Share a Coke with Hitler

A memory of Gawker

Greetings from Read Max HQ! Some housekeeping notes before this week’s column:

(1) I’m still collecting stories about awful A.I.-related meetings and other horrific A.I.-related work interactions for judicious use in a future newsletter. I’ve already got some good (terrible) stories about strange meetings and conversations in tech and media companies, on the vague topic of A.I., held by babbling managers and administrators with no clear sense of what they’re doing or why. Does that sound familiar?1 Please email me (or comment below). Anonymity guaranteed.

(2) We have a handful of Read Max caps still available for sale at the official Read Max e-commerce portal! Many people received their hats last week to rapturous reviews2; if you ordered yours but haven’t received it yet, the next shipment will go out Saturday. Order today to be a part of it!

Please note that the first run of hats feature a misprint--the correct phone number for the Read Max office is (843) 732-3629, not (847) 732-3629. This mistake has been corrected for current and future runs.

In July we move out of our apartment, which means it’s time for a purge. We’ve lived in this place for more than a decade, and accumulated many things, among them a two-and-a-half-year-old, who has himself accumulated a number of things to which he has his own strong attachment, like the small pile of rocks that has been sitting on the cabinet in our living room for more than a month now and which we are forbidden to disturb. Some things, like the two-and-a-half-year-old, we need to bring with us to the new place; other things, like (please don’t tell him) the pile of rocks, will need to be sold, donated, or discarded.

