Lessons from the Silicon Valley Bank bailout

V.C. group chats are a threat to the global economy

Last Friday, the FDIC announced that it was taking control of Silicon Valley Bank, stopping an in-process bank run but starting one of the funniest collective meltdowns in recent memory, as venture capitalists and other tech-industry luminaries took to Twitter to pose philosophical riddles like “actually, SVB bailed out the U.S. government” and “what if we were farmers instead of guys who give money to app developers?”

Happily for the stability of the economy (and those of us who rely to an uncomfortably large degree on the largess of tech-industry workers), but sadly for collective schadenfreude and crisis rubbernecking, on Sunday afternoon the FDIC, the Federal Reserve, and the Treasury Department announced in a joint statement that all depositors in Silicon Valley Bank--not just those under the FDIC deposit insurance limit of $250,000--would be fully protected, and have access to their money as of Monday morning. Additionally, funds would be made available to any banks that were facing similar difficulties.

This is obviously not the end of the entire crisis: There will be more banks to worry about, more regulations to water down, more tech-investor tweets to rub your temples in response to. But it is a reasonable de-escalation, and a relatively good moment to take stock of the lessons we have learned from the events of the last few days.

All bank deposits everywhere are effectively guaranteed by the federal government

Once the FDIC put Silicon Valley Bank into receivership on Friday, the biggest question was what would happen to the depositors’ money. The FDIC insures deposits up to a limit of $250,000, but many SVB clients had significantly more than that in their accounts. Roblox had $150 million just… sitting in cash in the bank. Roku--Roku!--had a shocking $487 million.1

Sunday’s announcement confirmed that all depositors would gain access to their money, and quickly, from the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund (not immediately, as the FDIC might have preferred, from selling SVB to another, larger bank). Yes, even the uninsured depositors, whose recovery would be funded “by a special assessment on banks.”

While certain V.C.s seem to be confident that it was their tweets that pushed the FDIC to this resolution, this was not at all an unexpected outcome. In practice, since the IndyMac failure of 2008, the FDIC has done everything it can to make even uninsured depositors whole. And now, in the wake of the SVB failure, the Treasury’s messaging is essentially saying-not-saying that all deposits, even beyond $250,000, are backed by the U.S. government:

Now, I would hazard to guess that “if you have more than $250,000 in the bank, the government is insuring your entire deposit,” is probably not a practical lesson for most Read Max subscribers, due to most of you not having more than $250,000 anywhere, let alone in a bank. (If you do have more than $250,000 liquid, may I recommend upgrading to the newly renamed “Silicon Valley Bank Tier” of Read Max subscriptions.)

But the lesson is still important in thinking about a long-term political response to the bailout of these uninsured depositors and the ecosystem in which they swim. (Because, make no mistake, this is a bailout.)

While “no losses associated with the resolution of Silicon Valley Bank will be borne by the taxpayer” might be true in a sort of abstract philosophical sense, as Steve Randy Waldman points out, actual humans who pay taxes will bear losses associated with the resolution of SVB in the form of increased fees and rate changes and the banks now on the hook for SVB. And yet while bank losses are socialized, bank profits are not. Matthew C. Klein puts it a bit more bluntly:

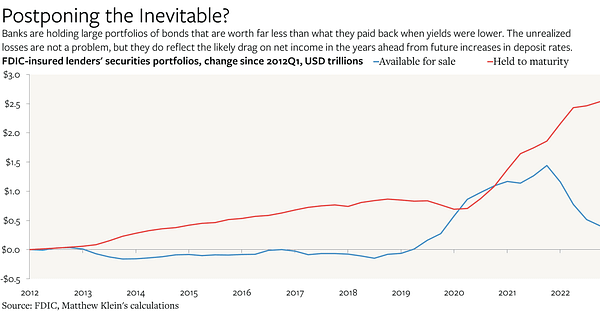

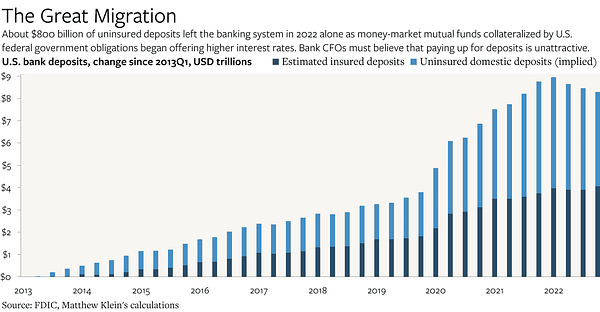

Banks are speculative investment funds grafted on top of critical infrastructure. This structure is designed to extract subsidies from the rest of society by threatening civilians with crises if the banks’ bets are ever allowed to fail. The U.S. government’s response to the collapses of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank—effectively removing the $250,000 cap on deposit insurance while letting lenders borrow relatively cheaply against fictitious asset values—is a reminder that those threats usually work.

But there is a better way. Instead of expanding subsidies to private businesses, the public sector should embrace its role as a financial intermediary. Money and the payments system are public goods. Banks could focus on (what should be) their core competency: identifying creditworthy borrowers and making profitable loans.

I think this is the most important lesson we can take away from the SVB collapse: If all bank deposits are backed up by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, banks in their capacity as depositories and payment processors are essentially public institutions. And if that’s the case, well, why is all my government-insured money funding privately held and profit-generating institutions? Why can’t I just open a free checking and savings account at the Post Office?

Many people really fucking hate Silicon Valley, but most people don’t really care

Many V.C.s this weekend were spouting panicked nonsense about the threat their friends’ bank represented to the global economy. The ones who weren’t doing that were tweeting morosely and aggrievedly about how many people hate them, e.g.:

I found myself particularly, luridly fascinated by the emergent thought experiment “what if we were farmers instead of guys who give money to Stanford undergraduates to make apps, would you hate us then?” which presumably originated on some horrible group chat and quickly spread to the greatest minds of tech:

It seems very, very obvious to me why farmers are more sympathetic than tech investors2, i.e., it is really clear what farming is for (grow food), and much less clear what tech-focused venture investing is for (make app?? insert rent-collecting platform layer into every aspect of my daily life???).3 Frankly, I feel like if this is not obvious to you, perhaps you should step away from Twitter for a while.

But I think it would be wrong for members of the V.C. class to watch the Twitter response to their favorite bank’s failure and take away “everybody hates us.” Everybody on Twitter hates you, because most of the people who are on Twitter who are not V.C.s work in the industries that have been weakened, worsened, and turned completely inside out by venture-funded technology. But the fact is that most normal people don’t really care very much. There was, what, one joke about SVB at the Oscars, and not even a big one? Most people in my social orbit (and frankly most of my subscribers, based on email views!) are simply not following SVB or the “venture capital community,” especially compared to, e.g., Elon Musk buying Twitter, or even to the FTX meltdown.

This should be comforting! There is not actually particularly widespread demand for, you know, à la lanterne. (Yet.) On the other hand, it may also suggest that you, “the V.C. community,” are not really as important as you might believe. Something to mull on, I suppose.

The “All In” podcast must be shut down for its own good

“All In” is a podcast about tech and politics hosted by investors Chamath Palihapitiya, Jason Calacanis, David Sacks, and David Friedberg. It is not the most worst podcast to have ever existed, but in the particular context of the technology industry it is almost certainly the most annoying podcast, hosted by the most annoying people. For the dignity and decency of its own hosts, it must be shut down.

Shut up!!

SHUT UP!!!!!!4

Venture-capitalist group chats are a threat to the world economy

It seems clear at this point that, while SVB made some bad investments relative to interest rates, it likely would have survived just fine had its depositors allowed it to raise capital and extricate itself from its bad position. Here’s how Matt Levine describes it:

SVB is, I think, an unusually clear case of a bank that

was almost certainly insolvent, on a mark-to-market basis: By Friday, if not earlier, its assets, at their current market value, were probably worth less than its liabilities; and

could probably have muddled through and been profitable if people had just kept their money in the bank: Its maturities were laddered, its deposit rates weren’t going up that much, it did have a positive net interest margin even this quarter, it did have various ways to make money, and if people had just kept their money in, the bonds would have matured and been replaced by higher-earning bonds and SVB would have been fine.

