What is "Substackism" and where does wellness fit in?

Plus: a genealogy of the "apocalyptic systems thriller"

Greetings from Read Max HQ! In today’s newsletter, two items:

The burgeoning Substackist ideology and the place of woo and alternative wellness inside it;

the genealogy of the “Apocalyptic Systems Thriller” and a call for recommendations.

A reminder: Read Max is my sole source of income and is supported almost entirely by the still somewhat confusing generosity of paying subscribers. (I say almost because I made about $100 off of affiliate links last year… hell yeah.) If you read this newsletter every week, or even most weeks, and find it informative or entertaining or thought-provoking or simply “didn’t make me want to die,” consider becoming a paid subscriber for about the price of one (1) beer or foamed-milk coffee drink a month:

Finally, please note that I may receive a small commission if you purchase books via links in this email.

Health news in the age of New Vitalism

The Free Press, the Substack-based publication founded by former New York Times editor Bari Weiss, is not really for me, but I like to pay attention to it because I think of it as a main incubator for a still-cohering strain of political conservatism I call “Substackism.” For me, the best way to understand the Free Press is as a political project aimed at synthesizing at least some of the multiple, shifting, and often incoherent strains of “anti-woke”-ism that have emerged in the Trump era with the largely discredited Bush-era neoconservatism on behalf of which Weiss has argued for most of her career. There is some obvious existing common ground between neoconservatives and anti-wokes (an antipathy for left-wing politics and an intense anxiety about crime and urban life) and some fertile new territory to be sown (deep suspicion of trans rights, politics, and medical care). But there are subjects about which the ideological settlement has yet to be determined, the most obvious being foreign policy: Neo-conservatives are legendary militarists, while anti-wokes, to the extent there is a coherent foreign policy that can be attributed to them, tend toward isolationism, if not outright sympathy to American rivals like Russia.

I call this still-inchoate synthesis, which is the main contender for post-Trump conservatism (non-Nazi, non-Evangelical division), “Substackism,” because it seems to me that its contours are being worked out on Substack, at the Free Press and many of its ideological peers and interlocutors, like Michael Shellenberger’s tremendously insane newsletter “Public.” It’s an ambitious fusion program, one that has some precedent, and it’s interesting to watch a sharp political impresario like Weiss try to graft together a coalition out of COVID-radicalized parents, obsessive transvestigators, lead-addled Gen Xers, China hawks, tech billionaires, and war criminals, among others. But Substackism is still more of a media phenomenon than a political coalition, and the final settlement hasn’t been reached yet. If neo-conservatives get foreign-policy adventurism, what do the anti-wokes get in the negotiation?

This is the context in which I read the launch edition of Nellie Bowles’ new semi-regular feature “Free Press Health,” a health-news roundup accompanied by the tagline “A new series for people who don’t want plastic in their water or bugs on their plate.” Bowles, an excellent tech reporter and weekly Free Press columnist, writes that “the mainstream press is losing credibility when it comes to health and science news… there is a thriving, incredible world of smart new health and science writing and podcasting. But it’s hard to figure out who or what to trust when you’re beyond the gatekeepers.” (This is very classic Free Press third-way positioning--hostile to the “mainstream,” but also wary of the fringes, trying to seek out the middle ground on which it has the surest footing.)

I suspect that if you spend some time on and around Substack you can guess at the topics that make up the newsletter: microplastics, CDC errors, antidepressant prescriptions, COVID origins, meat-eating, bug-eating, autism rates, puberty blockers. I don’t want to litigate the validity of each item--all of these topics are legitimate and in some cases genuinely pressing public-health and environmental issues, and besides, part of the fusionist, respectable, Free Press flavor of the column is that Bowles is restrained and well-sourced in her write-ups. (Indeed, I had previously been informed of about half the newsletter’s items by the very mainstream press it was warning me against.) But as a constellation of subjects this is a familiar one, and if you added “testosterone/sperm count” you’d have a pretty good list of the top-of-mind concerns of anti-woke, government-skeptical health-and-wellness Substackers with whom Free Press is making common cause.

The anti-woke wellness corner of Substack is just one portion of a large and loose network of influencers, podcasters, gurus, scientists, pseudoscientists, quacks, dieticians, and scammers, consideration of which in its fullness is probably outside the scope of this short newsletter item. But what links all of these diverse content producers together is less a particular level (or absence) of scientific rigor or expertise (sometimes these guys are absolutely correct!) and more an outsider attitude--a mistrust of institutions and a sense of pervasive environmental contamination. (In the same way that what seems to animate, say, the Times’ “Well” section is also not really rigor--it often over-covers and over-extrapolates from studies as loosely and shallowly as any podcast host--but a desire for expert approval.) This anti-institutional attitude has also helped cement a particular political valence that I associate with the broad anti-woke reaction. Over the past decade or so, just like everything else in American life, outsider-driven “alternative” medical and wellness beliefs have become increasingly (as the kids say) right-coded. Either way, its popularity is undeniable. (Not to mention unsurprising--in some sense there is nothing more American than the peddling and consumption of diets, programs, protocols, and miracle cures.)

