Is A.I. generated audio good for anything? (Besides shitposts)

Plus: Marques Brownlee and the decline of gadget blogging

Greetings from Read Max HQ! This week’s newsletter is accompanied, for the second week in a row, by a Read Max-brand Experimental Audio Product, or podcast, that consists of an entertaining (?) if somewhat meandering read of the contents of this newsletter. That podcast can be found (and listened to) here on Substack, Apple Podcasts, or on the podcast platform of your choice. Email subscribers to Read Max should see it show up in their inboxes alongside this one.

In this edition of the newsletter:

We consider A.I.-generated audio “deepfakes”: Are they good for anything? Are they good at anything? What is their likely effect on society?

Why Marques Brownlee, the internet’s last gadget blogger, is being attacked by tech psychos.

A reminder! Read Max is supported entirely by paying subscribers. For the low price of $5/month or $50/year your can help fund the commentary, reporting, shitposting, and, now, finally, amateurish podcasting that defines Read Max. If you find what I’m doing here at all worthwhile, please considering showing your support.

Are A.I.-generated audio deepfakes good for anything?

Recently in the metaphorical pages of this newsletter I asked what generative A.I. apps are “for.” I meant this question mostly rhetorically, as a way of getting at the wild and generally mutually exclusive desires that A.I. enthusiasts project onto this latest generation of A.I. software. But I do sometimes mean “what is this for?” quite literally, such as in the case of A.I. apps designed to reproduce real human voices, the most famous of which is made by a company called ElevenLabs, at whose website, for a low fee, you can upload audio recordings of anyone’s voice and generate new recordings of that voice saying anything you’d like. Maybe more than any other generative-A.I. tech, voice cloning feels like an impressive parlor trick that is mostly bad for the world; its main practical use, so far, seems to be, basically, different kinds of fraud.

You’ve probably already heard stories about fake-kidnapping scams perpetrated by criminals who clone voices from videos on social media; Charles Bethea recently documented a few for the New Yorker:

One Friday last January, Jennifer DeStefano, who lives in Scottsdale, Arizona, got a call while walking into a dance studio where the younger of her two teen-age daughters, Aubrey, had just wrapped up a rehearsal. The caller I.D. read “unknown,” so DeStefano ignored it at first. Then she reconsidered: Brianna, her older daughter, was on a ski trip up north, and, DeStefano thought, maybe something had happened. She took the call on speaker phone. […] Briana said, “Mom, these bad men have me. Help me, help me, help me.” One of the men took the phone, as Briana sobbed and pleaded in the background. “I have your daughter,” he said. […] DeStefano eventually got ahold of her older daughter. “I have no idea what’s going on, or what you’re talking about,” Briana told her. “I’m with Dad.”

And last week you may have read about the Baltimore-area high-school principal who was briefly suspended from his position after the school’s athletics director allegedly created and circulated a convincing A.I.-generated audio file of racist remarks being made in the principal’s voice:

Darien was charged with disrupting school activities after investigators determined he faked Eiswert’s voice and circulated the audio on social media in January, according to the Baltimore County State’s Attorney’s Office. Darien’s nickname, DJ, was among the names mentioned in the audio clips authorities say he faked. […]

Police say Darien made the recording in retaliation after Eiswert initiated an investigation into improper payments he made to a school athletics coach who was also his roommate.

The funny thing is, while fraud, slander, and reputation destruction may be the main practical uses for voice-cloning software, it’s not even clear that it’s actually all that good for those activities? Not only was the athletics director arrested and charged, but local Baltimore media twigged early on that the audio was likely A.I.-generated. Similarly, both scams Bethea covers ultimately failed, since the targets were able to simply call the supposed kidnapping victims on the phone and confirm that they were not kidnapped. It’s easy enough to read these stories and extrapolate out a future where even more sophisticated and frictionless voice-cloning technology creates an endless parade of unstoppable scams and scandals. But a much more likely, if no less dystopian, future is one in which amateurish and avoidable frauds and scams and campaigns continue forever while we never address the problem collectively at all, and instead individually develop a set of organic defense mechanisms against flood of obvious A.I.-generated audio hoaxes, the way everyone I know now declines to pick up the phone when they receive a call from an unknown number. One can imagine, for example, families deciding on secret authentication phrases to verify each others’ identities, though to be honest even that is probably going too far--based on my reading of hardboiled detective novels, authenticating the identity of supposed kidnapping victims has been a problem that predates artificial intelligence by many decades. The main and inevitable “organic” defense mechanism is simply reduced overall trust in audio recordings.