And Adam Tooze:

The crucial point is that an ecosystem of depositors was saved. And SVB’s depositors were in no regular sense, depositors. They are badly run and ill-advised businesses that for obscure reasons parked huge cash balances in a highly vulnerable bank. As Matt Klein remarks in his brilliant post at Overshoot the real problem at SVB was that its depositor was base was so “low quality” i.e. extremely prone to run with influence exerted by a small group of VC advisors. This was not so much classic large-scale bank in which mass psychology played its part on a grand scale, as a bitchy high-school playground in which the cool thing to do was to bank with SVB until it no longer was. As Klein puts it: “this was more a case of a “bank-run by idiots” rather than a “bank run by idiots”.”

You may also have encountered this insane tweet, which helps actualize (if not explain) the completely disconnected V.C. thought process:

We’re all pretty familiar at this point with Twitter Derangement Syndrome, through which people can become convinced that Twitter is a 1:1 map of the world, and take positions and form opinions accordingly. But this bank run is a demonstration that Group Chat Derangement Syndrome can be potentially more dangerous: If you’re in a closed group, hearing what is presumably highly sensitive information and advice, without the benefit of an anonymous furry with an accounting degree and a Bloomberg subscription making fun of your ideas in quote-tweets, it’s easy to psych yourself into doing things like making a run on the most important bank in your entire industry.

Luckily, most banks have a more diversified, less pressure-influenced deposit base. But any industry where individuals have instant decision-making power over large sums of money (e.g., finance) is susceptible to Group Chat Derangement Syndrome. For the sake of stability any future securities regulations should probably require traders, bankers, and financial officers overseeing a certain level of funds to disclose their group chats and all participants in tax filings. If we’re going to crash out the economy again because a bunch of idiots who should know better are in a Telegram group called THE BITCOIN BANDITS or something, at the very least we should have some transparency.

Why so many businesses were parking un-insured cash--much of it not even earning interest--at SVB, instead of spreading it across multiple accounts, as is generally common, is still sort of an open question, though in general the answer seems to be that there was a lot of social pressure to bank with SVB. Interestingly, as Matthew Klein points out, the fact that so much of that money was in non interest-bearing cash accounts made it very easy and attractive for depositors to walk away, contributing to the dynamic of the bank run.

Maybe the funniest thing about this thought experiment is that “farming” as an industry is almost certainly more exploitative and monopolistic than technology, and V.C.s could probably learn a lesson about public relations and political lobbying from agribusiness. You don’t see the CEO of Archer Daniels Midland whining on Twitter that people don’t respect his sacrifices!

Admittedly, venture-backed tech companies have improved my life in one obvious way, i.e. by allowing me to participate, on a small scale, in platform rent-collection through the cultivation of a parasocial subscription base. But I don’t think my experience is particularly common.

It’s hard for me to communicate how funny it is that Mahalo founder Jason Calacanis has become a relatively prominent character in the psychodramas of Silicon Valley? Like I’m not even sure how I would describe in a nutshell his general arc, from sweaty dork wannabe to … sweaty dork eminence? It’s almost inspiring.

> If all bank deposits are backed up by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government, banks in their capacity as depositories and payment processors are essentially public institutions.

That's the key insight. Why not cut out the middleman?

Ah, yes, the unprecedented "wealth generation" of VCs. Just perfect. No mention of the Fed juicing the market with ZIRP easy money for over a decade and (like you said) VCs inserting their rent-seeking in every existing social contract built up over the last few centuries. What geniuses! (How do we slap an ad on this? What multi-billion dollar losses can we book with a new app?) Where would we be without them? Maybe not facing the bursting of the biggest super-bubble ever which will, of course, invariably affect the poor and working classes more than anyone else. And they are so goddamned smart they don't even know the most basic risk management.