True Life: For reasons I don't fully understand I bought hundreds of Cold War-era military slides on eBay

A guest post from Sam Biddle

Greetings from the new Read Max HQ, located ten minutes’ walk east of the old Read Max HQ, in world-famous Brooklyn, N.Y.! The move has been completed, sort of, and starting next week Read Max will return to its regular twice-weekly schedule.

Today’s edition is a guest post from Sam Biddle, a writer for the Intercept and Read Max’s Chief Roving Cold War Paranoia Correspondent, regarding some old slides he bought on eBay. (Longtime Read Max readers will recognize Sam as the instigator for the classic demonic-artifact eBay seller post.)

Before the main event, a note: My friends at the cooperatively owned sports site Defector are running a reader survey, located at this link. If you don’t know Defector, you should check it out; if you like this newsletter there is a high probability you will like Defector as well. Anyway, they asked me to link to it here because they believe that the Read Max audience is “Defector-adjacent,” which sounds right. (My audience is bored programmers with disposable income and theirs is bored lawyers with disposable income.)

The Slides

by Sam Biddle

I lobbied my very patient girlfriend for months before she agreed to let us get a file cabinet for our tiny house. Her argument was that the cabinet would quickly fill up not with “important documents” or “work papers” (as I claimed), but with “dumb bullshit we don’t need.” For evidence she pointed to our kitchen drawers, which are crowded with abandoned USB cables, forgotten hard drives, and warranties for purchases long since lost or ruined. My argument is that this is not “dumb bullshit.” Do I sometimes lay on the couch for long stretches, contemplating the Minidisc, browsing old compact Sony electronics on eBay? Yes. Do objects essentially teleport from a stranger’s household junk zone to my own? Yes. Is there an inexplicable and lonely Dreamcast on the top shelf of one of my two closets? Well, yes.

But I promised my girlfriend that I wouldn’t let these cabinets become a home to a disquieting tangle of electronics miscellany. Instead they would be reserved for important adult things: Bills, proof of identity, paper records of complex international financial transactions. I imagined getting a letter informing me I was about to die and carefully, silently filing it away in the cabinet.

Who won this argument? Well, today, the bottom and largest drawer of the filing cabinet is filled nearly to the brim with small red and yellow boxes containing hundreds of 35mm mounted film slides used for presentations on Cold War military capabilities and readiness. It’s a mass of plastic and celluloid that’s become known in our home simply as The Slides.

I used to think I had hobbies—reading and writing on the internet—before my work, which consists exclusively of these two acts, thoroughly ruined both. Though the internet ceased being a thrilling playground of creativity, information, and interesting strangers sometime around 2010, where else am I going to go? Like so many late-night searches for an old Walkman, my relationship with The Slides began on eBay, where, out of boredom and the ever-nagging belief I might be able to fill the psychic void with what people refer to as “a hobby,” I sometimes search for odd and interesting artifacts. I forget the exact query terms—maybe “military slides” or “cold war photos” or something else that piqued my personal and professional interests in techno-paranoia and history.