So what is A.I.-generated audio good for? Bethea’s article attempts to helpfully sketch out some non-malicious uses for A.I. audio generation:

Voice-cloning technology has undoubtedly improved some lives. The Voice Keeper is among a handful of companies that are now “banking” the voices of those suffering from voice-depriving diseases like A.L.S., Parkinson’s, and throat cancer, so that, later, they can continue speaking with their own voice through text-to-speech software. A South Korean company recently launched what it describes as the first “AI memorial service,” which allows people to “live in the cloud” after their deaths and “speak” to future generations. The company suggests that this can “alleviate the pain of the death of your loved ones.” The technology has other legal, if less altruistic, applications. Celebrities can use voice-cloning programs to “loan” their voices to record advertisements and other content: the College Football Hall of Famer Keith Byars, for example, recently let a chicken chain in Ohio use a clone of his voice to take orders. The film industry has also benefitted. Actors in films can now “speak” other languages—English, say, when a foreign movie is released in the U.S. “That means no more subtitles, and no more dubbing,” Farid said. “Everybody can speak whatever language you want.” Multiple publications, including The New Yorker, use ElevenLabs to offer audio narrations of stories. Last year, New York’s mayor, Eric Adams, sent out A.I.-enabled robocalls in Mandarin and Yiddish—languages he does not speak.

Of these only the first is remotely convincing as a societally beneficial use; the rest seem at best misguided and at worst actively hostile. I’m not convinced that voiceover labor is a particular drag on overall economic productivity; even if it were, tech that allows celebrities to start treating their voices as rentier assets would seem to cancel out any productivity benefits.

There is, of course, one other prominent and clearly societally beneficial use of this tech: shitposting. More even than their image- or text-generating cousins, A.I. audio-generating apps are extremely conducive to remarkably stupid and funny jokes. You are likely familiar with the videos in which the A.I.-modeled voices of Donald Trump and Joe Biden talk shit while playing Overwatch, or the videos in which an A.I. model of Dan Castellaneta’s Homer Simpson voice sings ‘90s hits like Underworld’s “Born Slippy”; more recent developments in high-level shitposting have seen a series of renditions in which the A.I.-modeled voice of the late country star Toby Keith sings Maoist anthems:

I suspect that one reason voice cloning has made itself so useful to both scammers and shit-posters is that it’s truly novel and truly democratizing, in a way that text- and image-generation aren’t. ChatGPT and MidJourney, to name two popular examples, are impressive and powerful apps. But “text generation and manipulation” has been a technology available to everyone since the advent of mass literacy--by which I mean, anyone can produce text if they know how to write!--and “image generation and manipulation” was similarly democratized by the advent of Photoshop. “Precise impersonation of real voices,” on the other hand, was basically the domain of talented mimics until last year; it wasn’t something that anyone could do given five dollars, a minute of audio, and an internet connection.

One consequence of the uneven and lagging “democratization” of audio generation is that people are collectively less conditioned to mistrust audio recordings. We’ve been very used to the idea that photos can be manipulated (or wholesale created) simply and cheaply since well before the advent of generative A.I., and I think most people “read” images with a sense of skepticism if not outright suspicion--sometimes too much so. (Text, of course, has been a suspicious medium since the fourth century B.C.E.) I suspect that audio is encountered much less skeptically.

Especially, I should say, audio of non- or barely public figures like local principals or family members. One function of the apocalyptic/messianic imagery favored by tech investors to describe the advances of the latest generation of generative-A.I. apps is that people tend to imagine any socio-political effects as being high-stakes, widely visible, and often global in scope. A recent Nieman article about “how to identify and investigate AI audio deepfakes” describes the “potentially disastrous consequences for at-risk democracies.” But--without wanting to downplay the use of faked audio in political campaigns--I wonder a bit if national elections and global politics--highly visible contexts where extensive journalistic and political resources are generally brought to bear--are really the arenas in which we should be most worried about A.I. generated audio using cloned voices. The world system, debased and deteriorating though it might be, has a lot of experience with misinformation and tampering, after all, and it’s still capable enough to defend its continuing operation against cloned voices, faked audio, and whatever else OpenAI is coming up with.

