Greetings from Read Max HQ! In this week’s edition, a long-ish column on the new Alex Garland film Civil War. Vague but significant spoilers follow; I’m not sure they matter for one’s enjoyment (if that’s the right word) of the movie, but be aware.

A brief reminder: Read Max is funded entirely by paid subscriptions. I’m able to take the time and energy to produce two editions a week about whatever is on my mind--tech, media, politics, the 1992 direct-to-video movie Nemesis, and whatever else, because of support from readers who find my writing, for whatever reason, valuable. If you like Read Max--if you get roughly one (1) Big Mac’s worth of value from it a month--please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

And, if you like this newsletter, please share it with friends, family, enemies, strangers, coworkers (appropriately)--I have no marketing budget and rely on the enthusiastic recommendations of current readers to find new ones!

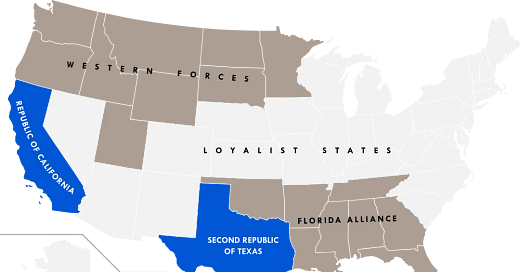

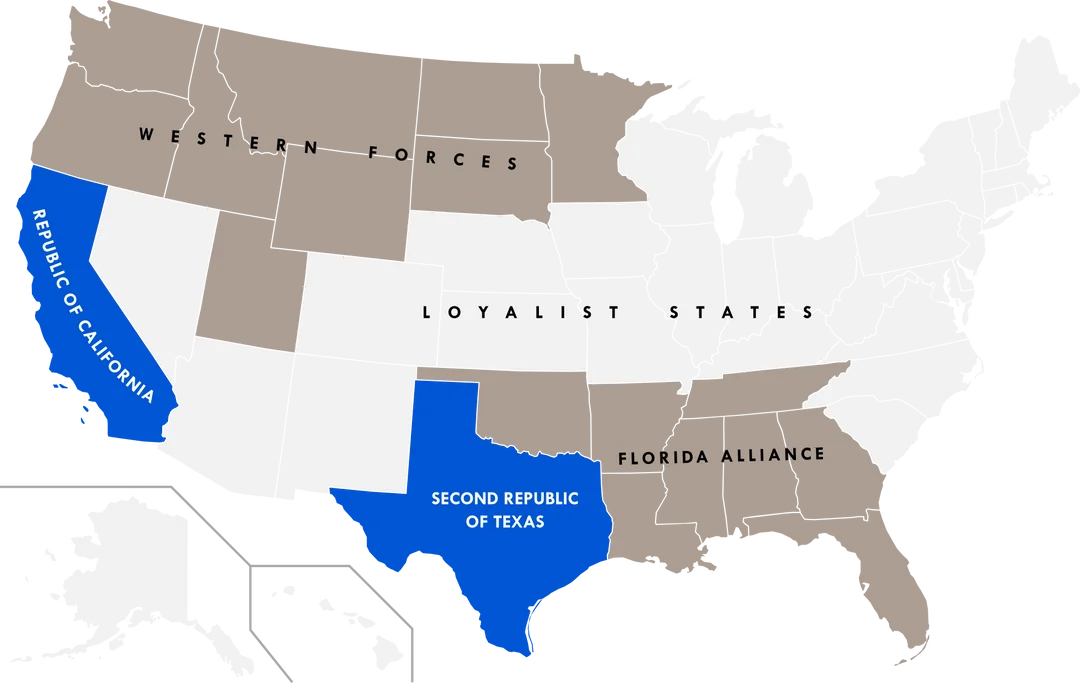

It first became clear that Alex Garland’s new movie Civil War would not be an “explainer movie” back in December, when the trailer was released, and a map that briefly appears therein was painstakingly reconstructed by a Redditor in r/imaginaryelections.

California and … Texas? Arizona … Nebraska … South Carolina … and New Jersey?

By “explainer movie” I mean the kind of movie about which long and pedantic “explainers” are written--movies with fictional worlds deep and sophisticated enough to support a thriving media economy of explication, analysis, and fan theory on any of the many hubs for culture content produced by and for the over-educated and under-occupied, such as the one you are reading right now. Over the last two decades,1 explainer movies have come to dominate the Hollywood blockbuster production line (not to mention prestige-television development) as producers realize that audiences have a willingness or even an appetite for movies that seem to require some amount of extra-textual homework to fully appreciate them. Think the MCU, or the Star Wars sequels and prequels, or Dune: The worlds of these movies (rather than the movies themselves) are endlessly dissected, theorized, and reconstructed (often semi-ironically) by history and military and policy and trade and economics and elections nerds on Twitter and Reddit, who are often members of or overlap with devoted franchise fandoms, activity both remunerative to publishers (again, to emphasize the self-implication, such as the one you are reading right now!) and platforms, and that serves as earned marketing for the studios.