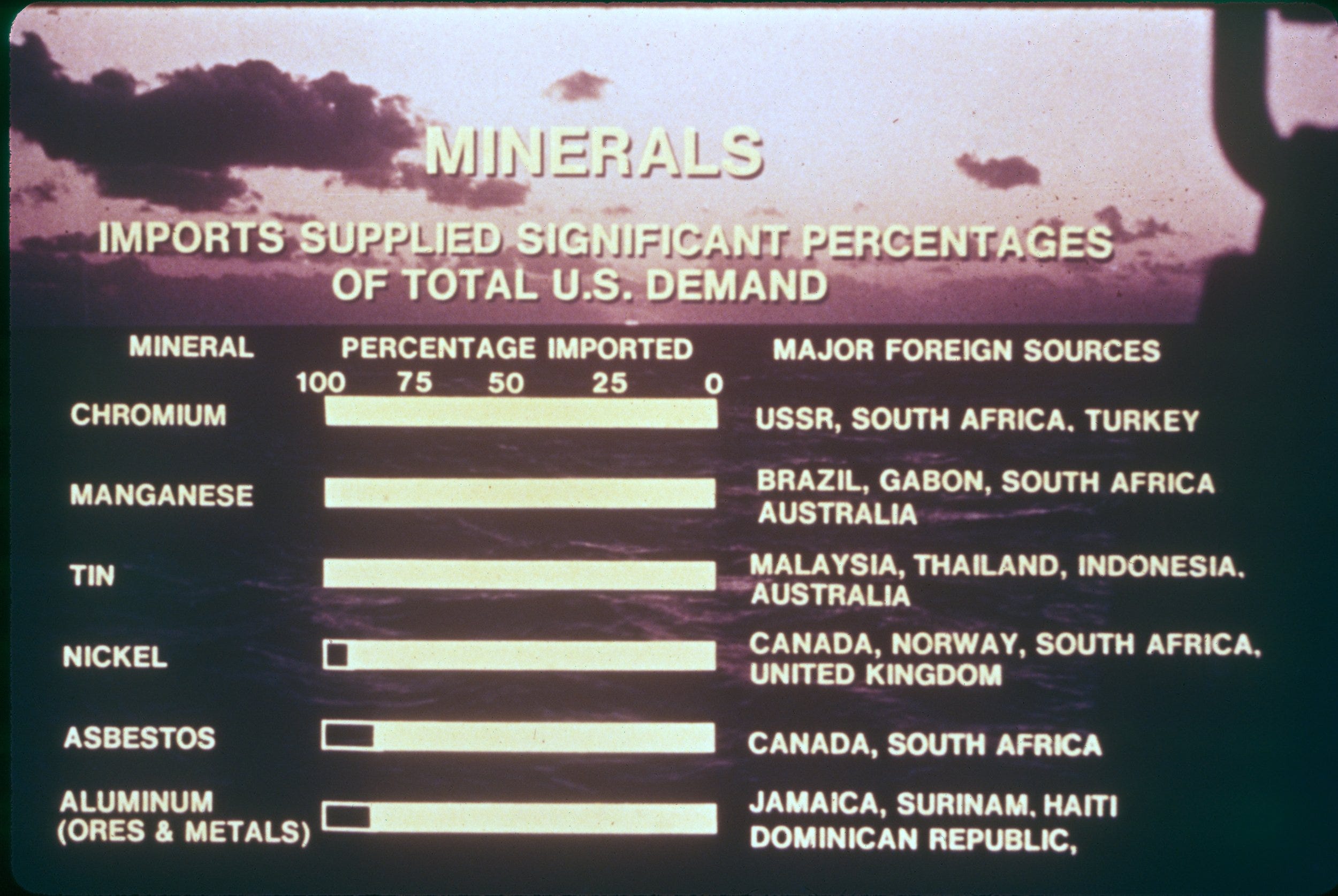

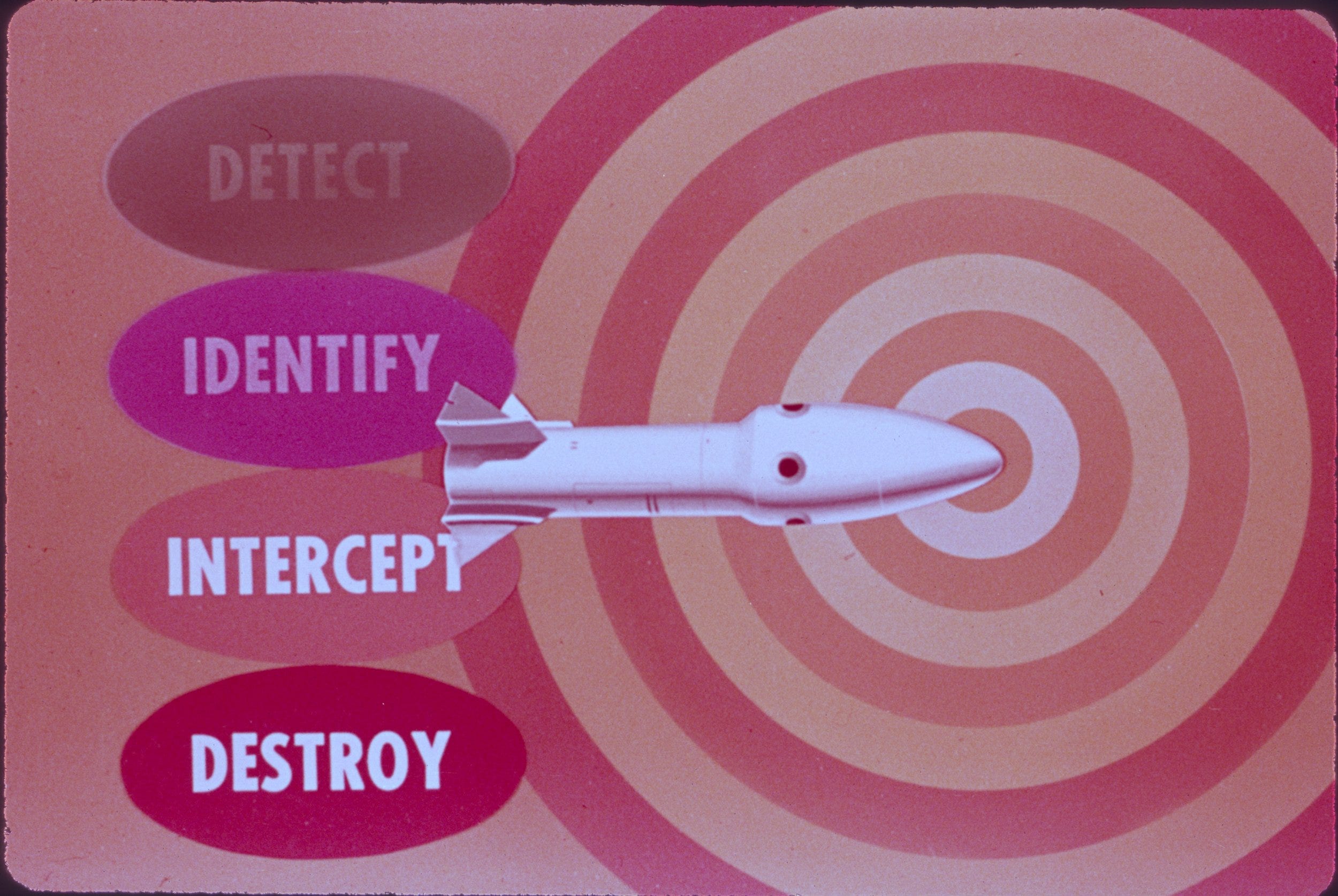

Even before their obsolesce, it’s hard to think up a noun more directly associated with deep tedium than “slides.” But the eBay listing for several boxes of 35mm slides from various military offices appealed to me deeply. As visual objects they were almost beautiful, if one put out of mind the context that they were created by a national military apparatus that threatened to literally destroy the world with nuclear hellfire if that’s what it meant to protect it from Communism. It was a treasury of lost graphic design: Hokey vintage hand-drawn illustrations, striking bold-faced typography, highly stylized maps, charts, and diagrams.

The Slides arrived quickly, discreetly packaged in enough tape and cardboard to mask my new sicko interest from my neighbors. It was an immediately pleasurable experience: Inside were five fire truck red plastic boxes, each the size of a deck of cards, and each containing a few dozen slides, essentially tiny photographs neatly sandwiched between cardboard. I wondered how long it had been since anyone even remembered these things existed. If you’re wondering whether I smelled the contents of the box, that’s frankly none of your business.

The eBay seller told me they had purchased these at estate sale in Albuquerque and believed the original owner had been an officer at Kirtland Air Force Base, a sprawling complex on the city’s southern edge. Kirtland has been integral to the American nuclear program dating since the Manhattan Project and is today part of the Air Force Global Strike Command, vital to maintaining every president’s ability to unilaterally end human life on earth if desired. While the Soviet Union is long gone, the ability to turn Russia into a pile