The coming pro-smoking discourse

Predicting a future for takes

One way of thinking about this newsletter (Read Max) is as equities analysis for the discursive marketplace, answering important questions for the armchair take trader: What discourses have peaked? What concepts should you short? How are you balancing your take portfolio?

My longtime professional and personal experience as a poster has left me adept at seeing the hidden structures that lurk behind the peaks and valleys of “the discourse”; paid subscribers in particular are well-positioned to profit from the insight offered by Read Max’s sophisticated and proprietary models.

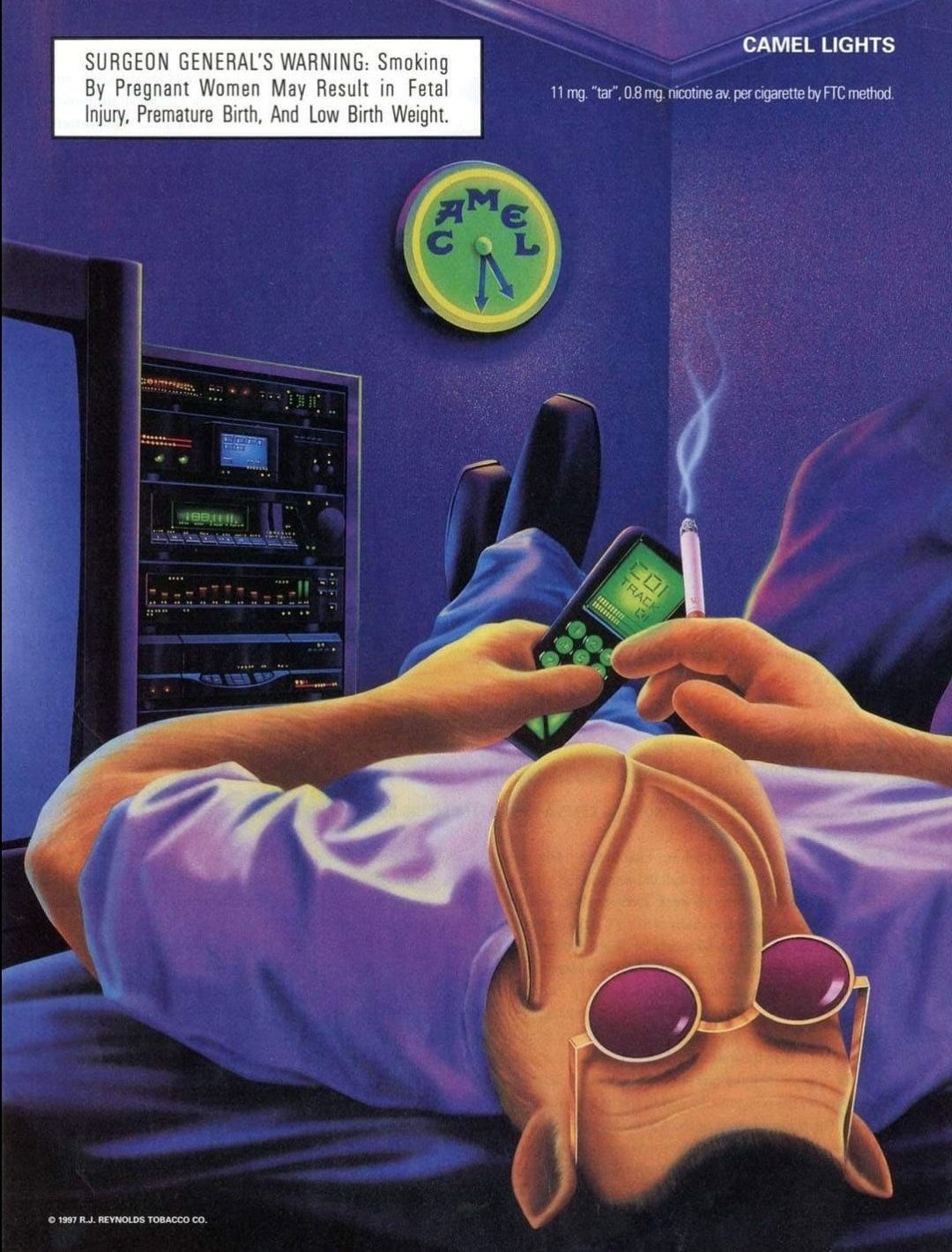

For a while now, Read Max analysts have been intrigued by what is often called on Twitter “smoking discourse,” as in “cigarettes.” Now, following certain recent events on Twitter, we’re prepared to advise clients that we believe strong “pro-smoking” positions grounded in socio-political identities are poised to have a “moment” soon. Our analysis indicates that certain structural factors are in place to encourage arguments like “smoking is good for society, actually” and “anti-smoking laws are bad science/policy” to move past “trolling” and be adopted as common sense by a loose confederation of IDW Substackers, trad nutritionists, and downtown cool kids, building on the ties formed between these groups around the COVID-19 pandemic.