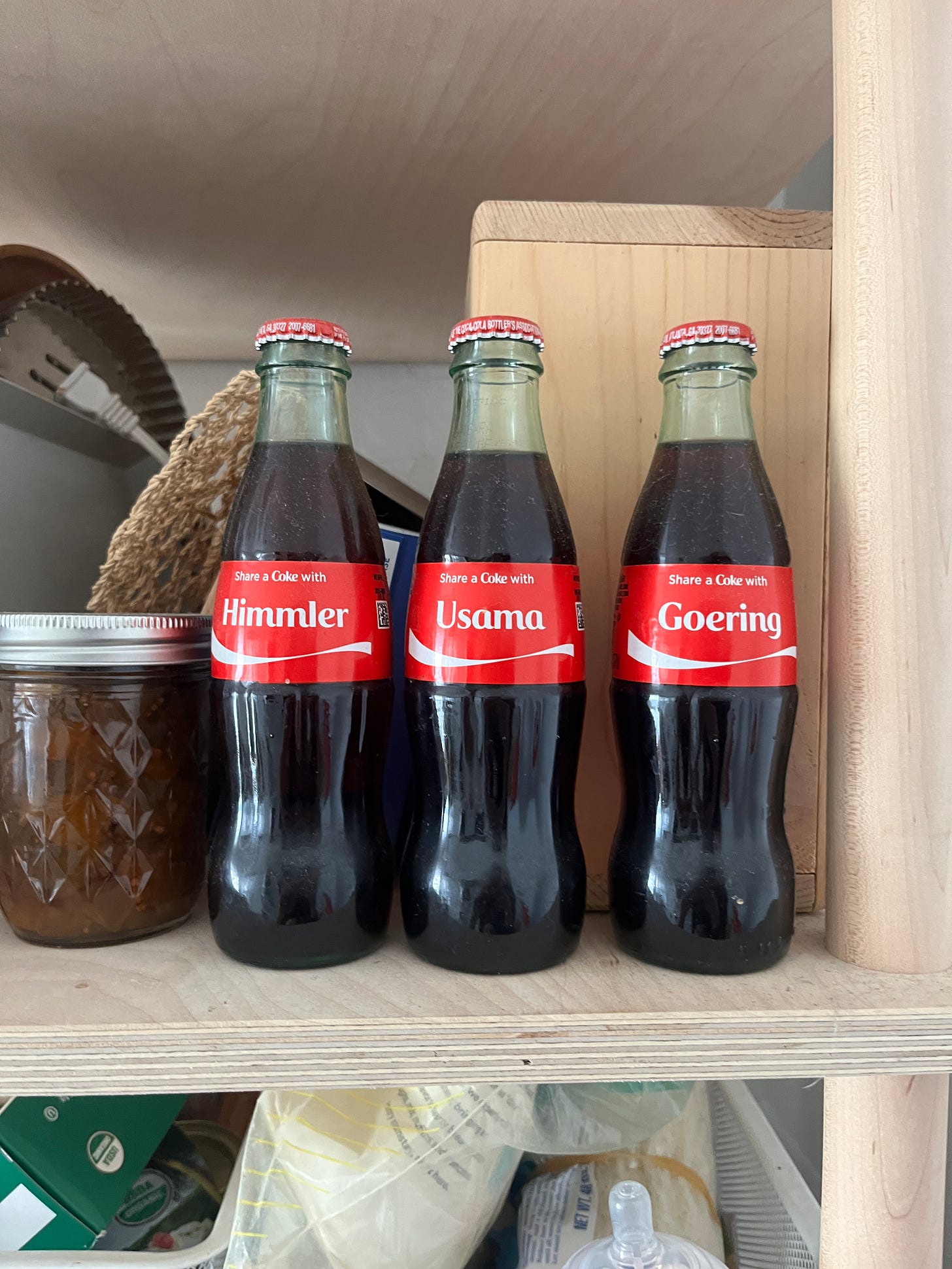

In the latter category are three full eight-ounce glass bottles of Coca-Cola sitting on the shelving above our fridge:

These bottles, which feature custom labels exhorting the drinker to “Share a Coke with,” respectively, Himmler, Usama, and Goering, have been moving around the apartment since 2015, climbing, with the help of my wife, to increasingly further-away reaches of shelving and storage. Why do I hang on to them? They are not objects to which I have a particular sentimental attachment. Nor are they useful, or valuable, or even funny enough to be worth keeping in order to, I don’t know, show off at dinner parties (???). No: If I am being honest, I have been keeping these bottles of Coke because I bought them for a blog post I meant to write but never did. I now realize that in order to dispose of them, I must write that blog post. Or a blog post, at least.

So I’m going to explain why I had these bottles printed, but before I do that I need to warn readers that the story that follows, if it can be called that, is neither interesting nor educational, and has no moral or punchline. I am not relating this story because I think it is a gripping or revealing narrative or that it illuminates some point. I am writing this down because I do not want to make room in my new home for eight-ounce bottles of Coke with the names of high-ranking Nazis, and I need to write the story of those bottles down in order to release myself of the obligation to keep them.

In 2015, Coca-Cola ran an ad in the Super Bowl with the premise that the internet is horrible (agree) and if the internet drank coke (??) all of the mean posts would become nice (???).

As these things go it was neither egregiously insufferable nor particularly memorable. However, the ad itself was accompanied by a gimmick whereby the official Coca-Cola Twitter account would “make hate happy” by transforming mean tweets into cutesy ASCII art if you replied to them with the hashtag #makeithappy.

Back then I was working at Gawker with an extremely talented but sadly quite disturbed troll named Caity Weaver, who realized that this campaign allowed anyone on Twitter to essentially force the official Coca-Cola account to tweet whatever they wanted. She experimented by tweeting the infamous White Nationalist slogan “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children” at Coca-Cola along with the hashtag #MakeItHappy, and, lo, the Coca-Cola Twitter account parroted back “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children,” in the peppy shape of a balloon dog:

At the time Gawker’s governing editorial philosophy revolved around plowing resources into the stupidest possible ideas, so we enlisted Adam Pash, the director of Gawker Editorial Labs, to build a bot that would tweet the opening of Adolf Hitler’s autobiography Mein Kampf at Coca-Cola, line by line, and add the hashtag #makeithappy. After a half day or so of doing this, I wrote a post called “Make Hitler Happy: The Beginning of Mein Kampf, as Told by Coca-Cola”:

"Make it happy!" Coca-Cola's new marketing campaign exhorts. The campaign, introduced during a Super Bowl commercial, is accompanied by a stunt through which Twitter users reply to negative tweets with the hashtag "#MakeItHappy"; Coca-Cola then transforms those tweets into cute ASCII art. "We turned the hate you found into something happy," @CocaCola chirps.

The Twitter stunt poses an interesting hermeneutical question. Below, for example, you will see the official Coca-Cola account tweet "We must secure the existence of our people and a future for White Children."

(Here we embedded the tweet screen-shotted above.)

This, the fourteen-word slogan of white nationalism, seems "off-brand" for Coca-Cola. But there it is, on its Twitter account, plain as day. Even when the text is shaped like a dog, it is disconcerting to see Coca-Cola, the soda company, urge its social-media followers to safeguard the existence and reproduction of white racists. Is Coca-Cola a white nationalist organization? Its Twitter says: Yes.

It's true—we asked Coca-Cola to tweet about its concern for the continuing existence of the white race. But this is not particularly different from asking for a retweet from a brand or a celebrity. If we asked Coca-Cola to retweet, for example, the first four paragraphs of Hitler's autobiography Mein Kampf, would it?

As it turns out, yes. Gawker Editorial Labs director Adam Pash built us a bot to tweet the book line-by-line, and then tweet at Coke to #SignalBoost Hitler and #MakeItHappy.