of glowing rocks, of course, remains. As do The Slides, now caked in dust, the fingerprints of long-dead colonels, the skin flakes of nervous ROTC members squirming in their chairs as they zoned out during another presentation on the Survivability of Command and Control. I wonder how many of these now-elderly Cold Warriors, previously the tip of the nuclear spear, remain. My grandfather spent nearly his entire working life at a defense contractor, and I kept half expecting to see him next to a glowering general inspecting a warhead or bundle of cables.

Shortly after the slides arrived, I tweeted a few crude close-up slide shots illuminated by my desk lamp, and was thrilled to find hundreds of strangers replying enthusiastically. Would I scan them? Could they use them? Were there more? Could they have them? Post-Musk ownership it’s safe to imagine the exciting engagement metrics were largely false or the result of one of the remaining engineers falling asleep on a keyboard, but I was hooked. When William Gibson retweeted the thread, I knew what I had to do: Like a character from one of his novels, I would dive headfirst into an nightmare thrill ride of military hardware and computer neurosis.

It satisfied nearly every intellectual criterion. A chance to think about old missiles? Wow. An excuse to spend endless hours thinking about scanners? Heaven. An opportunity to buy a specialized 35mm slide scanner that will make my desk look even more like the domain of a mentally ill person?1 Excellent. An excuse to use the word “digitize” a lot? My God.

The eBay seller soon followed up with a message saying they had found nearly 60 more boxes of these slides from the same lot. Would I like them at a dollar a box? I can’t think of a reply I’ve ever sent faster. Now I have The Slides.

