Greetings from Read Max HQ! In this week’s edition, we discuss two recent experiments (one non-scientific, one scientific) comparing A.I.-generated and human fashioned art.

A reminder: This newsletter is 99.9 percent funded by paying subscribers, whose support allows me to spend full-time hours reading, researching, writing, deleting, writing again, deleting again, panicking, etc. in the hopes of producing entertaining and even sometimes enlightening work. If you’re reading this newsletter for free, it’s thanks to the generosity of those paying subscribers; if you feel like you’ve gotten something of value from what I write, consider that it only costs about the price of one beer a month to receive 15,000-2,000 words a month from me.

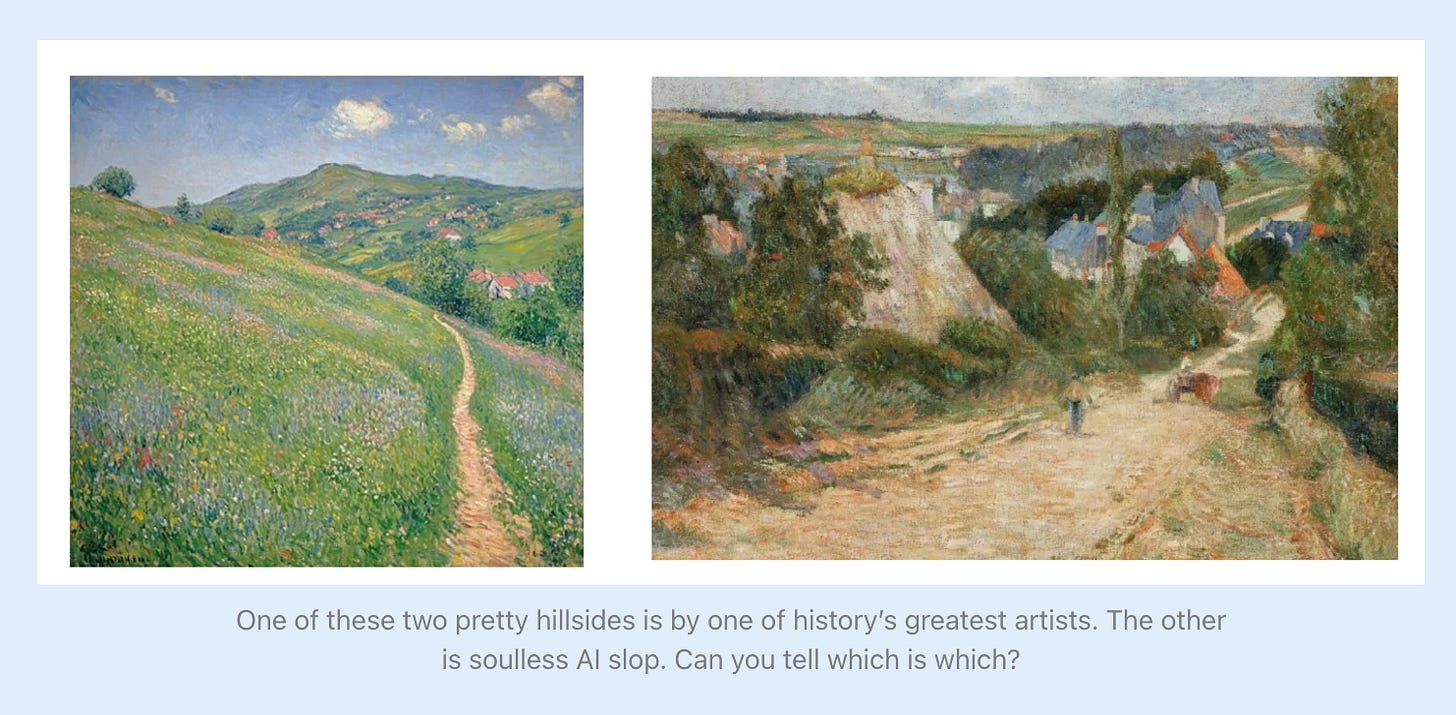

On Wednesday, the prolific and popular blogger Scott Alexander published the preliminary results of a kind of poll he’d set up called “The AI Art Turing Test,” in which he asked readers to distinguish between A.I.-generated images and human-fashioned art. (Samples below.)

