One of the quintessential experiences of the contemporary web is seeing something not quite right flit across a feed and disappear without explanation. Inexplicable ads, incomprehensible posts, disturbing chumbox images: Your attention is not necessarily fully drawn to these content units, but your continued exposure to them builds up, in the back of your mind, an uncomfortable sense of disorientation and irreality -- the way shadowy movements in the corner of a frame of a good horror movie slowly congeal into an overwhelming and almost inexplicable dread. Only, online, instead of a ghost, it’s a fake poster for a fake sequel to the (real) 2013 Jennifer Aniston comedy We’re the Millers, being shared to 70,000 enthusiastic comments on Facebook. Or an inexplicable legion of identical storefronts advertising bizarre gadgets. Or whatever. (More on both of these examples shortly.)

Solving, or at least attempting to solve, internet mysteries is one of the Pillars of Content of the newsletter you are currently reading1, and from time to time I try to follow these particular deformed rabbits down their holes. Readers enjoy satisfying accounts of otherwise inexplicable online phenomena; I enjoy the opportunity to package and monetize my own curiosity, paranoia, obsessiveness, etc.

But where “solving” certain kinds of internet mysteries is as simple as researching and synthesizing a ubiquitous scam, or calling up a strange guy on the phone, there’s a certain kind of mystery that’s impossible to satisfyingly solve. These are mysteries where there isn’t some novel geopolitical formation to blame, or weird guy to call on the phone -- mysteries where the answer, is, basically, “this is just how Facebook/Twitter/YouTube/Google/Alibaba/etc. works.” (I mean, for this kind of thing there probably is a guy you could call somewhere, but the problem is that he’s almost certainly not weird, or markedly criminal, or markedly anything at all -- he’s just a guy [of any gender] operating fully rationally within the parameters of a really fucking big and really fucking weird system.) I poke around, I find weird efflorescences and byproducts of platform economies and capitalist logistics, I save a bunch of bookmarks, but the rhetorical or factual button that would make it feel like a complete newsletter eludes me.

Anyway, I’m never quite sure what to do with these little semi-solved mysteries, evidence and material for which occupy tabs and bookmark folders and notes in my browser for months. An incomplete story can’t sustain an entire newsletter. But maybe two incomplete stories can? In an effort to exorcise these little mysteries from my browser (and the back of my mind), I’m going to dump some collected material on two stories I started reporting but never felt like I had enough to write about.

Take, for starters, this tweet, which a friend sent to the group chat a few weeks ago:

“Is this real?” another friend2 wondered. I’m not entirely sure what he meant by that question, but I can confirm that the Facebook post seen in the tweet, published on the page “Upcoming Movies,” is real, while the poster itself is not.3

The Upcoming Movies post was not the first time people had been bamboozled by this specific poster, which been bouncing around since at least 2017, when a Philippines-based radio station posted it in a tweet suggesting that it (along with a number of other fake posters) had emerged on Facebook:

The same poster shows up here and there in tweets and Reddit posts; it had another round of recirculation in January, when “Upcoming Movies” posted it. Interestingly, it seems like the poster’s obvious falseness is actually what’s kept it in constant circulation for the last half decade: Many of the reverse image-search results for the poster are Reddit forums and tweets making fun of the poorly aligned title, which seems to read “We’re Part 2 the Millers,” and this stubborn, funny amateurishness may have given the poster a circulation power that more professionally designed, less obviously fake poster, might not have had.

But this doesn’t really “solve” our “mystery”: Where did “We’re Part 2 the Millers” come from? Why does it keep getting posted? What on earth is going on? Of the many mysteries posed by the original (and quite troubling) tweet, perhaps the easiest to answer is the question of why hundreds of thousands of people have responded to a post (falsely) advertising the existence of a sequel to the 2013 Jason Sudeikis/Jennifer Aniston comedy We’re the Millers: People really fucking loved We’re the Millers.

I will confess that I, personally, have never seen We’re the Millers, and indeed have not even thought about We’re the Millers, even once, in the 10 years since it was released, and so the enthusiastic reception of a fake poster for its sequel on Facebook seemed confusing to me. But We’re the Millers was the 16th-biggest movie at the U.S. box office in 2013, and as the comments quoting extensively from the movie on the Facebook post suggest, it has sustained an interested, if not absurdly devoted fanbase over the last decade.