In fact, the deleterious effects of A.I. seem much more likely to be felt--and indeed, as the stories of attempted fraud and petty revenge suggest, are already being felt--on a much smaller, more local, generally tawdrier scale, despite the planetary claims of tech execs testifying to Congress. New kinds of targeted scams and new types of local gossip rather than mass propaganda campaigns; less “state-sponsored misinformation” and more “provincial-psychopath-looking-to-settle-a-school-athletics-grudge-sponsored misinformation.” And, just as the threat of “state-sponsored misinformation” has led some people to see Russian influence everywhere, the threat of “some guy making deepfakes” allows others in these local contexts to accuse unflattering real video of being deepfaked. What generative A.I. is doing as much as anything else is democratizing psy-ops--now anyone can be their own personal local C.I.A. dirty-tricks office.

In this analogy, I guess, deepfake audio shitposts are abstract expressionism. I’m a longtime proponent and supporter of shitposting, one of the last truly human activities on the internet, and I don’t want to discount the joy these videos give me. But I am not sure that, for me at least, the ability of a pill-addicted, irony-poisoned TikToker to make Toby Keith sing “the sun in my heart is Mao Zedong” outweighs “kidnapping fraud at scale” and “automatic slander generation” on the balance sheet.

The life and death of gadget blogging

Once upon a time, the most profitable, and in some sense the only kind of publishing business on the internet was “the gadget blog.” For all the attention Gawker received from scandalized journalists, the traffic juggernaut at Gawker Media was its sister site Gizmodo, the gadget blog, which founder Nick Denton quite openly conceived as “Wired, but only the page in the front-of-book where they show cool gadgets.” For most of the 2000s, Gizmodo and dozens of rivals were generating (what was at the time) immense traffic writing about phones, cameras, MP3 players, TVs, computers, Apple events, consumer-electronics expos, and so on.

There are many reasons that gadget blogs were dominant in the 2000s--among other things the total audience of people online wildly oversampled nerds, and as non-nerds started consuming news online the gadget-blog audience share decreased in relative if not absolute terms--but maybe the main reason is that back then gadgets were kind of cool and exciting. The flowering of new, useful, affordable consumer technologies in the late 1990s and early 2000s--the geopolitical/economic story of which is likely fascinating but beyond the scope of this newsletter--meant that there was more than enough subject matter to sustain a whole ecosystem of blogs and proto-influencers producing product announcements, product reviews, product photo galleries, product tips and tricks, vaguely humorous “rants” about products, etc.

The launch of the iPhone in 2007 started a decade-long process by which a huge swathe of the product categories--MP3 players, cameras, GPS systems--that sustained gadget blogging were obviated. Even smartphones themselves, once a diverse product category, began to carcinize into largely indistinguishable flat glass rectangles running one of two remarkably similar operating systems. “Silicon Valley,” named for what it once manufactured, was becoming synonymous not with hardware but with software, and gadget blogs seemingly had no choice but to follow along. Gizmodo, Engadget, the Verge all still review prominent products when they come out--but they’re generalist “tech” sites now, writing about the software companies. There are no more gadget bloggers.