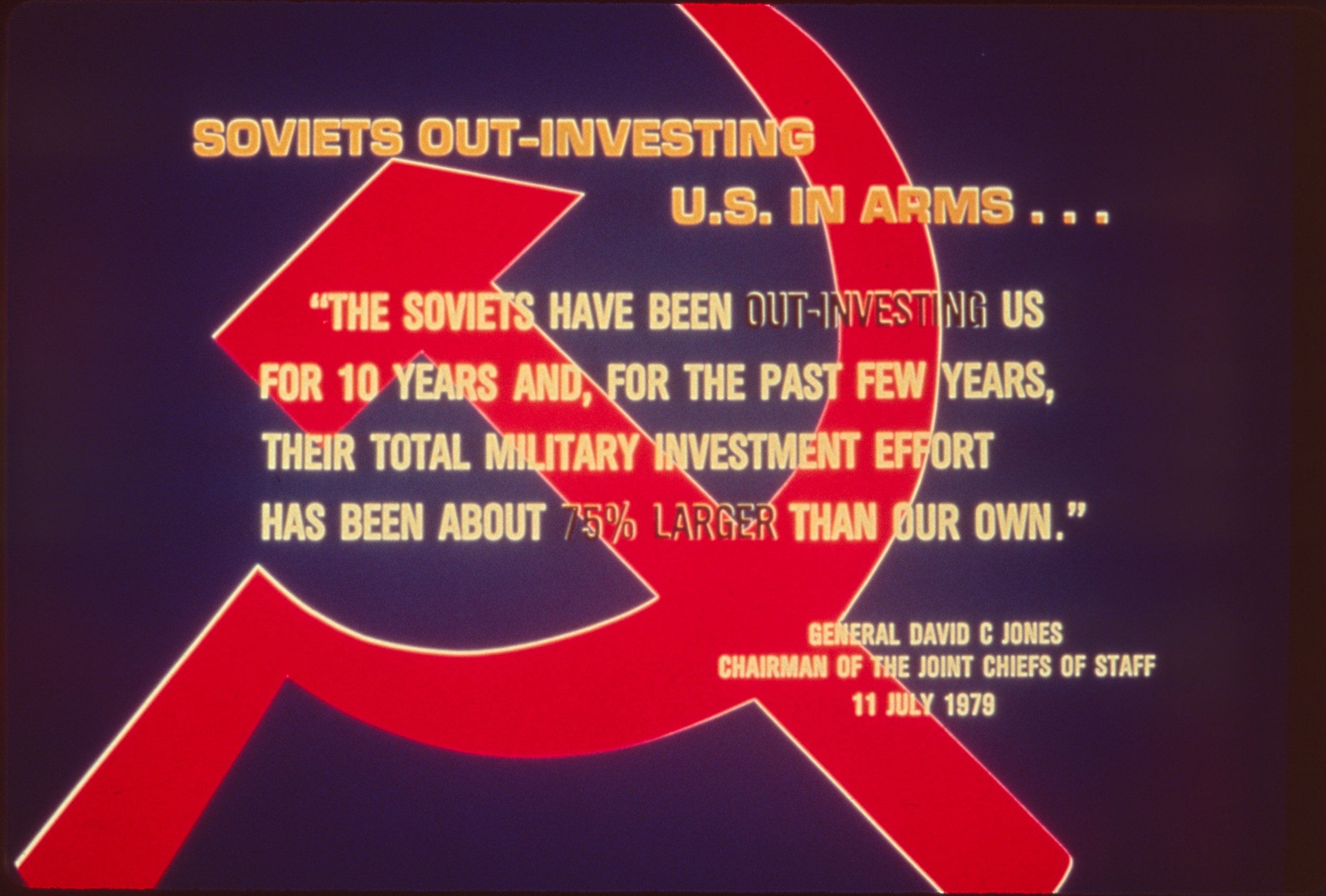

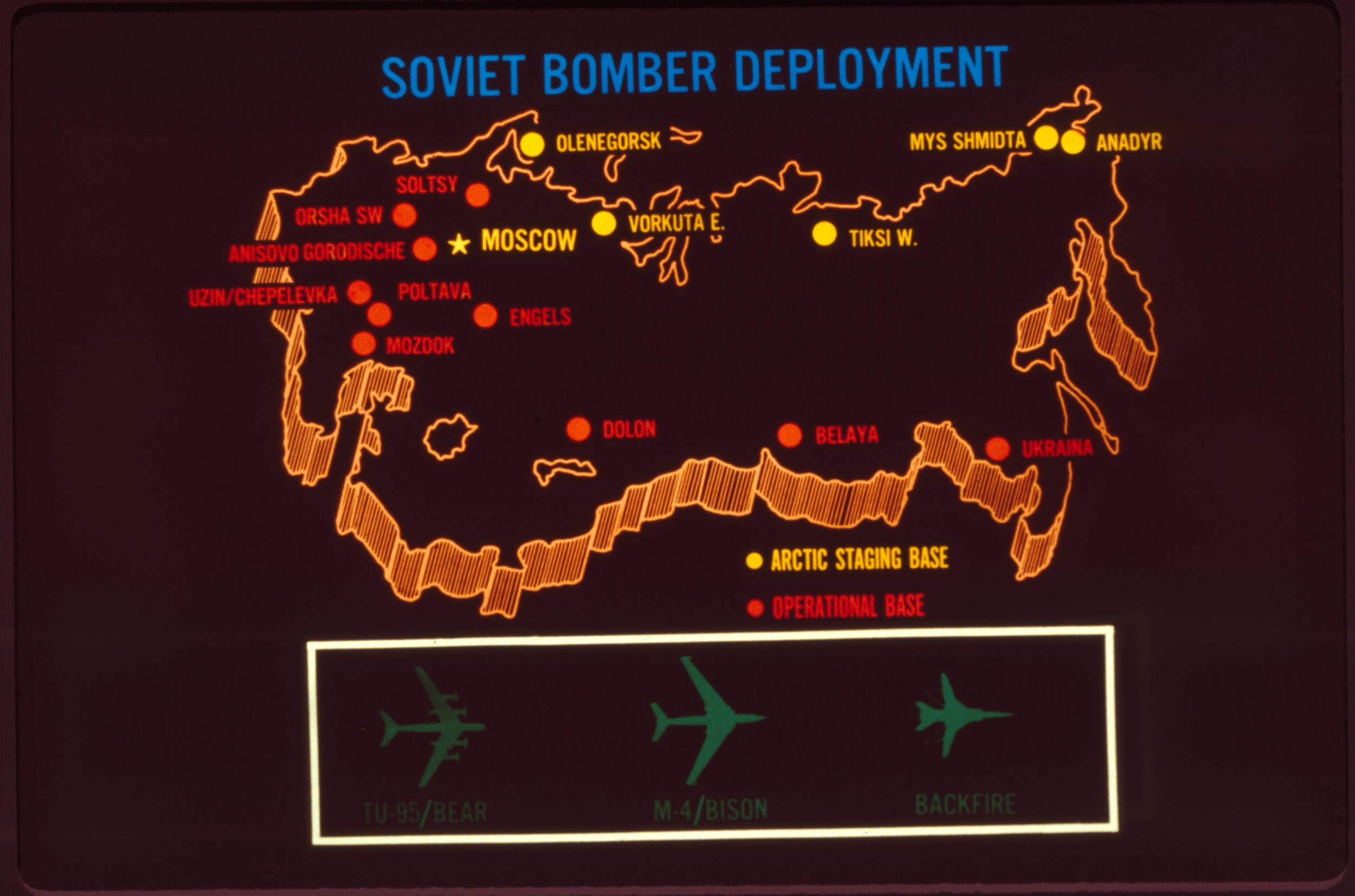

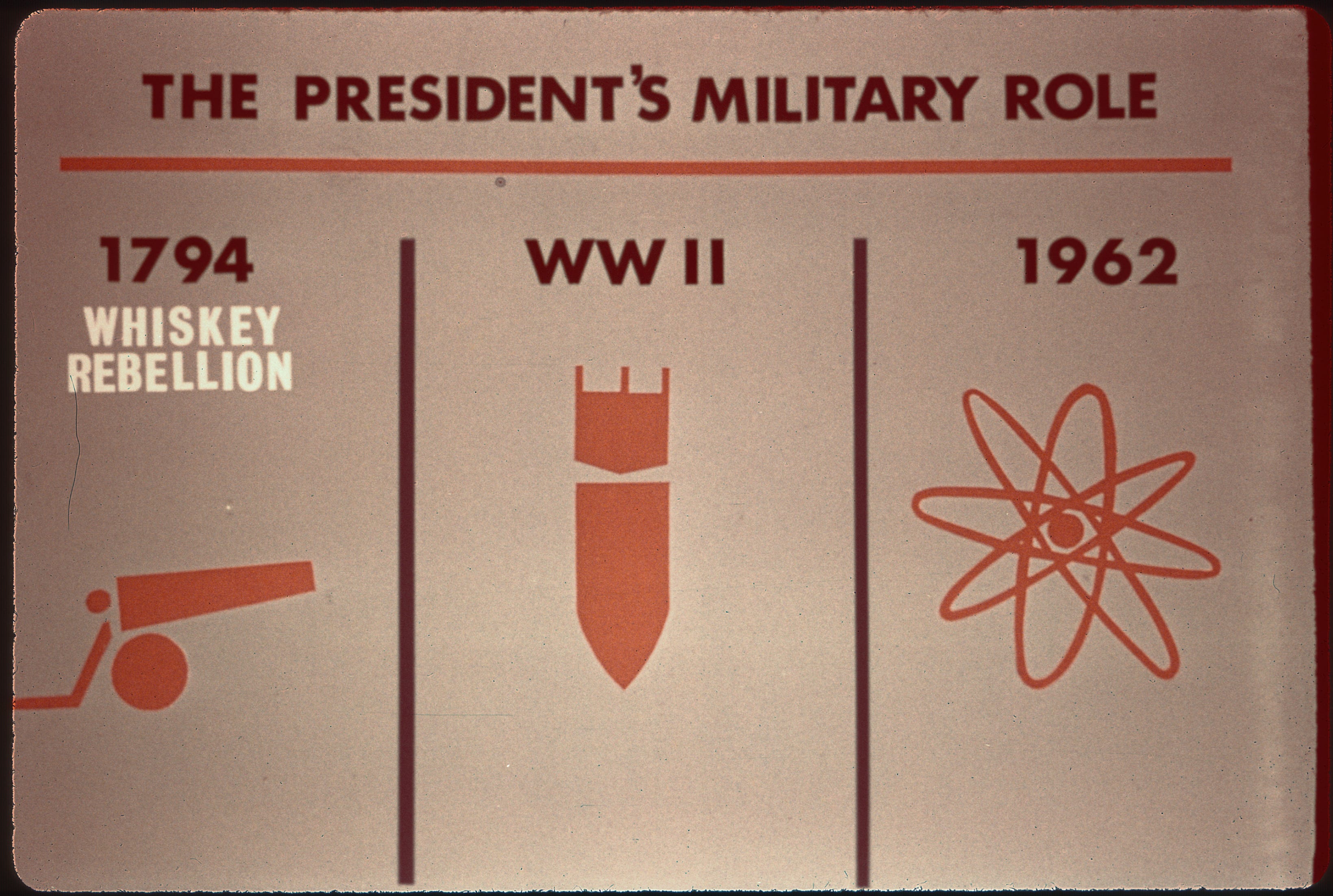

The Slides are incredible as well for their visual thoughtfulness, no matter the craziness or foolishness of the underlying idea. They are the perfect inverse of contemporary Pentagon graphic design in all its sprawling insanity, permanently poisoned by the vernacular of PowerPoint and clip art. The pre-computer Slides look as if a human with a soul put thought into how they would communicate information—words like “fonts” and “kerning” and “clarity” come to mind. Unlike a military presentation of the 21st century, which generally appear as if they were created by a man who’d gone insane after gazing directly at the face of an Elder Demon, The Slides are sober, minimal, even stylish. An overview of Soviet ICBM placements, with elegant glowing orange text on a solid black mass of Russia, reminds me of the Vignelli subway map. Then you remember these were basically the onboarding materials for a violent imperial hegemon at the height of its 20th century superpower, and you start feeling weird looking at the slides so much and put them away for a little.

