Never send to know for whom the brain worms; it worms for thee

Toward a theory of, and treatment for, brain worms

You’re reading Read Max, a newsletter about the future. This edition of Read Max is free for all readers. If you like this one, even though it is admittedly pretty annoying/alienating, please consider subscribing.

Paid subscribers get two newsletters a week and access to Read Max archives, as well as my eternal if rarely directly addressed gratitude. This week’s links and recommendations roundup post will appear on Sunday, probably. Sorry for the lateness.

"Brain worms" is a common insult-diagnosis, thrown around Twitter by people across the political compass at enemies and putative allies alike. In real life, "brain worms" usually refers to the pork tapeworm, a parasite that can enter the nervous system and become "stuck in ventricles, or fluid-filled cavities, in the brain, sprouting grapelike extensions" that present as cysts dotting the brain in afflicted patients, though increasingly people use it in reference to the infamous Toxoplasma gondii parasite, which is spread most often in cats and is reputed to induce certain behavioral changes in its hosts (in addition to forming brain cysts), as Joe Rogan and Alex Jones explain in the following video:

If you don't want to sit and watch Rogan and Jones discuss science for two minutes, I can also recommend this video, which requires you to open your third eye:

In the world of online discourse, "brain worms" is used to refer a similar malady, only instead of the pork tapeworm or T. gondii, the parasite is "the internet," or "social media," or "the culture wars." To this extent, "brain worms" is generally coextensive to terms like "brain melt," "brain poisoning," and "extremely online."

But what is "brain worms"? Where does it come from? How does it spread? Are they curable?

Defining online brain worms

If you search "brain worms" on Twitter, you'll see that it's generally applied to political opponents who are expressing beliefs that the diagnostician believes are unsound. But to simply regard "brain worms" as a synonym for "nuts," even if that's how it's often used, loses some of the useful subtlety and poetry of the idea.

It is, you have to admit, a nicely evocative bit of imagery: On one level it suggests a sort of epistemological, or phenomenological, or ideological version of an earworm: an interpretive framework so catchy and irresistible it settles somewhere deep in your subconscious, such that you find yourself humming it under your breath when you read the news. On another level it suggests that your brain is riddled with holes eaten by ravenous, burrowing endoparasites, or maybe that your brain has been wholesale replaced by a pile of wriggling worms, which is very gross. Perhaps, even, the worms are now controlling you and your actions, in the manner of the fungal ant parasite Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, or the alien brain Krang.

"Brain worms," then, carries with it implications of unthinking obsession, cognitive decay, and a fundamental loss of control. You are at the mercy of your brain worms, which circulate in your mind, slowly consuming it until nothing is left but the worms.

Like any scientifically derived medical diagnosis, "brain worms" is a politically and morally value-neutral malady. Anyone can become brain-wormed, for good and for bad. (It is possible to be brain-wormed by things that are completely true and correct!) What matters is not the specific source of the brain worms, or the content of the worms, but how the worms make you act.

Thus, a succinct definition of online brain worms might be something like "a condition where one's thought processes have been rerouted through social media." To have brain worms is to have your interests, your sense of humor, your politics, your personality, and, maybe most importantly, the reference points by which you set those things shifted to orbit a new center of gravity: Your feed.

The evolution of brain worms

Patricia Lockwood's London Review of Books essay "The Communal Mind" (on which her wonderful novel No One Is Talking About This draws) is the definitive statement of the original brain-worms community, a document of a consciousness remapped:

As she began to type, ‘Enormous fatberg made of grease, wet wipes and condoms is terrorising London’s sewers,’ her hands began to waver in their outlines and she had to rock the crown of her head against the cool wall, back and forth, back and forth. What, in place of these sentences, marched in the brains of previous generations? Folk rhymes about planting turnips, she guessed. [...]

The word toxic had been anointed, and now could not go back to being a regular word. It was like a person becoming famous. They would never have a normal lunch again, would never eat a Cobb salad outdoors without tasting the full awareness of what they were. Toxic. Labour. Discourse. Normalise. [...]

The mind we were in was obsessive, perseverant. It swam with superstition and half-remembered facts, pertaining to how many spiders we ate a year and the rate at which dentists killed themselves. One hemisphere had never been to college, the other hemisphere had attended one of those institutions that is only ever referred to as a bubble, though not beautiful. At times it disintegrated into lists of diseases. But worth remembering: the mind had been, in its childhood, a place of play.

Lockwood's essay keys in on an important shift in how brain worms present in their victims. Early brain worms, nurtured on an internet most often encountered as a "place of play," emerged as intrusive phrases and images ("DON'T EMAIL MY WIFE," etc.) dislocated from any kind of productive context — early side effects of exposure to toxic levels of information. For many years, to be "extremely online" simply meant that you had an annoying sense of humor cultivated on message boards among the socially maladjusted.