The map above, created by a Redditor in their free time off a brief glimpse of a TV screen in a short trailer, is precisely the kind of content continuously produced by the explainer-media ecosystem. The expectation that any background detail in an explainer movie will be screencapped and scrutinized has led to a cottage industry in world-building details like fully grammatical constructed languages with their own designed alphabets.

But that map… those alliances… The redditors who reply are, at best, skeptical. (“Okay, we can work with this,” the top comment writes, like someone trying to roll a joint with stems and seeds.) What explainer could possibly justify the historical conjuncture implied by this balance of power? Where was the care and detail in world-building that the explainerists had come to expect? Aimee Walleston points out that the reaction to the map and the idea of a California-Texas alliance essentially accused Garland of “a poor interpretation of the contemporary lore of the United States… Comments like this harkened, for me, the critiques made by authors and consumers of fanfiction… The fictional universe here isn’t Hogwarts or Assassin’s Creed, however, but the contemporary United States, which has now been lore-ified.”

In interviews, Garland himself has seemed mostly disinterested in the idea of “lore,” by which in this case I suppose I mean “history” and “political economy.” “Why are we shutting [conversation] down? Left and right are ideological arguments about how to run a state,” he said at SXSW in March. “That’s all they are. They are not a right or wrong, or good and bad. It’s which do you think has greater efficacy?” Garland seems to understand his film as a kind of message movie about the dangers of partisanship and the importance of journalism. And while I don’t necessarily disagree, “journalists who neutrally portray political conflict are heroes of democracy” is not a message for which I am a particularly eager or compliant audience, especially if it’s coming from someone whose basic theory of this historical conjuncture is “We made [politics] into a moral issue, and it’s fucking idiotic, and incredibly dangerous … I personally [blame] some of this on social media.”

All of which is to say I was not feeling particularly generous when I settled in to watch Civil War this weekend. And yet: I liked it.

The movie follows four war reporters as they road-trip from occupied New York City through a burnt-out mid-Atlantic, headed to Charlottesville, Va., where the Western Forces are planning the final assault on D.C.--with the hopes of sneaking across the front lines to interview the president, or at least photograph him, alive or dead. Kirsten Dunst plays a legendary Reuters war photographer, Wagner Moura her correspondent partner, Stephen McKinley Henderson a Times correspondent hitching a ride, and Cailee Spaeny a young freelance photographer trying to get her big break. As they drive from New York through Pennsylvania, they encounter familiar scenes of war-zone desperation: Desperate battles between strung-out soldiers, local militias lynching accused looters, refugee camps, mass graves. When they finally reach D.C., their number down to three, they embed with a Western Forces unit that blows up the Lincoln Memorial before engaging in a final assault on the White House.

This is the sum total of facts we learn about the world of Civil War from the events of the movie itself:

Texas and California are leading an alliance called “The Western Forces,” which is about to take Washington D.C.

Florida is leading its own secessionist alliance, which the Carolinas may be threatening to join.

Canadian money is worth a lot more than American money now.

The president has droned American citizens and disbanded the F.B.I. sometime in the recent past.

There are or were Maoists in Portland (what else is new).

Twenty or so years prior to the events of the movie there was something called “the Antifa Massacre.” (LOL)

So, yes, that’s not much to go on. The conflict sketched by these details is emphatically not the exhaustive “realistic” product of a war-gaming, politics-knowing, history-nerd Redditor-type, complete with a lengthy bible of extra-textual lore. Nor is it the somewhat more refined, intently contemporary, Kim Stanley Robinson-style future-projection of an “apocalyptic systems thriller.”

I can understand being annoyed by this, and wanting from the movie a firmer grasp of the politics it’s playing around with (in addition to the hilariously, woodenly vague reference to “the Antifa Massacre,” the reporters come across a squad of fighters clad in Hawaiian shirts, a la boogaloo boys) and a clearer sense of how and why the mid-Atlantic descended into hunger and violence. But I think Civil War is coming out of a different tradition than the explainer movie or the political thriller. Its world-building is the kind familiar from an earlier era of Hollywood sci-fi--an expediently vague, geographically improbable, politically nonspecific conflict about which the audience is actively encouraged not to ask questions. And that works in this case because the movie itself is effectively a throwback--a blockbuster with the soul of an exploitation flick, perfect for fans of direct-to-video sci-fi, battered pulp-fiction paperbacks, under-baked and action-forward ‘80s and ‘90s blockbusters, and other speculative-fiction media that has traditionally been not particularly interested in raveling detailed and internally consistent lore.

