You’re reading Read Max, a newsletter about the future. This is a Tuesday column, appearing on a Wednesday because it’s December and I had some stuff to finish up. If you like it, please share it with other people: It’s the only way I have to expand my subscriber base and get the word out.

Here's a silly question, occasioned by Lauren Collins's great profile of Alison Roman in The New Yorker this week: Is "cancel culture" "over"? Roman was "canceled" last year; she lost a New York Times position and a TV show when she dismissively criticized two Asian women, Chrissy Teigen and Marie Kondo, in an interview. Reading the profile I found myself wondering about a stupid counterfactual: If Roman had given that interview now, in December 2021, would she have been "canceled"? Would she have been dragged? Lost her Times job and her TV show1?

I ask because, just based on my own nonscientific assessment of the overall vibes, Q4 2021 is very different from Q2 2020, and I am wondering how balances of power and terrains of struggle have shifted over the last 18 months or so.

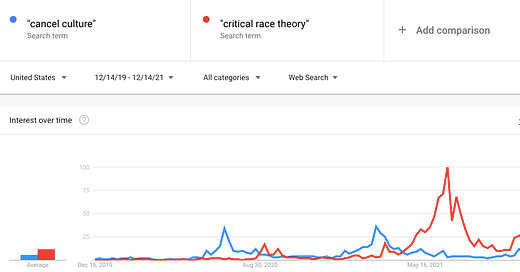

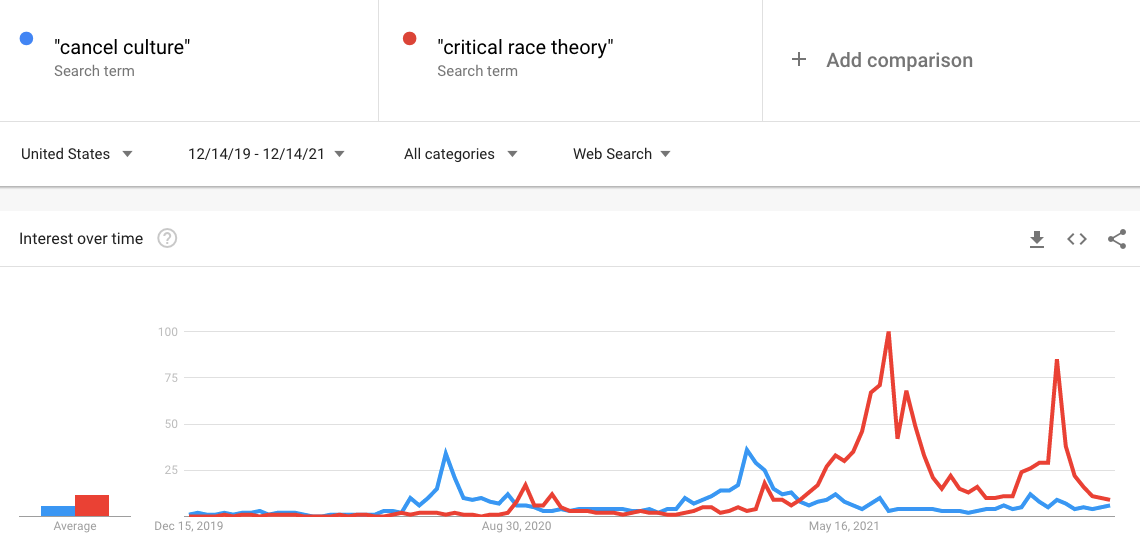

A data point: Sometime this year — Google Trends suggests May — the reactionary centrist-conservative entente moved on from "cancel culture" to "critical race theory." Now even CRT seems stale, as the collective IDW ghoul-brain turns the focus of its paranoid energies toward retail theft, homelessness, and policing. (Look out for "super-meth" in Q1 2022.) "Cancel culture" was always more a figure of the broad right-wing imaginary than it was of the left, and if it no longer animates the Twitter threads and Substack newsletters of our foremost heterodox intellectuals it seems worth asking if it still holds any sway at all.

