Greetings from Read Max HQ! In this week’s newsletter

Trying to outline an emerging debate about A.I. and writing that involves defending LLMs as “democratizing” tools; and

an open question: What is “industrial” sci-fi?

A reminder: Read Max exists at the pleasure of its loyal paying subscribers, whose support enables basically the whole structure of this stupid newsletter. For every newsletter I spend hours reading, thinking, procrastinating, writing, deleting, procrastinating, writing again, and procrastinating more, and it’s the incredible generosity and belief expressed by paying subscribers that allows that process to recur each week. This newsletter costs about the same price every month as a beer; so if you get monthly “I’d like to buy him a beer”-level satisfaction out of it, please consider signing up:

The war over A.I. writing

I don’t personally, at this point, have a settled or clear philosophical opinion on A.I., art, and creativity. But many other people do! Some related conflicts have emerged this week about the meaning and stakes of using generative A.I. apps like ChatGPT in creative writing (and other kinds of art), and I want to take note of where the lines are being drawn, because I think the arguments being made are interesting and revealing.

The discussions and arguments I’m thinking about have been kicked up by two pieces of writing this week; the first is Ted Chiang’s New Yorker piece “Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art,” in which Chiang argues:

The companies promoting generative-A.I. programs claim that they will unleash creativity. In essence, they are saying that art can be all inspiration and no perspiration—but these things cannot be easily separated. I’m not saying that art has to involve tedium. What I’m saying is that art requires making choices at every scale; the countless small-scale choices made during implementation are just as important to the final product as the few large-scale choices made during the conception. It is a mistake to equate “large-scale” with “important” when it comes to the choices made when creating art; the interrelationship between the large scale and the small scale is where the artistry lies.

For whatever it’s worth, this isn’t my favorite piece that Chiang has written about A.I.--I feel resistant to categorical statements about “art,” especially when they rely heavily on an idea of “the human.” But I am somewhat less interested in the specifics of Chiang’s argument here than I am in a particular kind of response. Martin Pilchmair’s objection, published at his Substack, is largely about Chiang’s characterization of art, but there is a passage that stuck out to me:

I don’t want to concern myself with a text that forbids artists to work in a specific way. The same text has been written by the same people when electric guitars, mobile phone cameras, video games, books, and any other new medium came along. There will always be a gatekeeper.

