The bombsight eye

Envisioning nuclear war

You’re reading Read Max, a newsletter about the future. This is a Wednesday column and is free for all readers. If you find it interesting, please share it with others.

If you like Read Max, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscribers get access to all Read Max content and a sense of satisfaction and peace from supporting independent journalism.

I’ve been thinking this week, for no particular reason, about nuclear war. On Sunday, I visited one of my internet safe spaces: Alex Wasserstein's NUKEMAP. NUKEMAP allows you to model the effects of a nuclear warhead detonation at the location of your choosing, e.g., a 800-kiloton Russian Topol SS-25 ICBM detonated a couple kilometers in the air (so as to maximize damage) above downtown Manhattan:

I was not the only person to visit NUKEMAP this weekend, apparently: The site has been receiving so much traffic that Wellerstein put up a mirror. This is probably not surprising. Americans (about a third of Wellerstein’s traffic comes from the U.S.) have loved to imagine themselves getting nuked since Americans first nuked someone else, as geographer Derek Gregory writes in his essay "Nuclear Narcissism."

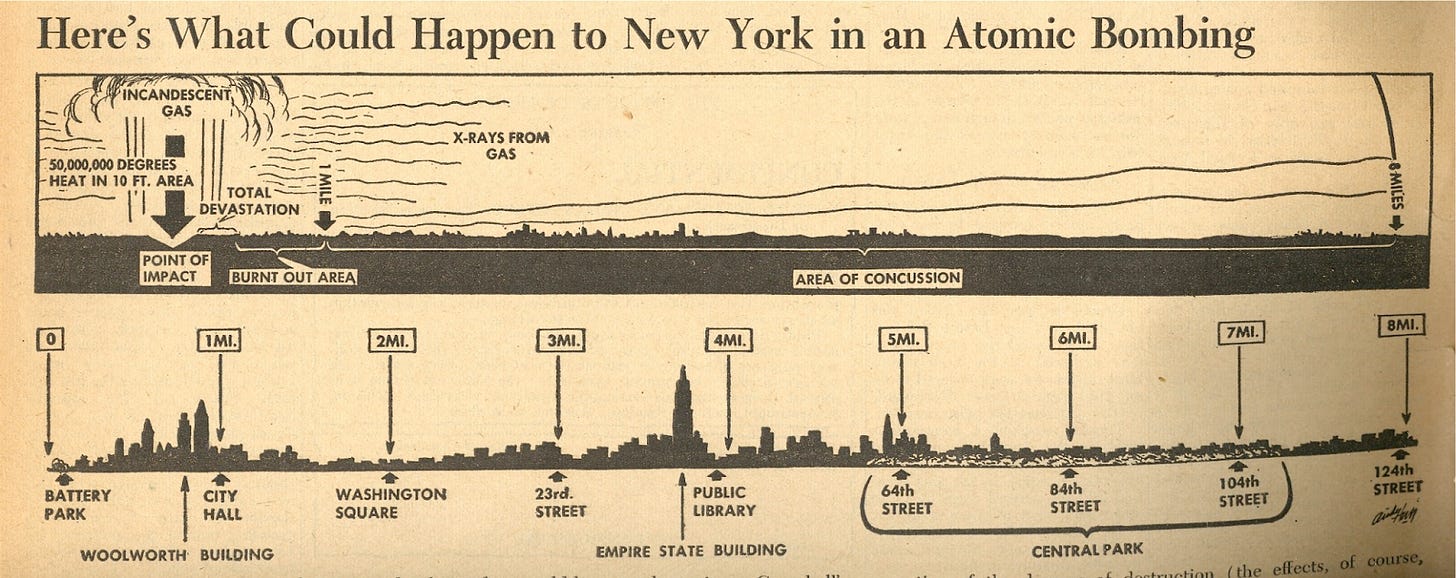

A few years ago John Ptak of JF Ptak Science Books1 posted this remarkable illustration of the range and effects a blast centered in downtown Manhattan (at about the same spot I simulated on the Nuke Map above) in the August 7, 1945 issue of the left-wing daily PM. (August 7, 1945 is, of course, the day after the U.S. dropped the “Little Boy” atomic bomb on Hiroshima.)