Of course, if you go on social media, you will still encounter a lot of discourse that people would characterize as "cancel culture" — whether you hold the ridiculously broad definition of "cancel culture" as any and all political criticism, or if you've read the Christopher Lasch Wikipedia entry and come up with some more narrow critical assessment of it as, like, the Calvinist self-discipline of the neoliberal subject on behalf of Woke Capital, or whatever. What seems to have changed — and, again, I'm just going off a nonscientific, albeit expert, assessment of the general vibes here — is not the discourse but the institutional response. When Dave Chappelle released his standup special on Netflix this summer, the external Twitter furor and internal pressure campaign ended not with Netflix cutting ties with Chappelle, but with Netflix firing the trans employee who led the internal campaign. Chappelle was widely condemned on Twitter, sure, but it would be hard to argue Chappelle had been "canceled," even by the silliest, broadest standard. Even the IDW discourse about the special was reduced to anemic complaints about its score on Rotten Tomatoes.

For the purposes of actual thinking, it's probably useful to think of cancel culture not as "college students saying the word 'trauma'" but as a political mechanism. Under the "cancel culture" regime, institutional fear of certain kinds of public anger could be leveraged into professional consequences for people who transgressed social or political norms. "Cancel culture" here describes not (necessarily) a set of values but an arrangement of power, under which institutional prerogative and elite solidarity could be overridden by particular political formations — usually the combination of seemingly mass external anger (on social media and its remora publications) and the organized pressing of demands inside an institution, often by disaffected or frustrated groups of workers and managers. Cancel culture, then, is as much a product of institutions — publications, universities, corporations, movie studios, etc. — as it is of social media. In every instance of "cancellation" I can think of, there were institutional dynamics at play that long predated whatever supposedly cancellable transgression2. The transgression itself, and the attendant social-media "mob," weren't the beginning and end of the story but points of leverage in an ongoing struggle within the institution (or between institutions). The ability to use this leverage is what constitutes "cancel culture."

In this sense, "how people are acting or talking on social media" has always been only part of the equation. The tenor of political condemnation on social media we might associate with "cancel culture" predates, and will outlast, the moral panic about "cancel culture" in society, which suggests that what's at stake isn't an individual social pathology enabled by Twitter but a historical conjuncture, which, if my assessment of the overall vibes is correct, is coming to a close.

This is just a preliminary reading. But it seems hard to imagine the same kind of formations being able to exert the same kind of power over institutions for the same kinds of transgressions as was often possible between, say, 2014 and 2020. The reaction that has emerged in the aftermath of the George Floyd uprising has given political cover to institutions and elites tacking right; we've lived through enough "cancellations" now to see that anger on social media, terrifying though it may be in the moment to institutions and individuals, is fitful and transient, and can be weathered if you use the right playbook. More than anything, I think this is why the IDW circus has moved on from "cancel culture" as an object of obsessions: it no longer holds the same kind of threat, or political power.

(So, would Alison Roman be "canceled" if she gave that interview today? Who knows. A thread running through Collins's piece is that Roman's brash, stubborn self-confidence is both what earned her the "reputation for insensitivity" that allowed her to be “cancelled” in the first place, and also what has made her career as a food personality so successful. More importantly, the profile suggests that it ultimately wouldn't matter much to Roman, now that she's exited the institutional context through which "cancel culture" operates, and relies only on subscriptions to her newsletter and YouTube channel for a living.)

Thank you for reading Read Max, a publication about the future. If you subscribe, you get two posts a week: a column like this, and a list of reading (and other) recommendations. Please consider sharing this post so I can stay off Twitter for my own and others’ safety.

Depending on how you structure the counterfactual, the answer may just be a straightforward "no," because Roman's main antagonists for that particular episode, Teigen and the houseguest/journalist Yashar Ali, have been, if not canceled, reassessed by the ratings agencies of the public unconscious.

Collins’s profile, I think, is a good treatment of “cancellation” that does its best to grapple with the fullness of what ended up being a weirdly complicated episode, even by the standards of “cancellation.” She doesn’t really attempt to litigate the interview quotes themselves, or adjudicate the harm done — which is the usual mistake people who write about “cancelled” figures do. Instead she focuses on the social and professional contexts that might lead to such an episode; you aren’t expected, as the reader, to either condemn or forgive Roman, just to understand how and why someone with her personality, in that profession, at that historical moment, might end up in the position she did. That being said, I agree with this tweet, and it seems to me future historians will have a lot of trouble understanding 2016-2020 on Twitter if they don’t know who Yashar was.

"reassessed by the ratings agencies of the public unconscious" is a perfect way of putting it Max.