Was there a point to doing this? Well, yes: The first-order point was that it was funny. The second-order point was this was a stupid, condescending ad campaign, a product of a corrosive commercial value system that insulted our (that is, soda consumers’) collective intelligence, and we had a kind of moral obligation to insult it back.

But, again, the main point is that it was funny to make the Coca-Cola company tweet passages from Mein Kampf in the shape of various ASCII cartoons.

Both points, we felt, were confirmed when Coca-Cola ended the bot promotion and took down the tweets. But we were nevertheless somewhat surprised by the angry reaction from the advertising trade press and a wide variety of onlookers on Twitter. Sam Biddle summarized the response (in a post I’ll get to in a moment):

Human beings—including journalists—flocked to Coke's side. The Verge sobbed that we'd "ruined" Coke's "courage and optimism," AdWeek called our work a "debacle," and Coke itself feigned dismay: "It's unfortunate Gawker made it a mission to break the system, and the content they used to do it is appalling." "Have a Coke and a—frown," bleated some dunce at USA Today. Coca Cola's rough approximation of humanity had made an enormous impression, and its drinkers and friends took a stand. No more, they tweet-chanted in unison, no more unkind words for this maker of sweet liquid toxins.

At the time I was shocked that people who were not professionally invested in the marketing operations of the Coca-Cola company had an emotional stake in the success of this advertising campaign. Now, with the benefit of hindsight, and the emotional maturity/stability I have developed in the interceding years, I can say: LOL! OK! Whatever!

Either way the real problem for me was professional, because the post had pissed off the people who sold ads for our website. My sense, in retrospect, was that every post we did pissed off Gawker’s ad-sales department,3 but this post in particular was seen as beyond the pale, I suppose because it indicated in a relatively explicit fashion the contempt with which we on the editorial side held advertising as a concept, despite the fact that, or maybe because, it was “the whole business model of our publication.”

Gawker as an institution was good about maintaining a firewall between advertising and editorial, but this was only a few months after an organized campaign of teenage shut-ins attempted to put us out of business by calling for an advertiser boycott, and things between ad sales and editorial were still tense. At the same time, the company was subject to a number of strangely persistent and well-funded lawsuits. We would later learn these were being funded by the Facebook board member Peter Thiel, but at the time, given that they appeared to be unrelated, they had the effect of convincing the business side of the company in general, and especially its founder and CEO Nick Denton, that the editorial side was irresponsible and out of control.

So Nick suggested we write a sort of defense of the stunt, if only so that he could come argue with us in the comment section. The idea, if I remember it right,4 was that Nick felt that if he publicly defended the concept of advertising, and chastised us for being childish, it would cheer the put-upon ad professionals who worked at the company.5

The result of this suggestion was the post of Sam’s that I quoted above, “Brands Are Not Your Friends,” which articulated at greater and more specific length one key point of the original prank:

People tend to talk to brands on the internet like they might have lost their virginity to them. They very well may have—an empty bag of @Doritos under the mattress or in the parking lot of a @McDonalds—but it's a one-way relationship. Your sister's face has never appeared on a highway billboard, but Nestlé and Burger King and motherfucking Denny's show up in the same streams as your loved ones.

This is the business model of the social web. Someone has to pay for the services we use to keep in touch with our friends, after all. On Facebook, the button to "like" a brand (like a brand!) is functionally identical to "liking" another person. The vast, awful landscape of Brand Twitter has become a playground for social media managers to act like virtual tweens. The prevailing online marketing strategy for brands in 2015 is to blend in with the children, become just another bae to fave and retweet.

It shouldn't have to be said out loud to sentient human beings that this is bad. But it is. It is sinister and bad and says a lot about how we have collectively lost our minds as a species. I'm afraid and sad for everyone.

Sam’s post remains to me some of the best and truest writing of that era of blogging, and the blunt headline still echoes around the cobwebs of my brain. (I thought about it recently, for example, when the Financial Times reported that brands--hailed in November for walking away from Twitter--had been given the green-light to return by ad conglomerate GroupM, even as the site and its owner grew more vastly more unbearable.)

Anyway, if I remember right Nick did show up in the comments,6 and we did fight with him there a bit, but thankfully for everyone involved, even Hitler, the entire comment database of Gawker disappeared sometime after Bustle Digital purchased the website at auction in 2018. In any event, everyone--Caity, Sam, Nick, the ad-sales department, and presumably the fine people at the Coca-Cola beverage firm--moved on.

