them. Now, you bring in virtual AI girlfriends and boyfriends. Already, Gen Z — those born after 1995 — are completely starved of the kinds of social experiences that they need to grow up.

In theory, I’m sure you’re going to say, “Well, why can’t we just train an AI friend to be like a real friend and get in fights with you sometimes?” Maybe in theory that’s possible, but that’s not what it’s going to be. It’s going to be market-driven. It’s going to be friends and lovers who are incredibly great for you. You never have to adjust to them. You never have to learn how to deal with difficult people, and it’s going to be a complete disaster for human development.

COWEN: Complete disaster strikes me as too strong a term for something that hasn’t happened yet. I think you’re much too confident about that.

HAIDT: What do you mean it hasn’t happened yet? […]

COWEN: If screen time is making kids so miserable, why won’t they use new AI innovations to lessen their screen time? If they don’t want to stare at the screen, turn messages into voice through earbuds, turn it into images, whatever makes them happier. Why are they so failing to maximize?

HAIDT: Because — and this is one of the key ideas in the book — what I think makes it different is that I’m a social psychologist with a lot of interest in sociology. I like to think systemically. Over and over again, what you see when you look at this problem is collective action problems.

I teach a class at NYU, and my students spend enormous amounts of time on TikTok and Instagram. Many of them spend four, five, even six hours a day consuming content from just these two or three sites. Why don’t you just quit? Because they say it blocks out everything else. They don’t have time to do their homework. Well, why don’t you just quit? They all say the same thing. “Well, I can’t because everyone else is on it, because then I’ll be left out. I won’t know what people are talking about.”

So, Haidt’s argument is something like, unstructured social time is extremely important for human development, and screens gets in the way of this social time, but young people feel obligated to attend to their screens because of social pressure to keep up with what’s happening.

And Cowen’s argument is something like, don’t worry because A.I. will someday create digests of activity on social media and messaging apps, which will allow people to more efficiently consume “what’s happening.”