I don’t want to overstate the novelty or the extent of the realignment around welness--there has always been a political valence to attitudes about health, and the left has never had a monopoly on woo. But in general, for most of the post-war era, elite conservatives were able to quiet and marginalize the fluoride skeptics and snake-oil merchants that populated the conservative coalition. (I don’t think of William F. Buckley’s National Review, as a comparative example, as being particularly curious about “health” as a subject, though as I type that I get the feeling someone is going to email me a page from the magazine where Buckley hawks some bizarre diet plan or something.) But 2024 is (obviously) different from 1955, and a fusionism for the current historical conjuncture is going to assemble itself differently. If you want to entice some of the politically incoherent, anti-woke, I.D.W.-type voters into your coalition, you need to attend to their concerns. And what they seem to consistently prioritize as an issue--or at least, what they seem to want to read about--is “health.”

Further reading in this vein:

The genealogy of the “Apocalyptic Systems Thriller”

Longtime readers know that there is almost nothing I like more than newly invented genres, schematic cultural taxonomies, trend and fashion genealogies, and pseudo-academic classifications, and for this reason among others I enjoyed reading the novelist Hari Kunzru’s articulation of a new genre he calls the “Apocalyptic Systems Thriller”:

Multi-stranded, terse, often anchored in character just enough to drive the action forward, these books invite us to take an elevated, panoramic view of events that extend too far in space and time to be grasped by a single narrative consciousness. Conflict, climate change, pandemics and natural disasters offer ways to contemplate our interconnection and interdependence. At its best, this kind of fiction can induce a kind of sublime awe at the complexity of the global networks in which we’re enmeshed: A butterfly flaps its wings in Seoul and the Dow crashes; a hacker steals a password and war breaks out.

The currency of the A.S.T. is plausibility. It can be counterfactual, but never fantastical. It differs from other kinds of thrillers in its willingness to indulge in essayistic digressions about technology or policy. In some cases, the story may even take second place to these ideas, a mere vehicle for the delivery of an info-payload. In this, the A.S.T. is essentially a subgenre of SF, or at least the kind of science fiction that prioritizes world-building over other kinds of narrative pleasure. Indeed, many A.S.T.s, like “2034” and “2054,” are near-future tales, extrapolating from the present to a carefully imagined next five minutes, designed to elicit a little spark of recognition, the feeling of being shown a possible path from “here” to a utopian or dystopian “there.”

This sounds like, as they say, extremely my shit, and I suspect it is extremely the shit of many Read Max readers as well. But Kunzru only provides a handful of examples, and I’m not sure how many count as full-throated recommendations: The exemplar for Kunzru is 2054, a new thriller by Elliot Ackerman and Admiral James Stavridis (former Supreme Allied Commander for NATO in Europe), and its predecessor 2034, by the same authors, which was billed as “a novel of the next world war.” He also cites Kim Stanley Robinson’s Ministry of the Future, Lawrence Wright’s pre-COVID pandemic novel The End of October, and AI 2041, co-written by Chinese sci-fi writer Chen Qiufan and the former president of Google China, Kai-Fu Lee.

In a smart response at his substack Programmable Mutter, Crooked Timber’s Henry Farrell suggests the A.S.T. has nonfiction examples as well, or more specifically that the same balance of narrative propulsion, human agency, and deep systematic thinking can be found in books like Adam Tooze’s Crashed and his own Underground Empire with Abe Newman, which has been on my own personal reading list for a while now. He also cites Read Max favorite Red Plenty, an account of the Soviet planned economy told almost like a sci-fi story, which nicely straddles the divide between fiction and non-, though I don’t think it’s fair to call it apocalyptic.

I would be interested if Read Max readers have other A.S.T. suggestions, either fictional or not. Two (nonfiction) books that come to mind are Misha Glenny’s exploration of overlapping multinational crime syndicates McMafia, and the excellent and extremely thriller-ish Dead in the Water, about a murder that sheds light on the entire global shipping complex. (N.b. to free readers: if you were a paying subscriber you’d have been recommended both of these excellent books months ago in editions our subscriber-only weekly recommendations roundup. Sign up here for the bargain price of $5/month or $50/year.) But I’m not sure either of those really qualify as “apocalyptic,” even if they’re systems thrillers, since the global phenomena that illuminate the interconnectedness of the contemporary world in those books are “crime” and “shipping,” respectively.