Except for me. The episode had activated my inner reserves of petulance, which are vast. I no longer cared so much, if I ever really did all that much, about the smarminess of the Coca-Cola ad campaign or the hellishness of brand internet. I was angry that we had been obligated, for whatever reason, to defend ourselves over a post whose entire point was to be stupid, funny, and more or less indefensible.7 So I did what any self-respecting little brat would do, and tried to be as annoying as possible about the Coca-Cola Company whenever I could.

When, for example, the Coca-Cola Company celebrated the 75th anniversary of the German soft drink Fanta with a video that described the year of Fanta’s birth (1940) (again, in Germany) as “the good old times” with a video about the history of Fanta that somehow managed not to mention Nazis, I wrote a short post that no one read but that satisfied me:

"Resources for our beloved Coke in Germany were" indeed "scarce," because Germany was at the time in the midst of an violent and terrifying advance to spread its genocidal empire across Europe, and the United States had enacted a trade embargo against it. Why would Coca-Cola refer to such a period as "the good old times"? Possibly for the same reason it recently tweeted the opening of Mein Kampf from its official Twitter account: Because it is a clumsy, stupid corporation constitutionally unable to reckon with history, irony, or morality, and, thanks to its congenital sociopathy, incapable of instilling in its employees a sense of ethical duty or purpose. And also because it loves Hitler.

And when--you can see where this is going--Coke offered the ability to order glass bottles with custom “Share a Coke with” labels, I sprang into action. They had wised up since February and would not let me order a Hitler Coke, but Goering and Himmler were available. And I was blocked from ordering one for Osama and had to settle for Usama, which is the same name but less funny.8

Unfortunately, around that point, my career at Gawker suddenly ended when [INAUDIBLE DUE TO TAPE DAMAGE]. A few days after I left, my friend Jim Cooke (who designed the incredible logo for this very newsletter) brought them to me at a bar where we were all drinking, and I brought them home from there, intending to eventually, someday, write a blog about it.

And there you have it: That is why I have a “Share a Coke with Himmler” bottle on my fridge. As a tribute to a minor episode of being annoyed, and being annoying, in my career.

I recognize that this is an abrupt and likely unsatisfying ending. But I would argue that this is the appropriate way to end a story with no narrative shape, no clear stakes, an only semi-comprehensible moral-political sensibility, and an extreme over-reliance on vague memories of relatively internecine office politics around a series of minor incidents eight years ago.

Is there a lesson here? Maybe something like, “every object has a story, but the story is not always that good, even if the object is on its face kind of weird.” Or “isn’t it funny how with the benefit of hindsight, all those grudges you held and fights you picked at your old job turned out to have been totally justified.” Perhaps the lesson here is that we all have our own personal “Himmler Cokes,” except I’m not really sure what the metaphor would be there. Perhaps the lesson is simply “Brands are not your friends,” though I certainly do not feel anyone who needs to has learned that lesson since Sam first attempted to teach it in 2015.9

The truth is that none of that really matters. What matters is this: I have, by relating this story, released myself of the obligation to keep these Coca-Cola bottles. Now I am left only with the lingering question “can you drink eight-year-old Coke?”

On a related note, I enjoyed this Joe Wiesenthal newsletter on the subject of the Zoom earnings calls.

Thank you in particular to the subscriber who emailed a photo of his cap perched atop a Storz and Bickel “Volcano” vaporizer next to an overturned bowl of shake and underneath a mounted Sony Minidisk player with velcro-attached remote--a incredibly tribute to vibrant culture of the “Read Max community.”

As far as I can tell the ideal version of Gawker as far as ad sales was concerned was a blog that only posted brand-friendly stories, and if that could not be accomplished, then simply a version that never posted at all.

It would also mark a demonstration of the capabilities of “Kinja,” the new content-management system that was supposed to encourage scintillating debates and discussions, like “a digital media CEO and one of his employees debate whether it was mean to make Coca-Cola tweet part of Mein Kampf.”

I have this memory that Nick actually said in one comment “Brands are your friends,” but that might be completely invented in my head. ETA: Thank you to Andy Orin and Keenan Trotter for sending me Nick’s original comment, preserved on the internet archive. You can read it yourself here; strong stomachs only.

“Never apologize, never explain” is bad moral-ethical practice but it’s pretty good editorial advice. Any successful publication creates its own audience in part through implicit litmus tests: Do you find this funny? Important? Worthwhile? If you’re good enough you can trust that audience to understand what you’re doing without needing to defend it.

To the extent that I have any regrets about this lengthy story it’s that I went for “Usama,” which simply doesn’t hit the way Himmler and Goering do. Surely if I had thought more I could’ve come up with a funnier name, and one more clearly on the Nazi theme.

Except the Read Max brand.

The lesson here is your wife is a saint. -Sent from your wife

Ur insane lol