For Civil War, Garland is clearly drawing some of his images and characterizations from war-reporting classics like The Killing Fields and Salvador (as well as more general war-movie classics like Come and See and Apocalypse Now) but those movies--rooted as they were (mostly) in specific places and real events--evinced clear political or moral obligation. In “making a movie that pulls the polarization out of it,” as he put it, Garland has ended with something more like Twister, but with war instead of tornadoes.2 Yes, the heroes are journalists, but very little of the movie’s runtime--five or six minutes--is consumed with conversations about the ethics of war reporting or encomiums to journalism, and the moral dilemmas hinted at are never actualized by the events of the movie. (Indeed, we never even see how or where the journalist characters, who are mostly portrayed as cruel and ambitious sociopaths and depressives, file their copy or photos?) Yes, it’s about a civil war, but almost none of the movie addresses or indicts, directly or abstractly, the kind of “polarization” condemned by Garland in press interviews, outside of a (allegorical?) scene in which an armed Jesse Plemons asks the characters “What kind of American are you?” As it turns out, he’s not really even asking them what side they’re on; he wants to know which states they’re from.

Of course, if you’re willing to do a lot of fill-in-the-blanks work, you could abstract out from the movie a critique of dehumanizing political rhetoric and its role armed conflict. But precisely because it’s not an explainer movie, there’s no “lore” connecting political conflict in 2024 to the scenes of violence and cruelty. Ultimately the movie seems much less concerned with making a particular political or moral statement (or even exploring the politics or morals of its fictional scenario) than it does with efficiently and energetically moving its truck of adrenaline junkies from one suspenseful action set-piece to the next. It’s like finding a 1967 alternate-history novel published by Del Rey with the tagline “They Crossed a War Zone Between New York and D.C.--to Photograph the President’s Murder!”

That Civil War is essentially a big-budget Tubi classic with great actors might sound more surprising than it should. Garland is among the best working sci-fi writer-directors, but I think his reputation as a “cerebral” filmmaker and his generally tasteful visual style sometimes distract from the fact that his metier is pulp--heightened, plot-driven stories animated by big, broad ideas and provocative narrative turns. Almost all of his work has that wonderfully broad sci-fi paperback quality, packaged in a misleadingly stylish aesthetic: “At a remote retreat, he fell in love… with a robot!” “A deranged scientist… a Russian agent… and a computer… that might be God!” Civil War shows off Garland’s many strengths: a notable ability to generate and sustain tension, an eye for striking fantastical images, and a facility for convincing and directing exceptional actors. But as a piece of cinema it’s mostly animated by a simple and powerful concept for generating compelling images--“what if war, but America.”

None of which is to say that you have to like Civil War. Pulp can be uncomfortably nihilistic. “Exploitation” movies are called that for a reason: they exploit charged ideas and images in service of lurid and thrilling narrative rather than political commitment or moral responsibility. By showing a bombed-out American countryside and vaguely referencing Antifa and the Boogaloo Boys, generating audience tension in a narrative purged of specific politics,3 Civil War flirts with exactly that kind of nihilism, and I don’t blame anyone who isn’t interested in readerly generosity toward a movie that depicts uniformed soldiers summarily executing journalists as a suspenseful set piece.4

But this is partly what I find most fascinating about Civil War. What does it mean to make a film supposedly about polarization and contemporary political conflict that’s itself so shorn of explicit political content? What does it say about the Trump era that its liberal blockbuster cri de coeur is an often-gruesome exploitation flick that ends with the war-crime execution of its Trump analogue?

I mean, there are some obvious answers to reach for.5 But one thing that struck me about Civil War was the way that the movie’s careless mix of contemporary political signifiers absent recognizable political conflict rendered the “sides” vaguely familiar but ultimately unknowable, their dissatisfactions never fully articulated, their lives shallowly mediated for the viewer by careerist, thrill-seeking journalists chasing bigger stories. Put another way, the (American) audience presumably experiences this fictional U.S. civil war in the same it experienced civil wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria--as something between inscrutable tragedy and thrilling entertainment. In practice, the film’s central image-generating conceit ends up being less “what if America had a second Civil War?” and more “what if 2007 Iraq happened in Pennsylvania?”