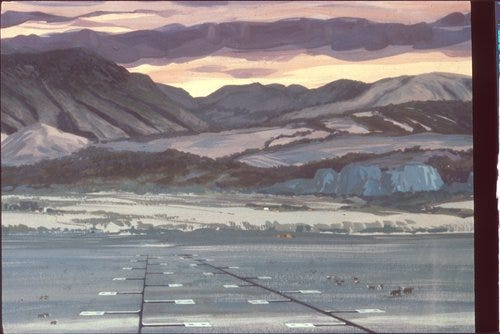

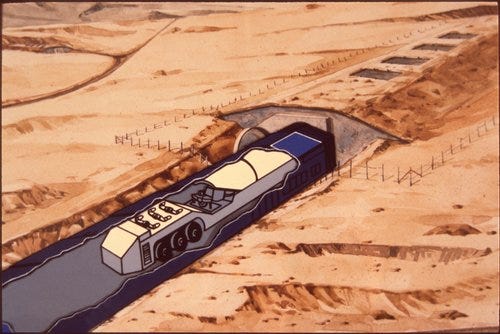

A box labeled “MX MISSILE” holds numerous watercolor illustrations of a southwestern desert landscape beneath smoldering purple sky, the terrain punctuated by ICBM storage bunkers. If you can ignore the fact that each of these bumps contains radioactive death, they look like paintings from a doctor’s waiting room or a beach rental. The MX, later known as the Peacekeeper, was an ICBM designed to simultaneously rain down on its target—Russia—ten separate nuclear warheads over ten times as powerful as the one that destroyed Nagasaki.

The original plan, as depicted in these slides, was to store the missiles on tracks so they could rapidly be moved by rail in case of nuclear war, a plan so stupid it’s a little bit cute. Even Reagan thought this was moronic, and his administration later proposed, not to be outdone in terms of sheer insanity, “burying 100 MX missiles so closely together on the Wyoming prairie that incoming Soviet warheads theoretically would destroy each other as they detonated overhead,” according to a 1982 Washington Post report. The Slides capture a bygone era of great ideas.

Many of the slides are nearly impossible for me to place in any context at all other than the general fear of being evaporated by fire at any given moment. A box labeled “SOVIET MILITARY CAPABILITIES S-100-18-85 BOX 1 OF 2" contains some of my favorites so far, a slideshow of pure dread: One graphic shows a map of the United States surrounded by submarines, another slide presents the glaring portraits of Soviet High Command. A slide titled “SOVIET GLOBAL POWER PROJECTION” is an exercise in psychological projection, warning the audience that the Russkies are increasingly selling arms to and building bases in countries around the world.

Some of my favorites are just fragments: The words “ATTACK WARNING” on a blue background:

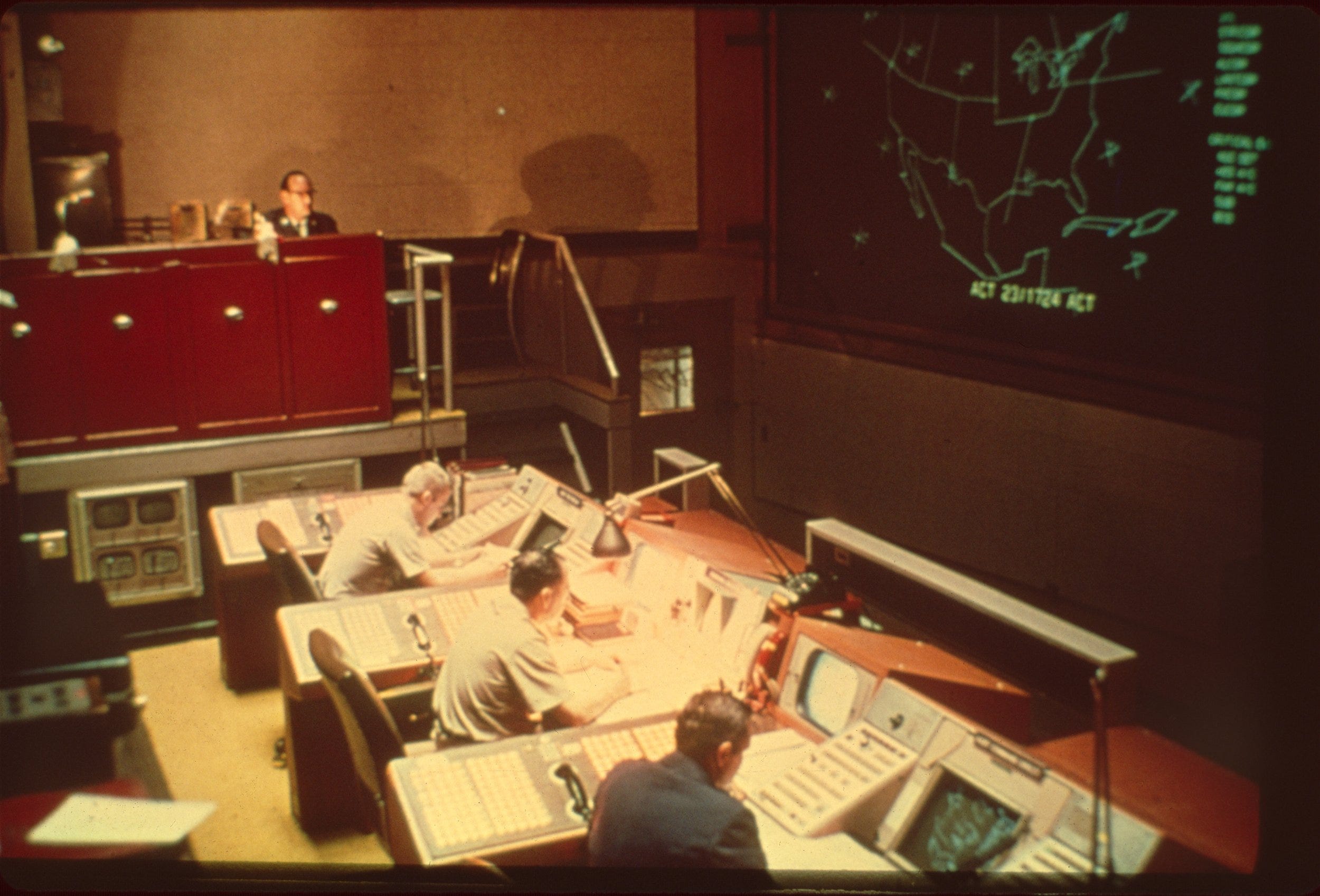

Three men from NORAD sitting in short sleeves, staring at blinding-green computer monitors, perhaps awaiting annihilation, while a fourth watches them:

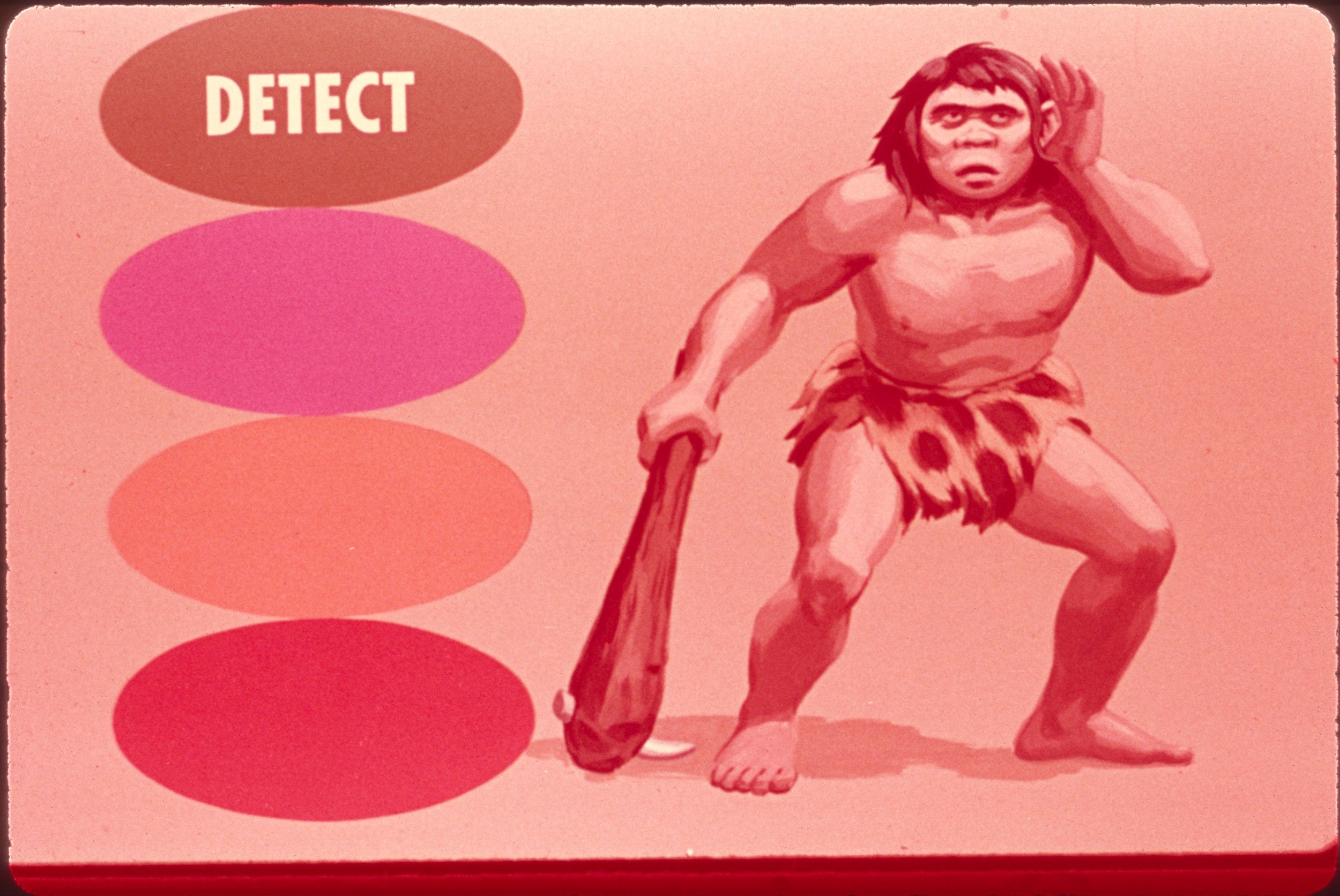

A drawing of a caveman, hand cupped to ear, labeled only with the word “DETECT.”