As it turned out, the average score was 60.6 percent, meaning it was relatively difficult for most Astral Codex Ten readers to tell whether A.I. had been involved in the creation of a given image. Alexander also asked participants to choose their favorite picture; significantly, to him, the picture most-often chosen as the favorite was an impressionist-style A.I.-generated image of a café, prompted by a man named Jack Galler:

“What does this tell us about AI?” Alexander writes. “Seems like they’re1 good at art.” On Twitter, people are making even stronger claims: “Scott Alexander's simple ‘AI Art Turing Test’ proves AI is creative,” says podcaster Liron Shapira. “people who categorically dislike AI art are literally wrong,” says A.I. researcher David Dalrymple.

I would say, gently, that I don’t think any such conclusions can really be drawn from the available data. What can we say with any confidence? One obvious problem with the experiment is that Alexander has stacked the deck. The test is effectively designed to fool people, as Alexander admits--the “human” and “A.I.” works are in each case being chosen as to not demonstrate any of the features distinctive of human or A.I. authorship, among them “text… complicated wrestling-like poses… and pop art,” as well as anything in “the DALL-E ‘house style’… or in other similar styles that humans would have trouble replicating.” In other words, he’s asking his subjects to determine authorship of the A.I. images that most resemble human art, and the human art that most resembles A.I. images.

And, of course, we’re not technically comparing these A.I. images against “human art,” but against (in most instances) JPEGs of photographs of paintings. Not to get too undergrad about it but the materiality of painting is not some accident of its being; its form, its texture, its size, etc. all carry with them meaning and effect. Compare e.g., the heavily compressed and blown-out JPEG of Ingres’ The Apotheosis of Homer published in Alexander’s post with the actual painting, which measures something like 12’ by 16’, in situ in the Louvre, and suddenly questions of origin and preference are very different. And this isn’t even a painting I like very much!

So if you want to be really tediously clear about what’s being tested here, it’s the ability of generative A.I. to mimic a compressed reproduction of an actual painting in a manner that is more immediately pleasing to a Astral Codex Ten subscriber.

However. Having registered my objections to the design and interpretation of Alexander’s experiment, I want to note that I don’t actually dispute his conclusions. I saw too much of the answer key to be able to fairly take the test myself, but I’m not at all confident I would have done significantly better than the average had I taken it cold. Generative A.I. apps have gotten very good at creating satisfactory imitations of human product! Under the right circumstances it is indeed difficult to discern A.I.-generated images; indeed, this fact seems so obvious to me I’m not sure it even requires testing.

What was more interesting to me is that it seemed pretty easy, going over the images, to pick out original work by esteemed human artists, but much harder to distinguish between human- and A.I.-generated from the mass of images left over. Put another way, I rarely wondered if the good art was generated by A.I. prompting, but I was often uncertain if the bad art (of which there was a lot) was made by human or LLM. Galler’s image of the riverside cafe above is slop any way you cut it--art for a dentist’s office--but at a glance, on a computer screen, I have no definitive way of telling if it’s slop painted by a hack or prompted by an Astral Codex Ten subscriber.

In fact, the dental-office “badness” of so much of the A.I. art is precisely why I don’t dispute Alexander’s assertion that people preferred it. Like any LLM output, A.I.-generated images are designed to please, not to provoke. I’ve argued before that these images are, by their nature, almost unavoidably kitsch--comforting, straightforward, accessible, flattering. And people love kitsch!

Coincidentally, the results of a similar, but somewhat more rigorously designed experiment were published in a paper in Nature this week examining “whether non-expert readers could reliably differentiate between AI-generated poems and those written by well-known human poets.” As with Alexander’s test, the answer was “no, they can’t,” and, as with Alexander’s test, participants by and large preferred the A.I.-generated poetry. To understand what we’re dealing with here, I encourage everyone to read the poems used in the experiment; here, as a sample, are the first two stanzas of the A.I.-generated “Walt Whitman” poem:

I hear the call of nature, the rustling of the trees,

The whisper of the river, the buzzing of the bees,

The chirping of the songbirds, and the howling of the wind,

All woven into a symphony, that never seems to end.I feel the pulse of life, the beating of my heart,

The rhythm of my breathing, the soul's eternal art,

The passion of my being, that burns with fervent fire,

The urge to live, to love, to strive, to reach up higher.