In fact, We’re the Millers is probably the precise right amount of beloved and remembered for a Facebook post like the example to exist: Popular enough that a significant number of people are excited about a sequel, but not so popular that a sequel will actually be made, or even written about much by mainstream publications. To this point, we can tell that We’re the Millers is a popular movie because enough people have googled “We’re the Millers sequel” to make worthwhile the creation of search-engine spam blogs designed to come out near the top of search results for “We’re the Millers 2.” I enjoyed this one, on the site “Keeperfacts.com,” which speculates thusly on the plotline for We’re the Millers 2 (spoilers, I guess, for We’re the Millers):

It’s here that the mystery gets less interesting, or maybe stops being a mystery at all, really. If enough people search for something, the eager economy of SEO spammers will strive to answer those searches with whatever barely adequate garbage it can conjure up.4 This same principle applies to the Facebook-page economy in slightly modified form: Rather than trying to meet searches with your "content," you are trying to generate shares, comments, and reactions with it. Even a patently fake poster works much better for this than a few mangled paragraphs of text; indeed, “Upcoming Movies” seems to have a track record of sharing fake posters for engagement:

This, at least, explains why the poster would be published, and why people would receive it so enthusiastically. But there is a remaining mystery, one I can’t solve: Where did the poster come from in the first place? Was it the product of a We’re the Millers superfan, operating in the deranged and productive creative register of the superfan? Was it the tactic of cunning spammer coasting off the improbably continuing popularity of We’re the Millers? The world may never know.

In December a reader named James emailed me:

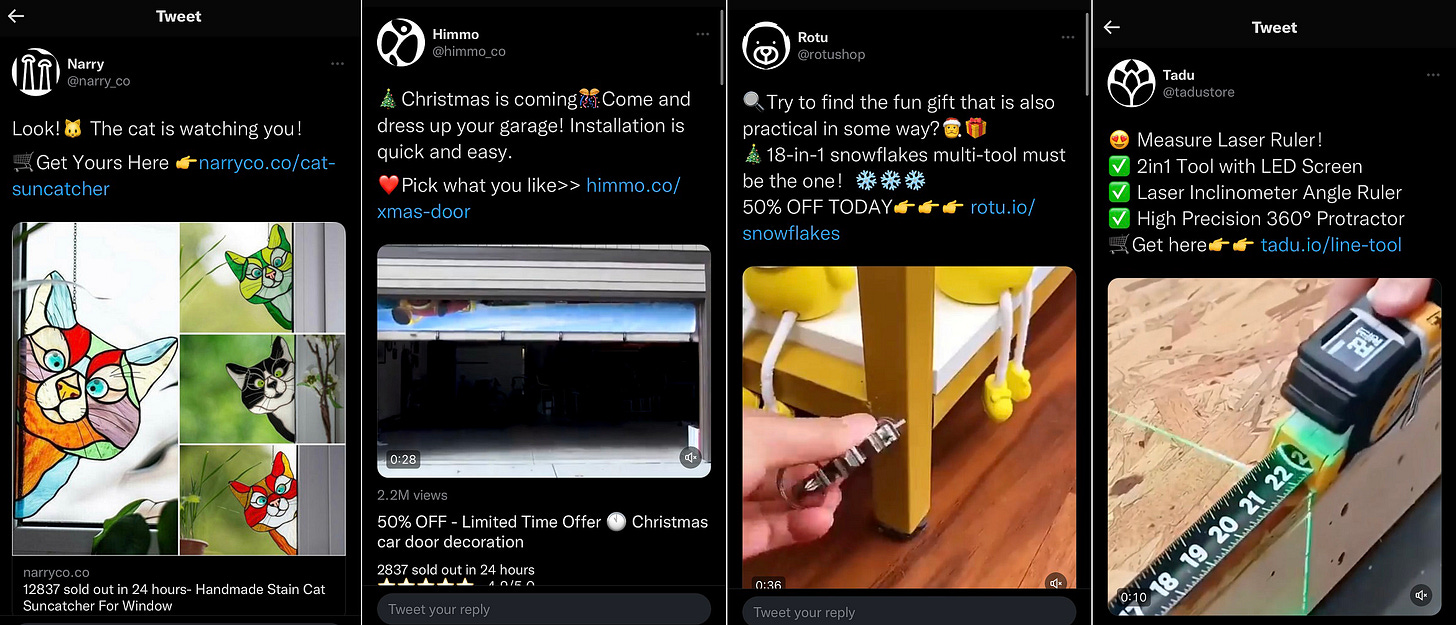

Question for your particular set of skills, along the lines of the wrong-number text scam piece you did a while back. Over the last month or so, at least half of the promoted ads I've seen on Twitter are what feel like dozens of minor variations on the following template: 1) company name/username is a nonsense word, often appended with "co" or "shop" or "store", 2) profile pic is a simple black and white illustration done in a particular style, often of an animal, 3) the product is one of a rotating cast of lifehacky gadgets or household chotchkes, 4) the accompanying short video usually features actors or text in the background that suggests it was produced in China. I'm attaching a few examples I saw in ~5 min of scrolling. I know Mr. Musk has allegedly driven away many of Twitter's advertisers, but it's still suspicious that so much apparent ad buy is now coming from this one approach - what's the deal here? The answer is probably nothing more than "some company in China is using the current lack of moderation at Twitter to create hundreds of accounts to spam ads," but perhaps something more is afoot?

Here are four of the screenshots James sent me:

James was not the only person to notice the proliferation of eerily similar Twitter accounts peddling as-seen-on-TikTok junk gadgets among Twitter’s sponsored posts. (As John Herrman pointed out at the time, Elon Musk had told Twitter employees that he wanted to see more “ads for gizmos” on the site.) I counted nearly two dozen accounts and websites with similar logos, storefronts, wares, and nonsense names: In addition to Narry, Himmo, Rotu, and Tadu, there’s Zodu and Bexe, which like the four James identified also have black-and-white logos and claim to be “committed to providing unique products at tremendous values to our customers”; Zimma and Rommo have identical storefronts to the Zodu/Bexe family of shops but feature rainbow, rather than black-and-white, logos; Dula, Potta (or, according to the logo on the navigation bar at the top, “Putta”), Bezenpy, Bezenfy, and Tozdy, have Zimma/Rommo-style rainbow logos but a different storefront and a promise to “dedicate ourselves to providing the latest blanket, clothes, canvas, ornament, jewels and accessories”; finally, there’s Poxo, Gota, Duno, each of which sports a rainbow logo but claims it “curates 100 amazing fandom-related items and accessories.” All of the sites sell a narrow and largely overlapping range of products, a dollar-store mix of junky gadgets, clothes, household decoration, and ear-wax cleaners.

Is this endless parade of inhuman storefronts peddling chintz … fake? Real? Scam? Legit? Some combination? Why are they all so similar, without being identical? Why do so many of them claim the same nonexistent addresses: An empty stretch of Bakersfield, Ca., between a Basque Restaurant and a Bridal store; a Kurdish grocery store in Manchester, England; and a “head office” apparently located at in Hanoi, Vietnam?

Sadly, despite sifting through strange Google results, fruitlessly messaging the contact emails on these sites, and scouring Google Street View Hanoi, about the only thing I can say with certainty is that they’re almost all using variations the same Wordpress theme, "Woodmart."5 Are are they scams? Well, sort of yes and sort of no: The Better Business Bureau page about “Teppy” suggests that orders are usually filled, but not reliably, and not well. Are they fake? Well, what is a “real” store in the age of Amazon, Alibaba, Shopify, and reliably low shipping costs?

The best I can do here is make a semi-informed conjecture. Vietnam is a popular hub for drop-shipping, an ecommerce strategy where sellers ship items to customers on demand directly from the manufacturer, often located in China.6 One can imagine an Vietnamese entrepreneur with some Wordpress development skills deciding to launch such a business, spread out across several storefronts to expand reach and limit exposure.7 This person, who is not specifically trying to scam people, might use their real address8 on some of these sites, but also make up some American and English addresses to reassure potential Anglophone customers.

At the same time, they might notice that Twitter ad prices are extremely accessible, as Tiffany Hsu covered in a recent New York Times article called “Why Are You Seeing So Many Bad Digital Ads Now?,” the answer to which is essentially “because Twitter is hard up for cash”:

But lately, on several platforms, the opposite seems to be happening for a variety of reasons, including a slowdown in the overall digital ad market. As numerous deep-pocketed marketers have pulled back, and the softer market has led several digital platforms to lower their ad pricing, opportunities have opened up for less exacting advertisers. […]

advertising experts agree that crummy ads — some just irritating, others malicious — appear to be proliferating. They point to a variety of potential causes: internal turmoil at tech companies, weak content moderation and higher-tier advertisers exploring alternatives. In addition, privacy changes by Apple and other tech companies have affected the availability of users’ data and advertisers’ ability to track it to better tailor their ads. […]

Twitter seems to be faring the worst. The company has struggled to retain top-flight advertisers since Mr. Musk took over as owner in October, amid fears of a proliferation of hate speech and misinformation on the platform. Its 10 largest advertisers last year spent 55 percent less during Mr. Musk’s tenure than they did a year earlier, with six of them spending nothing so far in 2023, according to estimates from the research firm Sensor Tower. Twitter has offered buy-one-get-one-free deals, discounts and bonus incentives to lure back advertisers, media buyers said.