To be "extremely online" still means you have a fundamentally internet-based set of references. But in 2022 those references map out not simply a epic, random, or “irony-poisoned” senses of humor, but entire worldviews. Referents are not detached from context so much as they constitute their own, independent, self-reproducing context: "DON'T EMAIL MY WIFE," "binch," "absolute unit," "enormous fatberg made of grease" give way to "critical race theory," "dezinformatsiya," "Aimee Therese," "toxic masculinity," "the PMC," the 1619 project. (These words and phrases are examples of where cysts might appear in the brains of people with Twitter-specific brain worms; people with YouTube-type brain worms likely have different trigger words.) Your political and cultural world becomes defined by the people and figures you encounter on your platform of choice, your ideas and opinions shaped by how they engage (or don't engage) with the points of reference.

Brain worms screening

I am mad online…

[ ] a. never

[ ] b. rarely

[ ] c. sometimes

[ ] d. always

I experience joy on the internet…

[ ] a. always

[ ] b. sometimes

[ ] c. rarely

[ ] d. never

I can articulate intelligible opinions about politics and culture to people who have never been online…

[ ] a. always

[ ] b. sometimes

[ ] c. rarely

[ ] d. never

I describe, in detail, to loved ones, disputes between people I've never met…

[ ] a. never

[ ] b. rarely

[ ] c. sometimes

[ ] d. always

I diagnose others with brain worms…

[ ] a. never

[ ] b. rarely

[ ] c. sometimes

[ ] d. always

In the "Jesse, what the fuck are you talking about" meme, I identify most often with…

[ ] a. I don't know this meme

[ ] b. an onlooker to the conversation

[ ] c. Walt

[ ] d. Jesse

If you answered "d." or "c." to more than three questions, see a specialist.

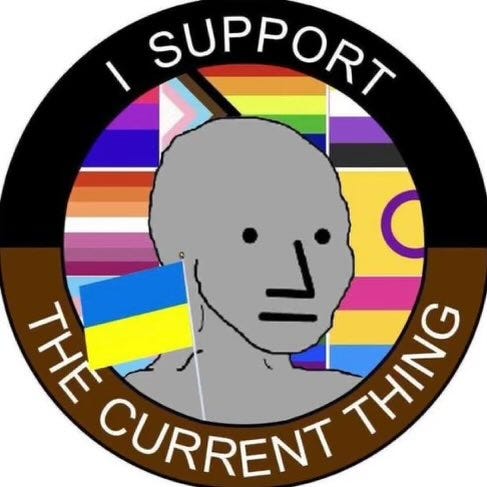

Example of a guy with brain worms

Brain worms: a biological model and treatment strategy

Read Max's working theory about the medical cause of brain worms is that consuming too much content makes your brain soft, pliable, weak, and highly susceptible to brain worms, which feed on information and neurological connection.

While common folk treatments for brain worms such as "logging off" and "touching grass" can help arrest the development of brain worms, and can allow brain worms victims to live long and happy lives, such treatments are rarely able to eliminate the brain worms entirely. Once content has been consumed, it cannot be unconsumed.

Therefore, a strong, well-protected brain consumes very little content, and it undertakes caution and restraint with what content it does consume. Read Max recommends a three-pronged treatment strategy to help limit brain worms:

Information restriction: Rigorously limit the amount of content you consume. Do not, under any circumstances, read or watch "the news," subscribe to any newsletter besides Read Max, or attempt to follow “the discourse.” Mute, block, or unfollow anyone who does.

Refusal to interpret: As often as possible, decline to publicly engage with or interpret events. Repeat to yourself: Sometimes things happen that do not require my attention or input. Practice saying "huh" or "that's crazy" in a noncommittal way.

Tactical stupidity: In many situations, it is better to embrace ignorance. The motto of the healthy brain is: I don’t know what this is and I shan’t be finding out.

Are brain worms contagious?

Brain worms are highly contagious. While it is obviously possible to catch the same brain worms as someone else by reading their newsletter, watching their YouTube videos, or following their tweets, it's also possible to catch so-called "reverse brain worms," where you become so obsessively mad about a worm-infected person or personality that you develop your own case of brain worms.

Arguably brain worms are not a medical condition so much as a kind of cosmic curse: a disease which you can catch simply by having knowledge of it. If you have made it to the end of this newsletter, recognizing every reference, nodding and smiling smugly to yourself at the thought of all the people you can think of who are infected with brain worms, you yourself almost certainly are infected, possibly with a terminal case.

Unfortunately, because there is no cure for brain worms, and even advanced treatment strategies can only mitigate the problem at best, experts estimate that half the country will be infected by brain worms by 2027.

Now I'm worm-pilled.

More seriously, I think there needs to be some investigation into the fine line between being "-pilled" and having brain worms. There's a clear path from one to the other, but they seem to be separate afflictions. For instance one could be "Tooze-pilled" (fantastic call on that BTW) by subscribing to his substack, devouring his books and following him on Twitter without getting brainworms. If Ukraine comes up in conversation with coworkers and you just lol and start yammering about heat pumps and Russian demands for the purchase of gas in rubles, or start shitposting about a Columbia professor, you probably have brain worms.