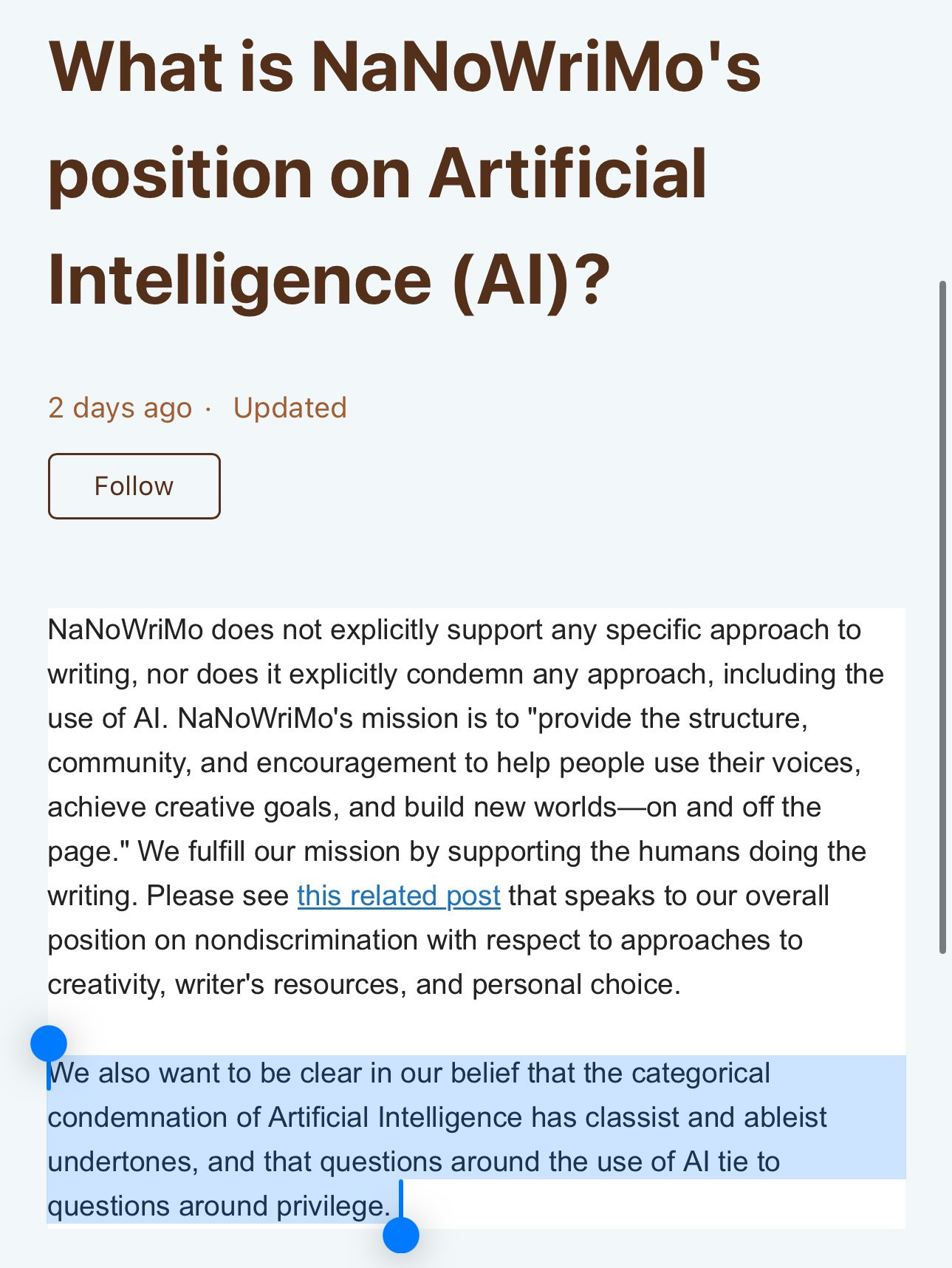

This characterization of what Chiang is doing (“gatekeeping”) struck me because of the other piece of writing this week that’s become a magnet for conflict: A statement by the official organization overseeing the longtime internet tradition “National Novel Writing Month”--an annual “event” in which participants, many or most of whom are not professional writers, attempt to write an entire novel over the course of a single month--establishing its “position on A.I.” The statement has been updated and clarified, but the original remains on Twitter:

This statement got a lot of attention and criticism--specifically the bit about how “the categorical condemnation of Artificial Intelligence has classist and ableist undertones, and that questions around the use of AI to questions around privilege.” I agree that this is a silly thing to say, but I also think it’s an interesting framework in which to couch a defense of the use of A.I. in writing! A longer post from Cass Morris, a former member of the NaNoWriMo authors board, condemning the statement, also featured this interesting snippet of an email from NaNoWriMo’s Interim Executive Director:

And, in any case, we don't think we should be legitimizing certain ways of writing and authoring and delegitimizing others. In a separate post, we talked about harm done historically to writers by other writers who delegitimized their methods.1

Between these various statements and responses you can see the outlines of a particular kind of A.I. apologism: LLMs are a tool for democratizing writing; disparaging or forbidding them is a form of gatekeeping designed to delegitimize and exclude outsiders from participation.

It’s pretty easy to scoff at people making this defense of A.I. But I think it’s correct, sort of. Where the LLM apologists say “democratizing” I might say “deskilling,” and where they say “gatekeeping” I might say something like “labor action” but we mean more or less the same thing: Increased avenues for participation are likely to drive down the price of labor. Other workers “gatekeep” all the time: In the building trades they do it with unions; barbers and descendent professions like doctors use professional licensing systems; the only tools left to writers, who (with a few narrow exceptions) have no legal way to control and negotiate the supply and pricing of their work, are indirect forms of social protectionism: snobbery, taste, and “gatekeeping.”2

I’m joking here--NaNoWriMo participants are not at the present a real threat to the value of writing work--but only kind of. I suppose my point is that being anti-LLM is a kind of gatekeeping, and in the abstract that’s fine, and is in fact is an important way for writers to protect themselves.

The flip side, though, is that this protectionism generally occurs along the same contours of power that structure the rest of the world--which is to say that poor and working class people are likely to be already “excluded” from the category “writer” for a host of not-even-A.I.-related reasons--and because of this fact “gatekeeping” is a rhetorically powerful and generally persuasive concept to deploy against it.

Indeed, this exact debate should be pretty familiar to us at this point, both in the specific context of writing online--as a blogger and journalist, I’m intimately familiar with the “democratization”/”de-skilling” double-edged sword--but also in the context of “the software industry” in general, which since the advent of the commercial internet has specialized in coming up with profitable new ways to loosen labor markets and cheapen work under the ideological cover of flexibility, independence, and especially access. As the academic Sarah Brouillette put it on Twitter, “platforms don't care where the content comes from and learning the craft of writing is incidental ... they want it in volumes and telling people that traditional publishing is exclusionary is (1) correct and (2) a great way to extract content.” (Brouillette is apparently writing an extremely interesting-sounding book on this topic.)

Anyway, I still don’t really have a strong opinion on whether or not LLMs can or will ever create “art.” But I suspect they will overall and ultimately be quite bad for writers in their capacity as fairly compensated workers, while being probably irrelevant to writers in their capacity as “artists”!

What (and where) are the industrial science fiction movies?