Where does the A.S.T. come from? Kunzru cites some obvious precedents--Tom Clancy, Michael Chrichton, cyberpunk. (Interestingly he doesn’t mention “systems novels” at all, even though to me “Tom Clancy writing a Thomas Pynchon book” is not the worst gloss for defining A.S.T.) I’d add Ursula K. LeGuin to the list, especially the ambiguously utopian novel The Dispossessed, which in the depth of its political-economic world-building seems to me to be one of the biggest influences on Kim Stanley Robinson’s career. Kunzru also intriguingly suggests as a forebear corporate scenario planning, of the type that the RAND corporation specializes in:

Wack’s scenario planning was credited with helping Shell weather the oil shocks of the ’70s, and this style of “possible future” storytelling gradually spread beyond the company, finding fertile ground in the emerging Bay Area tech scene. By the 1990s, the founder of the Whole Earth Catalog, Stewart Brand, was a partner in a scenario planning consultancy. Wired magazine ran a “scenarios” issue in 1995, detailing possible futures imagined by writers of speculative fiction like Stephenson, Bruce Sterling and Douglas Coupland, completing the fusion of scenario planning with more traditional literary pursuits.

So, while the A.S.T. is a form of entertainment, it’s also meant to enlighten the planners and decision makers who might grab a hardcover off the shelf at an airport bookstore. Bill Gates and Barack Obama have recommended “The Ministry for the Future.” Robinson spoke at the 2022 World Economic Forum in Davos. Stavridis and Ackerman have spoken at think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute, the Atlantic Council and the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs. As fiction for the Davos set, the A.S.T. is a tool for both forecasting and navigating the troubles to come.

As a kind of pulpy political or policy writing, the A.S.T. reminds me of another genre of speculative fiction: “invasion literature,” which at its most narrow refers to the pre-WWI English phenomenon of novels and stories written about a hypothetical invasion of Britain, usually by Germany. Emerging at the same time as the earliest spy novels, and animated by shifting geopolitical terrain and rapid technological change (sound familiar?) invasion literature was often written by veterans or military officers and sometimes even featured specific strategic or tactical recommendations. Not much of that era’s “invasion literature” is read these days (unless you count the distinctly anti-war War of the Worlds) but the most famous and arguably the first true example is “The Battle of Dorking” by George Chesney.

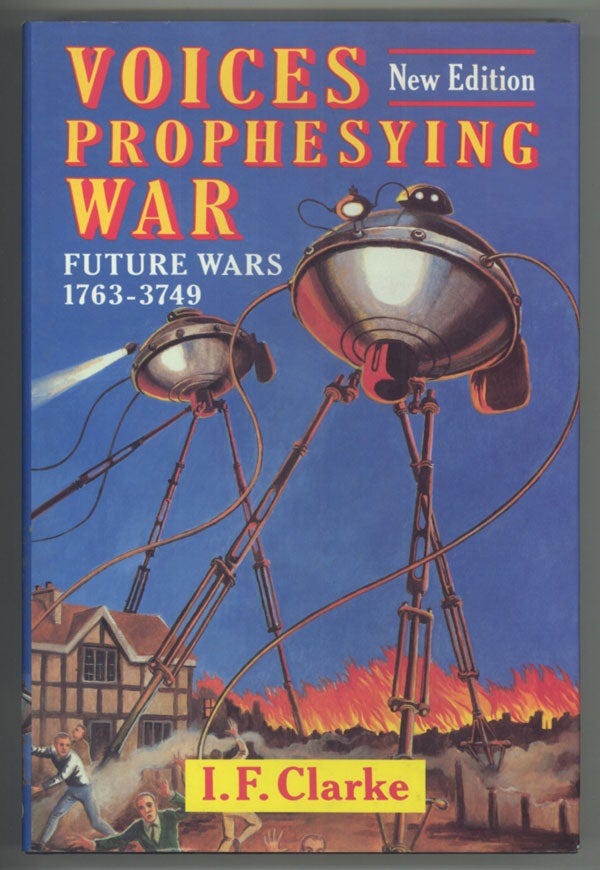

I don’t know that there’s very much good invasion literature, and I can’t say I recommend “The Battle of Dorking,” but if you’re interested in the idea there’s a cool book called Voices Prophesying War: Future Wars 1763-3749 by the late scholar I.F. Clarke that covers both the classic phase of invasion literature and also the many post-WWI examples, of which Stavridis and Ackerman’s book is an obvious example. (I recommend getting the updated 1992 edition even though the 1970 one has the sickest cover, as seen here.)

I find new “wellness community” very interesting because they look at corruption in the medical industry and instead of drawing the conclusion of “a for profit healthcare system can incentivize unethical behaviour in the pursuit of profit” (a good example of this is Purdue Pharma’s role in the opioid crisis) they completely go off the deep end and start yelling about how how woke vaccines will make your children gay.

they are rightfully suspicious of the healthcare system, but instead of arguing for reform and medicare for all, the seem to draw the worst conclusions possible.

you’ve probably read, but Naomi Klein’s Doppelgänger is very good on the “alt wellness” post-covid political shift!