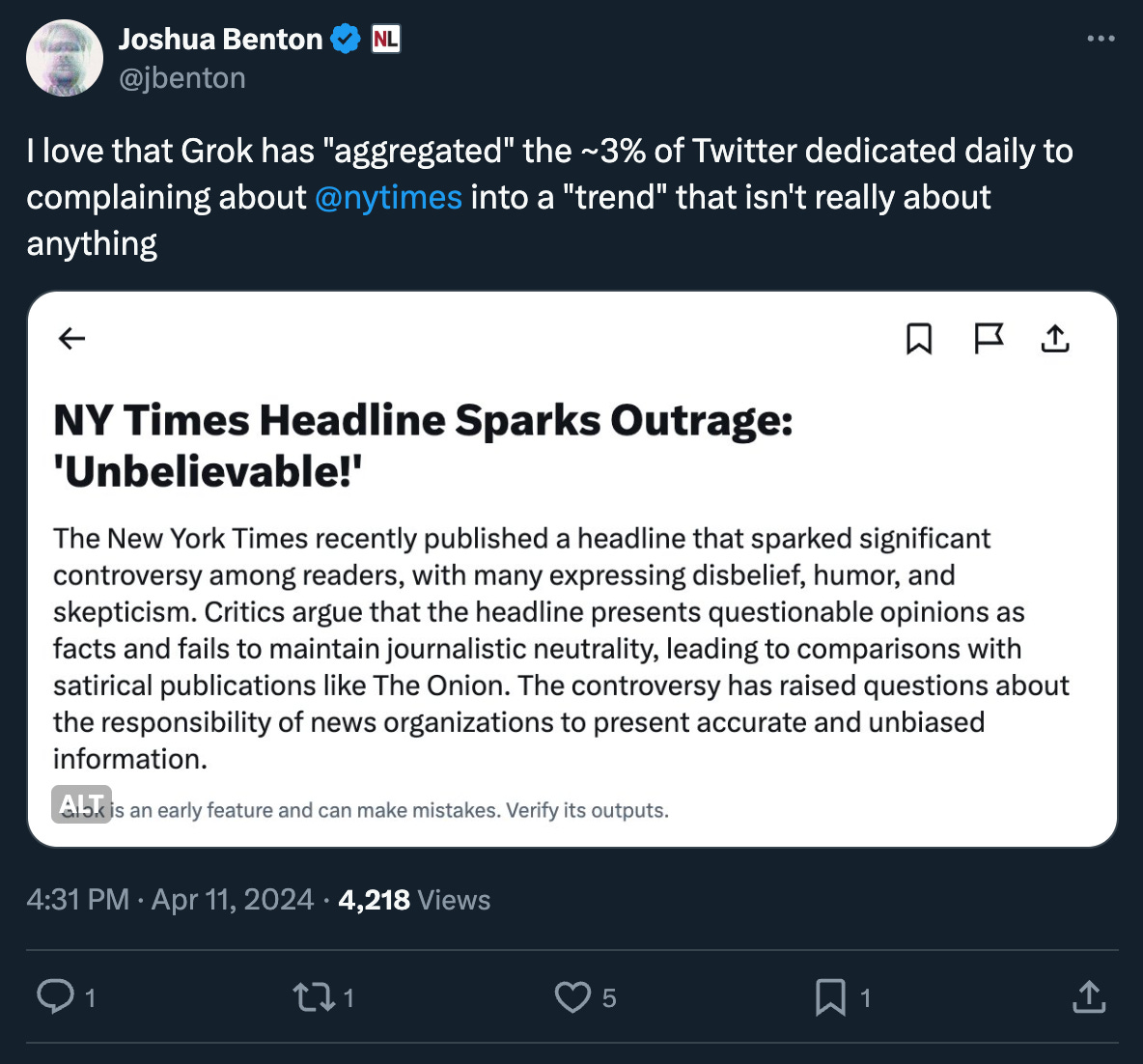

For whatever it’s worth, Cowen’s argument here is so patently insane that not even commenters on his blog, home to one of the most insane comment sections on the normal internet, are buying it. For starters it requires you to believe that A.I. will soon (or ever) be able to convincingly, accurately, and satisfyingly summarize the mass of complexly meaningful and context-dependent text (not to mention video) that makes up “the internet,” which is not necessarily an impossible task but I think one that is harder than Cowen allows. I thought of his idea of A.I. digests several times this week while reading summaries of Twitter written by the company’s built-in A.I. “Grok”:

Obviously, there are better A.I. summarization tools out there than “the one Elon Musk is in charge of,” but early results are not promising.

That being said, the problem here is not so much Cowen’s not-yet-earned faith in the ability of large language models to detect and deploy irony. It’s that both Cowen and Haidt seem to agree on a frankly bizarre account of why people use social media: mainly and merely for consuming information. If you take Haidt’s account of his students’ account of why they spend so much time on TikTok and Instagram at face value--“Well, I can’t because everyone else is on it, because then I’ll be left out. I won’t know what people are talking about”--it follows relatively cogently that A.I. summaries of whichever psychotic and probably fake Zoomer dating TikToks are currently doing the rounds would allow them stay in the loop and free up plenty of time for young people to devote to unstructured play and Ethical Leadership 101 or whatever.

But (and no disrespect to the lived experience of Haidt’s anecdotal students) “staying in the loop” and “consuming information” are, at best, tertiary reasons for using social media. What about, you know, the social? If information was the point, you could just read plain old media; what makes TikTok and Instagram and whatever else special is the sociality. Where does that appear in Cowen and Haidt’s model? Cowen can be excused for misapprehending human behavior and motivations on account of being a George Mason University economist. Haidt, for his part, has backed himself into a corner. He seemingly can’t allow for the possibility that there might be a compelling sociality to any part of screen time, because by his framework screen time is always and forever non- or anti-social.1

And yet… and yet! Just because screen time is more social than Haidt wants to admit doesn’t necessarily make that (structured, mediated) sociality the point, any more than the fact that social media can be a source of information make the information (and the inefficient production/consumption thereof) the point. As everyone who’s had pain in their thumb from scrolling knows, the actual point of “screen time” is the time part--the hours it allows you to numbly burn up. There’s no “more efficient” version of social media because you can’t pass time any more quickly. I still haven’t found a better account of the lure of screen time than Richard Seymour’s book The Twittering Machine, which deploys Natasha Dow Schüll’s concept of the “machine zone,” first articulated by the video-slots addicts she studied, as a framework for thinking about social-media “addiction”:

Schüll calls it the ‘machine zone’ where ordinary reality is ‘suspended in the mechanical rhythm of a repeating process’. For many addicts, the idea of facing the normal flow of time is unbearably depressing. […] What we do on the Twittering Machine has as much to do with what we’re avoiding as what we find when we log in – which, after all, is often not that exciting. There is no need to block out the windows because that is what the screen is already doing: screening out daylight. […] this horror story is only possible in a society that is busily producing horrors. We are only up for addiction to mood-altering devices because our emotions seem to need managing, if not bludgeoning by relentless stimulus. We are only happy to drop into the dead-zone trance because of whatever is disappointing in the world of the living. Twitter toxicity is only endurable because it seems less worse than the alternatives.