Like many of the slides, the film substrate containing the image of last one has faded greatly, taking on a pinkish-orange hue. I’ve spent countless hours agonizing over this color fading, as I’ve come to agonize over every aspect of The Slides. (It took maybe three or four days for my fun nerdy meaningless little project to become a pressure cooker of anxieties and imagined doom.) Many of the images are pink, or orange, or blurry, or dirty, or perhaps they looked like shit decades ago when they were slotted into a projector. There’s no way to know. So do you fix them? My hobby quickly, inevitably, took a deeply obsessive turn. What should have been one of the lowest-stakes undertakings of my adult life became something keeping me up at night. Was I using the right settings? Were uncompressed TIFFs really worth the space? At what point does resolution deliver diminishing returns? Have I been scanning these fucking things backwards the whole time? Do I have to start over again? When was the last time I had a conversation with my girlfriend that wasn’t about The Slides?

I began consulting experts, who naturally largely contradicted each other because there is no right answer. The National Archives suggest applying a light, tasteful sharpening filter as a matter of course, while some photographers and archivists who were generous enough to let me waste their time said this was unthinkable. I should preserve what’s left on the material plane, they said, scan what’s really there, upload the tinted, blurry truth, for posterity, and let future generations adjust the colors if they want.

Future generations? I have at times, my desk covered with Slides, wondered “what the fuck am I doing exactly,” for which there is also no good answer. As I write this, I’ve digitized seven out of about 60 total boxes, meaning I have hundreds of slides left to go, and Christ only knows how many hours for each. After I’ve finished The Slides, I have Even More Slides, a whole other batch from a different seller. Unlike the others, these were taken from the archives of Litton Industries, a defunct defense conglomerate that at one point in its history, like a Simpson’s joke come to life, owned divisions manufacturing both military hardware and Stouffer’s frozen foods, of French bread pizza infamy.

Am I enjoying this anymore? Was I ever? Was I only in this for the weird single-use scanner? Is anyone even looking at these? Does it matter? I have an activity, and I’ve learned, and I’ve preserved information that maybe a handful of weirdos like myself will enjoy. Like any good hobby, this definitely isn’t “fun,” but it is vaguely gratifying and “something to do that has no economic purpose whatsoever.” I guess I could be making neat piles of rocks outside or birdwatching and achieving more or less the same, but then I couldn’t have bought a niche scanner.

Sam Biddle is a writer and technology reporter for The Intercept. His scans of The Slides can be found here.

If you enjoyed this post, you might also like these tales of nuclear paranoia, eBay freaks, and gadget neurosis:

The actual scanning process is elaborate and time-consuming as an occult rite. At first I had hoped the (very expensive) flatbed photo scanner at the local library, which could process 15 slides at a time and would cost me zero dollars to use, would be more than sufficient. This was foolish: I convinced myself the results were slightly blurry and unsuitable for my audience of completely imaginary people who cared about what I was up to. Instead, I opted to buy a used Plustek OpticFilm 7600i SE, a bread loaf-sized device made specifically for scanning mounted slides—one at a time. Before you even press a button, each requires a careful dusting with a brush, perhaps a puff of compressed air, and even a ginger microfiber rub-down. Although one archivist reassured me that I “won’t hurt the film physically unless you pour acid on it or light it on fire,” I handle each like a treasure. Once cleaned, the scanning software will, very, very slowly, turn the tiny photograph inside into a TIFF image file, a digital image format created back when some of these slides were. This required hours of carefully calibrating the scanning app’s settings, a process akin to communing with an angry spirit, sinking me into delirium as I tried to figure out whether I’m the first human in the history of the species to be able to tell the difference between a photo scanned at 3600 versus 4000 DPI. In search of answers, if not peace, I’ve scoured endless Reddit threads, long-forgotten early aughts message boards filled with Germans arguing about image sensors, memorized university library resources, and sat patiently through YouTube tutorials. But as tedious as this sounds, the tedium has only begun when you hit "scan."

Hi everyone, thanks for reading. I forgot to mention in my post for our friend Max, if you want to check out the uncompressed high resolution copies of the slides as I digitize them, I'm (gradually) putting them all up on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/@sambiddle

I'm also putting them on my site if you don't need giant TIFF files: https://sambiddle.com/35mm-scans

Thanks very much for your interest, your comments make it worthwhile to me

this rules so fuckin hard i can hardly believe it. preserving rare and historically significant human knowledge is basically a holy mission and as much as you downplay it as an insane obsession (an assertion which entire academic fields would find insulting), i think you must know you're doing something genuinely cool and good.