Disclaimer

The hypothetical pro-smoking movement described below is a prediction based on our proprietary analysis, not a description of the current moment. This is not investment or medical advice. Read Max is not offering a strong opinion on whether or not smoking is good for you (it’s not) or whether or not sometimes you just need a cigarette (you do) or whether or not it looks cool (it does).

Why now?

Two weeks ago the actress Jenna Ortega, star of the Netflix show Wednesday, was filmed smoking a cigarette, sparking a multi-day rally in smoking discourse on Twitter. From our perspective the peak of this discourse was the following tweet:

This tweet is what professionals call a “shitpost,” or “bait,” i.e., it is a “dumb joke” and not an earnest expression of beliefs. Nevertheless its top-tier numbers lead us to the unavoidable conclusion that pro-smoking content is good for engagement in key discursive marketplaces such as Twitter. (Including, and maybe especially, pro-smoking content from an ostensibly left-wing, class-conscious perspective.) This kind of open opportunity for finding engagement is rarely left unmet, and based on historical trends, we believe that a strong, formally pro-smoking bloc has a high likelihood of emerging on Twitter, Substack, and other markets within the next year.

Historical background

“Pro-smoking” positions among are, of course, nothing new; the former Harper’s editor Lewis Lapham is a notorious pro-smoking advocate. It’s a position particularly appealing to contrarians, and, like many contrarian arguments, can veer quite quickly from “vaguely intriguing” to “impossibly boorish.” Here, e.g., is Christopher Hitchens paraphrasing an entertaining argument that the end of widespread smoking killed literature in an LRB piece from 1992:

Kiernan’s sweetest note is struck when he contemplates the wondrous effect of tobacco on the creative juices. Having reviewed the emancipating influence of a good smoke on the writing capacities of Virginia Woolf, Christopher Isherwood, George Orwell and Compton Mackenzie, he poses the large question whether ‘with abstainers multiplying, we may soon have to ask whether literature is going to become impossible – or has already begun to be impossible.’ It’s increasingly obvious, as one reviews new books fallen dead-born from the modem, that the meretricious blink of the word-processor has replaced, for many ‘writers’, the steady glow of the cigarette-end and the honest reflection of the cut-glass decanter. You used to be able to tell, with some authors, when the stimulant had kicked in. Kingsley Amis could gauge the intake of Paul Scott page by page – a stroke of magnificent intuition which is confirmed by the Spurting biography, incidentally; and the same holds with writers like Koestler and Orwell, depending on whether or not they had a proper supply of shag.

Kiernan suggests that both Marx and Tolstoy may have suffered irretrievable damage as writers from having sworn off smoking in late middle age; he has no difficulty in showing that Pavese also experienced great challenges to his concentration from trying to give up, and that poor old Charles Lamb (who took up smoking while trying to give up drinking) was stuck miserably, like the poor cat in the adage, between temptation and abstinence, to the detriment of his powers.

That’s a sort of interesting argument, if you squint, but to get to it, you have to read stuff like this:

Smoking is, in men, a tremendous enhancement of bearing and address and, in women, a consistent set-off to beauty. Who has not observed the sheer loveliness with which the adored one exhales? That man has never truly palpitated. It is the essential languor of the habit which lends it such an excellent tone in this respect, as Oscar Wilde understood so well when he described it as an occupation. Kiernan thrills to his own description of Greta Garbo blowing out a match in The Flesh and the Devil, and vibrates as he recalls Paul Henreid taking a smoke from his own lips and passing it to Bette Davis (Now, Voyager). With approval, he cites the mass meeting of young women at Teheran University; every pouting lip framing a cigarette in protest at a Khomeini fatwah against smoking for females.

Oh, brother. This “intellectual” pro-smoking position has never been able to find a foothold in the wider discourse, due to material conditions outside of contrarian writers’ control (i.e., editors’ desire to only run one pro-smoking article every few years, and the recently disproven belief that there was not a large audience with a constant appetite for performances boorishness). Only now, with the rise on social-media platforms of certain new political and social formations that are open to the production of pro-smoking discourse, can it solidify into something more than a columnist’s “riff.”

Components of the argument

This is speculative, but we believe the broad strokes of the argument will be something like this:

Nicotine is a creative and intellectual stimulant in an age of mid cultural production.

Smoking is a social activity in an age of platform-warped anti-sociality.

Cigarettes are an acceptable danger in an age of “safetyism” and fear.

Banning things is ”neoliberal paternalism” that targets the “marginalized communities.”

The pro-smoking coalition?

We believe, based on structural analysis of political/affective affinities and vibes, the potential pro-smoking coalition to consist of three pillars:

The loose grouping of contrarian intellectuals and anti-woke elites sometimes known as The Intellectual Dark Web;

Cool downtown art and scene kids; and

“Trad” health and lifestyle influencers.