PM’s horizontal view, which assumes the perspective of a civilian on the ground, is striking compared to the images that would be produced over the next half century, the vast majority of which would assume the perspective of the bomber. In his post about American visions of nuclear attack, Gregory quotes a great essay by the historian of science Peter Galison, "War against the Center":

Perhaps before Hiroshima the bombsight eye had already begun to reflect back. I don't know. But in the atomic rubble, as the analysts interviewed hundreds of blast survivors and canvassed the broken structures, as they methodically noted which kinds of concrete walls still stood at various radii of destruction, they began, quite explicitly, to see themselves, to see America, through the bombardier's eye. They began to wonder what an American city would look like after the bomb had fallen. Returning to the United States and publishing their Strategic Bombing Survey, things began to look different. They began to see themselves, their towns and factories, on the crosshairs of radial targeting maps. Far from a technological determinism, the all-too material technologies and concepts of self were fully imbricated.

This graphic, for example, published nine years later in the New York Times, looks more familiar:

Or, for Angelenos, this illustration from a 1961 issue of the Los Angeles Times, also from Ptak's blog:

If you want to see damage radii for Chicago or San Francisco, you can watch the short film One World or None, produced by the Federation of Atomic Scientists in 1946:

The cinematic tradition of nuclear-terror short-film continues these days on YouTube. A couple years ago Princeton University’s Program on Science and Global Security put together "a new simulation for a plausible escalating war between the United States and Russia," one starting, not reassuringly, "in the context of a conventional conflict" between NATO and Russia. In this scenario, an all-out nuclear war between the world's two biggest nuclear powers, 91 million people die in a matter of hours:

The big-NORAD-screen aesthetic of Plan A — talk about “the bombardier’s eye”! — isn’t quite as striking as the skull-and-crosses used to trace the outer limit of the blast in One World or None. But it’s better than a lot of the other YouTube stuff.

Of course, for the last 80 years no one has been imagining thermonuclear war harder, and in more detail, than the U.S. government. Here, e.g., is an early map produced by the AEC to show the range of fallout from a thermonuclear blast by taking the actual fallout from the Castle Bravo test and laying it over the the Acela corridor.2 As Wellerstein puts it, "Superimposed on an unfamiliar atoll, it’s hard to get a sense of how long that plume is. Put it on the American Northeast, though, and it’s pretty, well, awesome, in the original sense of the word." One reason to imagine nuclear detonation in the U.S. is to contextualize it for the most parochial of nations:

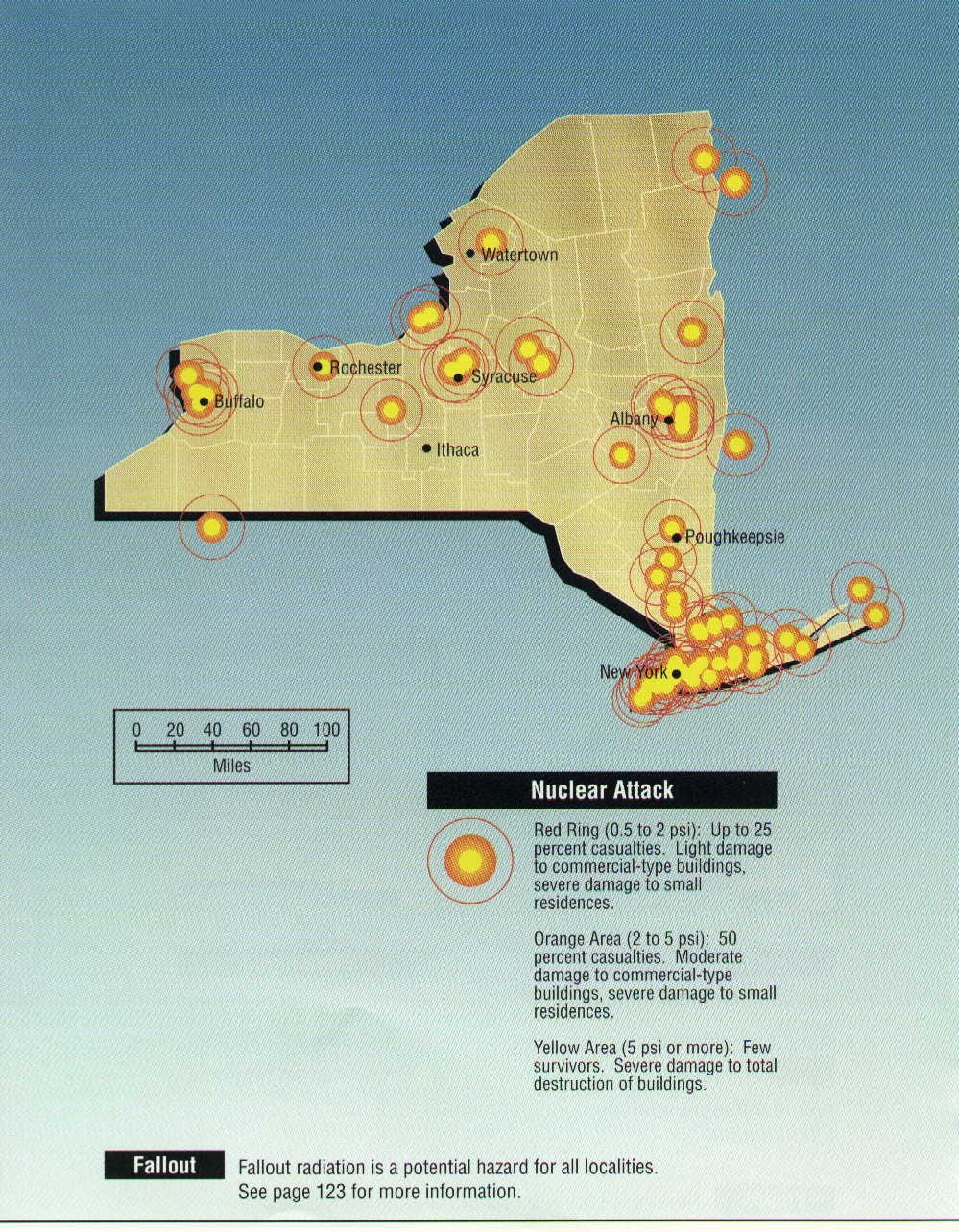

Another reason to imagine nuclear war is to prepare for it. This 1990 FEMA booklet3 outlining potential or expected nuclear targets state by state has been circulating on the internet for a while. (It's available here, with some other maps, as an Imgur gallery.) Here's New York:

Hmm. Not looking good for me, frankly.

The U.S. was of course not the only government to put together lists of possible targets of nuclear strikes. The U.K.'s 70s-era "hit list" was reported in 2014 by Rob Morrow in The Guardian, which put together this slick little map:

But the Ministry of Defence, as far as I know, didn't produce a map themselves, at least not one for wide consumption. The hit list was just that — a typed list, photos of which you can see here.

This map of supposed targets in the Netherlands in 1969 pops up on Reddit every couple years; my Dutch is not good enough to find a source, but it looks like a modern rendition:

The countries of the Warsaw Pact obviously must have had their own lists of likely targets, but it's harder to find maps of those. The below image, purportedly showing a wargame simulation produced by the Polish military in the 1970s (and smuggled out to the west via the CIA asset Ryszard Jerzy Kulinski), has been circulating around the internet for years. (I can't really find a solid source on it, but it'd be a very elaborate fake.) Here you can see what Polish intelligence thought targets would be, at least in the context of the simulation, in which NATO "launch a nuclear attack on the Vistula river valley in a first-strike scenario, which would prevent Soviet bloc commanders from sending reinforcements to East Germany to prevent a NATO invasion of that country." (You can also compare the Polish wargame targets in the Netherlands to the targets the Dutch imagined would be hit, on the map above.)

I haven't seen anything like this from Russia. The Pentagon's own list of Soviet Bloc targets was declassified in 2015, but in general I'm less interested in tactical plans from rivals and enemies than I am in how countries imagine their own destruction: What are the targets of strategic importance? My friend Jeb posted a great question on Ask Metafilter a decade ago called "Americans: Was your town a [rumored] Cold War missile target?":

I grew up in New Jersey. When I lived there, people would sometimes say, "You know, after [DC|New York], our area is the number-two target on the Soviet nuclear ICBM list, because of Bell Labs." I didn't really think about this too much at the time, and it seemed at least somewhat plausible. But as I've gotten older, I've heard people from all over the country say, "You know, [my town] is #2 on the Soviet missile target list because of [$feature]." [...]

Mostly, though, I'm interested in these rumors. The commonalities are:

1) #2 target. There's always a credibility-adding reference to a clearly more-valuable target. In the Northeast, this is generally DC, the Pentagon, or New York.