To be fair to Haidt, I think he’s alive to the chronophagic aspects of social media, which he dully describes in the Cowen interview as “opportunity cost.” But based on the reviews I’ve read, his book seems intently (and perhaps unrigorously) concerned with establishing social-media use as the specific cause of depression and mental illness among young people. It seems more productive, and more realistic, to imagine screen time as a symptom of those problems, and many others--a compounding symptom, maybe, but a symptom nonetheless.

What comes after the Intellectual Dark Web?

I was a little annoyed this week to come across Cathy Young’s Bulwark essay about the afterlife of the Intellectual Dark Web--not because the piece is bad but because it would have served as a good peg for my newsletter last week about the political project of the conservative Substack publication The Free Press, founded by former New York Times editor Bari Weiss. Young does a quick “where are they now” of the figures photographed for the original “Intellectual Dark Web” feature in the Times (written by Weiss), and finds that most of them are … cranks:

Of the IDW stars profiled in Weiss’s article, several—former Evergreen State College biology professors Bret Weinstein and Heather Heying, a married couple; Canadian psychologist and bestselling guru Jordan Peterson; podcaster Joe Rogan—have devolved into full-blown cranks. In a recent podcast episode, Peterson goes full Alex Jones on COVID-19 vaccines, claiming they caused more deaths than the “so-called pandemic,” and barking his skepticism about childhood vaccination in general. Weinstein and Rogan recently used Rogan’s podcast, which has an audience of millions, to push not only the notion that mRNA vaccines, including the COVID-19 ones, are lethally dangerous but the idea that HIV isn’t the real cause of AIDS and that HIV-skeptical maverick scientist Kary Mullis’s death in 2019 may have been engineered by Dr. Anthony Fauci. The ranks of the cranks also include author and podcaster Maajid Nawaz, briefly mentioned in the original IDW piece as a “former Islamist turned anti-extremist activist”—now a vaccine and 2020 election conspiracy theorist, and most recently seen boosting the Kremlin’s efforts to link Ukraine to the ISIS terror attack in Moscow.

I would object to this only to say that all of these people were already plainly cranks in 2018, but Young’s point is well-taken either way: The “IDW” has openly split into something like “left” and “right” factions, where the left-IDW is ideologically aligned with the never-Trump center-right and the right-IDW thinks the prime minister of Canada is secretly gay. Young keys in on the now awkward place of Weiss, the packaging genius who tried to cohere the IDW in the first place and is now running a popular publication that’s attempting to straddle this widening schism:

The bottom line is that the site sometimes stumbles into the same pitfalls about which Weiss warned the IDW, including the embrace of “grifters”: Last August, Weiss conducted a spirited but respectful interview with then–presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy, the guy who not only thinks that Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelensky are “two thugs” vying for turf in Eastern Europe but has repeatedly suggested that January 6th was an “inside job” and flirted with 9/11 “trutherism.” Obviously, a presidential candidate, even one with no chance of winning, is a legitimate subject for an interview. But Weiss treated Ramaswamy as an interesting and fresh voice on the political scene—and, despite some pushback on the Ukraine issue, did not delve into his more extreme statements. That’s not just an interview, it’s validation—and misleading validation at that.

Young identifies “audience capture” as one of the factors the Free Press’ continuing openness to right-IDWism, and this seems likely to me; the mood of the comment section there suggests that the Substack subscriber audience is more open to various strains of crankdom than your average center-right Republican. But I also think Weiss has a kind of fusionist project in mind--a marriage of the pro-woo to the anti-woke, in service of her own neoconservative politics--that obligates her to keep the Free Press at least somewhat friendly to the right-IDW. And, you know, she may be right: The Bulwark, the anti-Trump, center-right, elite-conservative publication for which Young wrote this essay, has half as many subscribers as the Free Press.

This is what leads him to make absurd claims like playing multi-player video games online means “you never have to learn how to deal with difficult people.” Buddy--multi-player online video games are the Ivy League of learning how to deal with difficult people.

How about social media is designed to be addictive to maximize scroll time and ad revenue? It’s just capitalism, y’all.

Yes, the idea of “AI digests” misses the point, but even more fundamentally: there’s no profit motive to reduce screen time.

"... what makes TikTok and Instagram and whatever else special is the sociality."

Here is where I think your thinking goes wrong. You're taking the "social" part of social media literally, without interrogating it. "Parasocial" was a term that was popular there for a minute, and I think that's a much better descriptor for what Tiktok and Instagram actually are.