What do these three groups have in common? A contempt for mainstream elite liberalism, and, more specifically, a contempt for public-health policy.1 Despite their differences, these factions already formed loose bonds of allegiance and began to overlap during the COVID-19 pandemic, largely around their shared contempt for various public-health measures; now that organized anti-COVID campaigns have all but ended, anti-smoking policy and rhetoric provides an attractive new oppositional target.

1. The Intellectual Dark Web

Recently, in the midst of a wide-ranging interview, Tablet editor David Samuels and neoconservative defense analyst Edward Luttwak discussed the societal benefits of nicotine [bolding mine]:

Samuels: Why do educated people believe in obvious stupidities like the crushing power of hybrid warfare in such a herdlike way? A big reason of course is class interest—they are getting rich off it. Now there is also the role of Twitter and other networked social platforms in reinforcing the dominance of the mass mind, and punishing dissenters from the consensus from which everyone else is making money.

A reason that is less well-explored, I believe, is the West’s war on nicotine. The massive brain outages we see throughout the West, and particularly in America, are in no small part due to the war on smoking, which both makes people smarter and kills them before they become senile.

Luttwak: Absolutely. One book I’ve never written, is “The Impact of the Arrival of Nicotine and the Scientific Revolution.” A big jump in intellectual achievement that took place among Europeans, all of whom smoked. The social history of nicotine begins with the sharpening of the brain. I stopped smoking long ago but still I miss it. […] An easy remedy for the stupidity of mankind is to go back to nicotine.

I am captivated by the tone and breadth of argument here,2 but for our more narrow purposes I want to underline two key components of Samuels and Luttwak’s argument, to wit:

Smoking is good for society as a whole, and

Cigarettes are bad for you and actually that’s good.

This is extremely advanced public-policy contrarianism of the kind that is difficult for even professionals to resist.

2. Cool downtown art and scene kids

Also last year, The New York Times Style section published an article arguing (in its sub-headline) “Cigarettes, once shunned, have made a comeback with a younger crowd who knows better.”

It should be made clear that the piece offers no statistical evidence that cigarettes are making a comeback, despite a valiant effort to find a single academic who will play along. (Like all classic trend pieces it is no less enjoyable for relying on some extremely conditional assertions, such as “If the clouds of smoke many of us think we’re seeing are not, indeed, mirages, the next logical question is to ask where they’re coming from.”) Nevertheless, and importantly for understanding the discursive position of smoking, the article establishes that cool young people are smoking and defending in various incoherent but charmingly pretentious terms:

“Part of it is that it almost feels like rejection of wellness culture, which is very stupid,” she said. It feels good, she said, to reject all that.[…]

So did Emile Osborne, a 22-year-old graphic designer. “I switched back to cigarettes because I thought it would be healthier than Juuling,” he said. “Cigarettes seem like a known evil, whereas vaping you don’t know the side effects at all. I can go out for a cig a few times a day. It’s a break from what I’m doing. That’s my nicotine fix for the day.” […]

“Beautiful people do it, really talented people do it,” said Ms. Amis,3 who lives on the Lower East Side. “It goes with things that I admire.” In fact, back in college, she wrote a little manifesto about smoking titled “Notes of a Neo-smoker,” which included missives like: “Smoking is the epitome of masochism,” and “It is a joy to be contemporarily atypical.”

3. “Trad” health and lifestyle influencers

Finally, we believe certain lifestyle influencers have a strong likelihood of promoting smoking within the next few months. Various anti-establishment, trad-life nutrition influencers already praise nicotine as a “writer’s nootropic,” though in general they suggest gum, patches, or pouches. We believe that some influencers in this highly competitive sector will adopt “smoking is good for you” as a way to differentiate themselves in a crowded marketplace. Here, e.g., is Andrew Tate, an inconsistent but important indicator for trends in reactionary lifestyle content:

Summary

I reiterate: This is a prediction based on our assessment of current trends in the discourse. The high-alpha nature of committed, political “smoking is actually good” arguments, combined with existing coalitions for developing annoyance at people with public-health masters degrees into ideological position, is likely to create a solid pro-smoking bloc, especially as we enter summer and face down a fertile period for stupid discourse.

And, maybe even more specifically than that, a contempt for well-meaning but admittedly extremely annoying MPHs on Twitter

I want to make sure readers appreciate the head-spinning magnificence of Samuels’ question, its framing, and its structure--to move from “hybrid warfare” as an object of “herdlike belief” (???) to a crank complaint about Twitter to “the West’s war on nicotine” (!!!) in so few sentences is majestically bird-brained.

This is, of course, the daughter of Hitchens’ great friend Martin Amis.

It fits into the cultural zeitgeist of revisiting and romanticizing the early 90s when smoking was taking its last gasp of cultural relevance. I am very much looking forward to American Spirits, loose jeans, baggy flannels, and music with guitars taking back their rightful place at the center of the cultural universe.

I read this article to my husband on our post-work smoke break, and he wants you to "stop speaking this into being" and to "step away from the Lathe of Heaven"