2) A specific reason that points to some local feature as being of strategic import, and often one that you wouldn't immediately think of, like Bell Labs (really? A lab? that's going to be ahead of a SAC HQ?)

It’s fascinating to think about the ways in which the relatively abstract geopolitical circumstances of the Cold War (and, later, the War on Terror) could affect your understanding of your own immediate environment: As Galison suggests, you might begin to imagine your town or city in terms of economic resources and military strategies. I grew up in Princeton, N.J., and it was widely understood by seventh-grade boys that Princeton was a number-two (or three, or whatever) target because of the Institute for Advanced Study, where (probably? We assumed?) nuclear scientists worked.

But as the thread reveals, everyone "knew" their town was a key strategic lynchpin that elevated it to the number-two target. Indeed, some people in the thread still insist that their town actually was (or, gulp, is) the number-two target, even though most of what we can see from simulations or from, say, the FEMA document reproduced above, suggests otherwise.

This is narcissistic, I suppose, in the same manner as using NUKEMAP to see the blast radius of a nuclear detonation over your city — to insist that you, or the place where you live, is “important” enough to nuke. It probably isn’t, but in some respects “narcissism” is the correct response, at least insofar as we’re all implicated in nuclear war: you don’t get to escape or avoid the consequences, wherever you are. Even a “small” nuclear war — one in which downtown Manhattan and Brooklyn are left untouched — is likely to plunge the entire planet into nuclear winter and terrifying famine.

If “the bombsight eye” can help us understand the scale of suffering we risk, it seems like an unambiguously good thing. But it might be good to sometimes take the perspective of the PM graphic, and to see nuclear destruction from the point of view of an onlooking civilian, as a great cloud of fire, detonated in the distance, rolling toward and threatening to engulf us, rather than from the point of view of the strategist, as a series of concentric circles, our homes in the center, over which we peacefully fly.

Ptak has a wealth of amazing scans from Atomic-age nuclear publications on his blog. My favorite might be these images from the Stanford Institute's 1960 LIVE, Three Plans for Survival in a Nuclear Attack. A good tweet would be this image and you write, like, "me after I accidentally call my boss 'mom'":

On an aesthetic level, fallout maps are among the most striking in the whole genre of nuclear-projection visualization. Look at this Saturday Evening Post map, done in watercolor:

Or this stark black-and-white map produced by the Net Evaluation Subcommittee in the late 1950s:

Or this funky fallout exposure guy from the Proceedings of the Environmental Plutonium Symposium 1971, who looks like he's just waiting for some art-hypebeast designer to screenprint him on a limited-edition heavyweight hoodie:

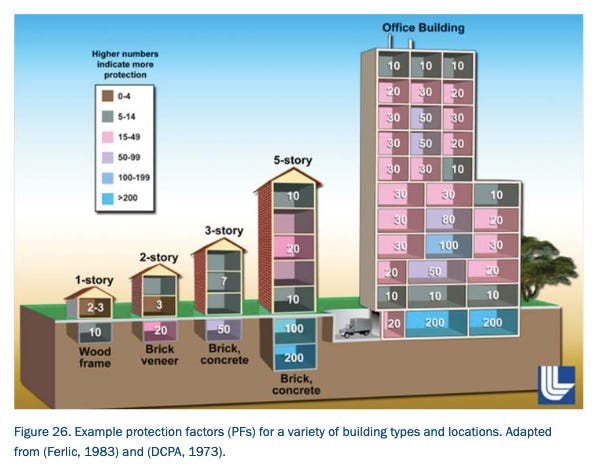

For a more up-to-date FEMA document, here's a 2011 planning document outlining effects of and potential emergency responses to a nuclear strike in or near Washington, D.C. Perhaps you'll find its visual of the locations you can be where you'll be safest from fallout useful — though I hope you won't:

FEMA also has a "BE PREPARED FOR A NUCLEAR EXPLOSION" fact sheet.

Man, I'm so glad you cited that Key Response Planning Factors document - it's been a favorite since it was published because I was living in a rowhouse then right around 11th and Clifton. I honestly think about its lessons no matter where I live now, even beyond DC.

this FEMA doc from December 2021 just went up -- Planning Guidance for Response to a Nuclear Detonation Third Edition (Draft) https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_planning-guidance-response-nuclear-detonation.pdf