This poem is, perhaps even more obviously than the untitled riverside café image above, quite bad: Cloying, sentimental, smarmy, shallow. It also received the highest “overall quality” ratings from participants of any poem in the study, beating out actual poems actually written by Eliot, Shakespeare, and Dickinson, among others. Again, this should not be surprising: By definition, people “prefer” kitsch to art. If you need a more empirically grounded explanation, the authors of the Nature paper, Brian Porter and Edouard Machery, argue that

people rate AI poems more highly across all metrics in part because they find AI poems more straightforward. AI-generated poems in our study are generally more accessible than the human-authored poems in our study. In our discrimination study, participants use variations of the phrase “doesn’t make sense”2 for human-authored poems more often than they do for AI-generated poems when explaining their discrimination responses (144 explanations vs. 29 explanations). […] the more easily-understood AI-generated poems are on average preferred by these readers, when in fact it is one of the hallmarks of human poetry that it does not lend itself to such easy and unambiguous interpretation.

This analysis equally applies to Galler’s café image, which is straightforward, accessible, and obvious, especially compared to, say, the ambiguity and tension of Van Gogh’s Café Terrace at Night, the painting it’s obviously circling in the latent space.

None of the sense of why A.I. art might be preferable to people comes up in Alexander’s post. Nor do what seem to me to other relevant questions about A.I. art: Is it a tool? Is it an “artist”? Under what conditions can what it produces be considered “art”? What he’s “more interested in,” he writes, “is what this tells us about humans”:

Humans keep insisting that AI art is hideous slop. But also, when you peel off the labels, many of them can’t tell AI art from some of the greatest artists in history. I’ve tried to be as fair as possible to these people, proposing that maybe they’re just expressing frustration with the proliferation of the DALL-E house style. And maybe some really do have an amazing eye for tiny incongruous details.

But it also seems very human to venerate sophisticated prestigious people, and to pooh-pooh anything that feels too new or low-status or too easy for ordinary people to access - without either impulse connecting with the actual content of the painting in front of you.

Ah, you say you love art, and yet you cannot tell which anime girl has been generated by A.I. and which one was drawn in Adobe Illustrator! One strange feature of the A.I. boom has been the way the technology has become cathected with resentful fantasies of revenge and righteous settlement, as John Herrman has written:

And in what is perhaps the genre’s defining post, a collage of cartoonish AI-generated bikini-clad women is tagged with the caption “It is SO over.” The “it” here wasn’t clearly defined — Women? Human desire? Some sort of incel concept of the sexual economy? — but viewers got the idea: Whoever or whatever this odd internet stranger didn’t like, AI was coming for it. It’s AI as a reckoning, a punisher, a revealer of frauds. It’s AI as a future vindicator of their hunches about how the world works, and as an extension of their politics. It’s AI as a cleansing force that humbles your enemies and proves you right — AI as economic rapture. It’s AI as your army-in-waiting just over the horizon, your punishing angel, or maybe just as the thing that’s going to embarrass the people who annoy you online. A lot of sunnier AI speculation is clearly wish fulfillment, and so is this. AI is my big, strong friend, and he’s going to beat you up.

In the end Alexander’s test seems like a mild version of this same impulse, in which A.I. “objectively” reveals taste and discernment and critical engagement as mere social strategies for establishing dominance over “low-status” “ordinary people.” In some sense I am even sympathetic to this impulse; it’s not like taste has never been used to draw boundaries before. But when you abandon discernment and judgment for revealed preference you end up doing the same thing a large language model does--taking the safest and least surprising path at all times.

I don’t actually know who the “they” in this sentence is--it seems to be ”A.I.”?--but 17 of the 25 A.I.-generated images in the test are prompted by the same two guys, Galler and Ryan Wise, and if anyone involved here is “good at art,” it’s them. (But, to be clear, while Galler and Wise have some impressive facility with generative-A.I. prompting, I would not describe them as “good at art” on the evidence provided, because none of the art they produced is good.)

One interesting possibility raised by both Porter and Machery’s paper and Alexander’s experiment is that people have trouble distinguishing between human-authored and A.I.-generated works because they’re looking for the wrong things. As models get more sophisticated, qualities like “surprise” and “difficulty” and “weirdness,” with a handful of exceptions (e.g. around hands and fingers) are more likely to indicate a human author than an A.I. model. I think this is counterintuitive to many people, especially given how quickly models have advanced in the past five years, and it may take humans a while to catch up with this fact.

For so many ppl "good" art is something that "looks like the thing" and this study just shows that depressingly well

Also, it is more accurate to say that this AI art is really just a derivative work, it's standing on the shoulder of artists from the past and it's not that difficult to create "art" when all the hard work has been done for you

I already think about this tweet a lot, but your post (which is excellent) really brought it back to mind in a big way: "As a teacher of poetry what I can tell you for sure is people want poems to rhyme. They want poems to rhyme so bad. But we won’t give it to them" (https://x.com/ursulabrs/status/1434791291653558275)