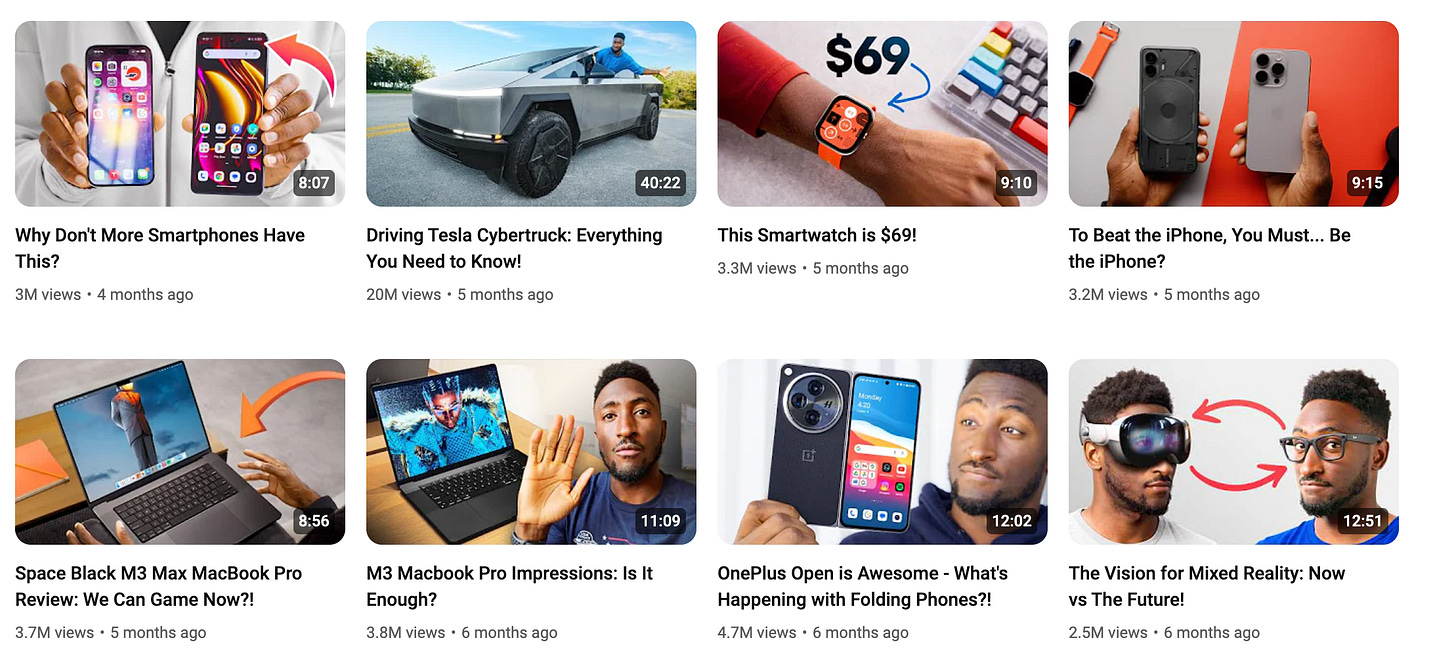

Except for Marques Brownlee, who is, to be fair, not precisely a blogger. Brownlee is a phenomenally popular gadget YouTuber, whose channel is filled with reviews, comparisons, and breakdowns whose subjects--and affably nerdy tone--are as close as you get to an old-fashioned gadget blog on the internet these days.

For the reasons outlined above--the rise of the iPhone and high-margin software businesses as the economic engines of the American tech industry--there have simply not been that many new gadget categories over the last decade or so of Brownlee’s rise. Where gadget blogs of the 2000s were obligated to cover a range of often quite new and janky products, MKBHD (Brownlee’s channel) tends to focus on in-depth, multi-video examinations of flagship products from major hardware companies like Samsung and Apple, plus shorter reviews of the many entrants in competitive categories like smartwatches. And, as most former gadget blogs and other tech media have grown (appropriately) skeptical of the tech industry’s costs and ambitions, Brownlee’s focus on consumer products and status as the heir of gadget blogging--and of the tradition’s overall tech optimism and enthusiasm--has made him extremely popular in Silicon Valley. Until recently.

Three distinctly negative reviews--of the Fisker Ocean E.V. (“This is the Worst Car I’ve Ever Reviewed”), the Humane A.I. pin (“The Worst Product I've Ever Reviewed... For Now”), and the Rabbit R1 personal A.I. device (“Rabbit R1: Barely Reviewable”)--have produced a piercing collective whine from tech investors and executives on Twitter, complaining that Brownlee was being negative, pessimistic, mean, whatever else:

Brownlee has ably defended himself already, not that he should need to defend himself to any sane person. But it also seems worthwhile putting what he’s doing in the broader context of U.S. gadget media and its relationship to the tech industry. It seems unsurprising that two of the three negatively reviewed products were attempts to create a whole new category of gadget based on A.I. Over the past decade, a lot of tech-business whizzes have gotten used to ignoring tech media as “haters” because the software they produce is often a system of traps designed to ensnare users whose attention or subscriptions can be extracted. (That, or it’s enterprise and its success depends on your sales team.) Consumer products that can be exchanged for money are a very different category, held to different standards, and promises to “iterate” are not as enticing. The reminder that hardware products generally need to be designed, not merely thrown up for free on a website in the hopes that profitable uses can be found before the venture capital dries up, is a useful one.

Some folks in the Sandlot baseball league here are using Midjourney to make VERY bad posters for their baseball games. Also LOL at that guy being like "good thing he didn't review Iphone 1". It actually worked and did everything it promised well.

That Homer "Born Slippy video" and its slurry of various random pop culture characters dancing like a Fortnight lobby are going to be stuck in my head forever now