What multi-storefront drop-ship mogul could resist this kind of opportunity? And there, at the nexus of cheap shipping logistics and Elon Musk’s hubris, Narry, Rotu, Himmo, and Tadu are born.

Other pillars include Feeling Ambivalent About Technology, Getting Angry at Newspaper, Being Pedantic About Science Fiction, and the Geometric Solid Power Ranking.

This is Sam, the friend who bought the Siemens mousepad from the occult-sciences computer-education nonprofit that was the subject of this newsletter from last October:

Of course, the poster is “real” in the sense that it exists, and was in fact shared on the Upcoming Movies page, but it is not “real” in the sense of “having been created by professionals as part of an intentional marketing campaign to advertise an existing or at least scheduled-for-release movie.”

If you’re lucky, sometimes that garbage is entertainingly strange -- there’s 97-minute YouTube video called, simply, We’re the Millers 2, which consists of Ken Burns-style pans over unsettlingly filtered stills from the first film while a voice synthesizer reads, over a piano soundtrack, an extremely poorly written splog article about the hypothetical sequel, first in Russian, and then in English, Chinese, Hindi, Spanish, Italian, and Japanese.

But sadly these kinds of engagingly uncanny byproducts of a whirling platform economy are less common than they used to be, and often what you get isn’t even charmingly shambolic in a way you can appreciate -- it’s just coherent, dead-eyed, repetitive prose, minimally informative words piling up to reach a particular, Google-approved length.

Whoever is behind the Bezenpy/Bezenfy empire is not the only fly-by-night operator to have installed Woodmart; some lazy shopkeepers didn’t even bother to change out the boilerplate address. If you google around the default Woodmart address (“451 Wall Street, London”) you can find some funny internet artifacts, like this Better Business Bureau complaint about a “Fake Id n DL” business located at (the nonexistent address of) 451 Wall Street, Houston, TX 77072:

An even lazier example can be found at a Ugandan tech store called, improbably, “Woodmart Kampala,” which simply kept the boilerplate logo and name from the Wordpress theme.

For more on dropshipping, I recommend Jenny Odell’s wonderful pamphlet “THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS A FREE WATCH”:

Whatever and wherever it is, the entity in question is using dropshipping, a method whereby a company merely forwards the order from the customer to the supplier / manufacturer, who in turn ships the product directly to the customer. Mentions of “Made in China” stickers, watches coming in clear plastic bags, the MOJUE box, etc. point to the fact that the company or entity is not actually handling (or branding) the watches before they arrive. In fact, Shopify, which is the platform used by Folsom & Co, Soficoastal, etc., has a blog post specifically advising users on dropshipping items from Aliexpress. In the FAQ section of Folsom & Co.’s site, they state: “like many great American companies, we currently ship from our warehouse in Asia.” Such a “warehouse” can only be understood metaphorically, as the process likely involves an entire network of warehouses and distributors, none of which are owned by Folsom & Co.

Alternately, and this is pure, totally uninformed conjecture, you can imagine an entrepreneur whose business is in creating dropshipping businesses for other people -- a middle-man for other middle-men, who sets up near-identical sites with near-identical advertising strategies and either turns them over or passes profits on to the “investors” or “owners.”

An interesting outcome of following this particular rabbit hole has been learning about the structure of Vietnamese street addresses, which often use two numbers to indicate both the building number and the lane or alley number. Because of this, Google Maps mis-locates the address provided on the Bezenpy site, “24/31 Ha Huy Tap, Yen Vien, Gia Lam, Hanoi, VN,” which is located in building 24, lane (ngõ) 31, Ha Huy Tap street.

Do you know who we can contact at Substack to make footnotes into hyperlinks so you don’t have to scroll up and down? I’m ready to sign any and all petitions related to this issue.

Is this a mystery, though? There's an awful lot of clickbait out there, of both the frothy and commercial variety, always has been, just a great deal more these days.