I caught Alien: Romulus recently and mostly enjoyed it--there’s a Stupid Thing the movie does, but aside from that Stupid Thing, it’s not really too lore-heavy, and while it’s sometimes a little clunky and obvious, so too are all the Alien movies besides Alien. One thing I appreciated about Romulus was its redirection of the franchise away from the paranoid cosmic-existential concerns of the previous two installments, Prometheus and Alien: Covenant (both of which movies I love, to be clear!) and back toward the grimy, sooty industrial milieu of the original Alien.

But it also made me wonder: What else qualifies as “industrial” sci-fi? Lots of sci-fi movies (here’s a good list on Letterboxd) make use of a kind of “industrial” aesthetic--grime, soot, big honkin machinery--but very few of them actually show or involve industrial work or workers. In fact, many of these movies (1984, Brazil, even Children of Men to some extent) are actually about bureaucrats or other kinds of service-sector “knowledge workers”; others (Aliens, Soldier, Blade Runner, Alien^3, Pitch Black) may mention industrial occupations (mining, usually) but the actual industry occurs off-screen (and, indeed, off-planet), and the main characters are generally soldiers or attached to the carceral complex as cops or prisoners.

All of the movies I’m listing are quite good, to be clear, and it’s necessarily hard to imagine a futuristic manufacturing economy, especially if you start from the assumption that sophisticated robots can do all the work. This might be why the industry most often depicted in “truly” industrial sci-fi (by which I mean sci-fi that’s actually “about” industry and workers) is resource extraction. Alien, of course, is about a tugboat crew pulling a mile-long refinery packed with mineral ore; there’s Outland, a sort of space western starring Sean Connery as a marshal at a mining colony on Io; Roland Emmerich’s Moon 44 is about a combination prison-mining complex. (There’s Total Recall, too, though the Martian mining feels slightly beside the point; and Empire Strikes Back, but you never see the actual mining taking place on Bespin.) You could quibble with any of these, of course (what is the class position of space merchant marines?), but they are each concerned with the substance of industrial work and workplaces.

But as for sci-fi about or featuring industrial manufacturing, there’s, well, Metropolis… and then, what, Elysium? Snowpiercer? What am I missing? This isn’t really a complaint; just an observation. Without getting too deep into it, it seems like a lot of the movies that come immediately to mind as “industrial” sci-fi are better thought of as “post-industrial” sci-fi, which is to say sci-fi about worlds marked by the aftereffects of industrialization (social atomization, atmospheric pollution, wealth inequality) but without even the economic growth and stability industrialization promises. Which probably shouldn’t be surprising!

It’s not surprising to hear this specific argument about A.I. coming from NaNoWriMo, which is, more than anything else, a community and gathering space for non-professional and outsider writers.

Responding to (believe it or not) a different writerly kerfuffle on Twitter, Kate Wagner makes a similar point:

if you view writing as labor, the stakes of things like AI (and, to name another common topic of debate rn, men who keep women from doing their creative work) become clearer without wishy washy bourgeois debates about individual talent or artistic ritual or "ways of being." all these essays are about why WE think art is different and unique and should be protected as this sacred thing. I'm sorry but the people who run the economy and are willing to crush anything in their path do not care. there is nothing you can write that will make them care. we are talking about alienation. we are talking about the same deskilling that workers in other fields have experienced for some 150 years. i know that sounds like it's undervaluing art, but it's the way these technologies are viewed by their own architects.

Though I’d add that essays “about why WE think art is different and unique and should be protected as this sacred thing,” of which Chiang’s is one species, are maybe less irksome if you think of them as elements of a “gatekeeping” strategy for protecting the worth of creative labor, even if they are in substance wrong.

I find these debates a confused and largely misguided. The answer to the question "can A.I. create art" is "no" in a definitional way, but this question does not have the economic or cultural stakes it is imagined to have. It's very much like asking "can a machine create handmade goods?" The fact that the answer to this question is "no" had very narrow implications for the transformations wrought by the Industrial Revolution.

The example of photography is illustrative here. Chiang revisits the debate about whether photography is art, and take some pains to explain why we decided that it is and reconcile that stance with his stance on A.I. But how much does that matter. The vast majority of people who would have hired someone to paint their portrait before the advent of photography now hire a photographer to take a picture, or take a picture themselves. Do they ask themselves whether the photographs are art? Do they care? No, because for them, the function of the portrait, painted or not, was not especially related to whether it is art. This is true in many domains in which paintings and photographs are substitutes.

Similarly, someone looking for something to put on in the background as they work or exercise is not primarily looking for art, though art can serve that function. Same with someone sitting down in front of their TV after work or someone reading a novel in bed before they fall asleep or looking to fill wall space in their apartment.

Somewhat more controversially, but for related reasons, I also think the question "will AI ever make works indistinguishable from human art" is also less important than it seems. How many times have you looked at a photograph and been disappointed that you can tell that's not a painting?

In the specific example of NNWM, the statement undermines what NNWM is: Can you - Y.O.U. - write 50,000 words of original fiction in one month?

I could probably win a marathon if I was on a segway the entire time. It ruins the entire purpose of the marathon. Having a segway marathon would be stupid and boring.