Where did Trump come from, anyway? How and why did we arrive at this political moment? Still under-appreciated in diagnosing our problems, I think, is the near-unmitigated disaster of 21st-century American foreign policy beginning with the war in Iraq: criminal invasion, catastrophic occupation, hundreds of thousands dead, millions displaced, all in a shockingly brazen violation of public and international trust. The imperial violence cheered on by elite journalists and nominally liberal politicians has now come home, to their sudden consternation. It seems only natural, in this sense, that Garland, in setting out to make a movie about “political polarization,” would come out with a troubled fantasy of American self-occupation. After all, a president willing to drone-strike American citizens isn’t alternate-history lore.

While the simultaneously pedantic and speculative culture of explainer movies has flowered in the internet era, it has an extensive and obvious genealogy going back through Star Trek fandom and the “Sherlockian game” of Sherlock Holmes fans.

Because I’m worried that new readers aren’t necessarily familiar with the Read Max hierarchy of taste, I need to be clear that any comparisons to Twister or mass-market science fiction paperbacks are wholly laudatory.

A defense against this charge might involve arguing, as Jamelle Bouie does, that the movie’s true political commitment is opposition to war. I think this is true, as far as it goes, but I tend to agree with Truffaut about “anti-war” movies that revel in the thrill of their own violence. Either way I wonder if the reception of this movie might have been different if Garland had spent more time on the press tour talking about the horror of war as such than about the dangers of political polarization, since the former is pretty unimpeachable and much more central to the themes of the movie as it exists, while the latter is itself a kind of partisan political concern whose relationship as theme or plot to the movie is pretty tenuous.

Plus, if you believe that Roland Emmerich conjured 9/11 into existence by pre-imagining it across his ‘90s disaster masterpieces, then this movie has impossibly bad juju.

One answer, suggested in this considered negative review by Osita Nwanevu, might be that the centrist liberalism to which Garland seems to subscribe, under which “left” and “right” are merely electoral labels for differing modes of resource distribution, simply doesn’t have the tools to articulate or understand how conflict arises--all it can offer is violent entertainment and grisly, ambivalent wish-fulfillment in the guise of moral hand-wringing.

Haven't seen this movie yet, but based on your review and others I've read, I feel like it teed itself up to have a more humanistic and less internet-culture-war-politics approach to the Civil War 2 scenario -- which is valid -- but then maybe got distracted by action scenes and following protagonists who happen to be there for all the most important events.

I'm reminded of a portion of a WWII documentary I watched on Youtube (World War Two in Real Time -- it's great) about D-Day and how when they were storming the beaches, not every beach was like Saving Private Ryan. They talked about how village commuters were waiting for their bus or having a morning coffee on the boardwalk when all of a sudden Allied troops stormed through. I had never really thought about what it would be like for the average person in occupied France in 1944, but I guess they'd still be drinking coffee and commuting to work, and occasionally encountering soldiers of various stripes who may disrupt/destroy everything or may just be moving through to the next objective.

Also reminded of the scene in the movie Beirut when the taxi driver is explaining to Jon Hamm how they shouldn't take X highway because a car bomb had gone off there that morning. And how the Muslims were blaming the Christians and the Christians were blaming the Israelis and the Israelis were blaming the Muslims. He asks the cab driver what he thinks and he responds "I think we shouldn't take X highway".

So perhaps the average person wouldn't really have a good idea of what's going on or what the backstories are of each of the factions and why they are fighting. But then by following journalists instead of "civilians" the protagonists will naturally follow the action and be more clued in to what's going on than the average person actually would. So then the fact that we the audience /still/ don't know what the civil war is actually about is maybe an indictment of journalism rather than a lionization of it? That decontextualized violence gets views and explaining why they're doing it might offend people so it's better to just maintain the view from nowhere.

....hmm I liked the under-explaining. I thought the politics of the movie was that liberals are coming for Trump and as far as you could tell they have no choice but what have we become, a civl war degrades both sides etc.? It seems less preachy because it stays vague.

The images had power and (cinematic) plausibility because we've seen them in reporting on the rest of the world so what if the circumstances that make war-reporting possible in Serbia or Libya happened here? They take that premise and work backwards, not filling in too many blanks. Mixing the "war zone" cinema style with the "protect the president with badass technology like The Beast" cinema style, where the symbols of presidential power become like the Fürherbunker, was particularly effective.

Where the not making sense was a problem for me: what do the journalists think they are up to? Who do they work for, who reads their stories and looks at their photos? In American journalism movies the American People need to know whatever the journalist is reporting so they can Act. Also the grizzled war correspondent who vaguely evokes Hilary Clinton teaching the inexperienced Gen Z mentee seemed odd, if Cailee Spaeny grew up during the Civil War you'd assume she's seen a lot.