What is this?

Read Max is a newsletter devoted to explaining the Weird Future, and Elon Musk’s purchase of Twitter (and the media meltdown that’s accompanied it) deserve some explaining.

As the story has developed, Read Max’s content and research department has sent out many newsletters, featuring original analysis as well as collecting and recommending smart, informative, or, at the very least, funny writing about Twitter, Elon Musk, the media, Mastodon, and the other aspects of the multi-billion-dollar mid-life crisis.

On this page, we’ve collected all of that reading into something between a syllabus and an explainer -- a starting place for anyone trying to learn more about whatever the fuck is happening with Musk, the Babylon Bee, Kanye West, etc. This page was most recently updated on 11/30/2022. Click below to go straight to the latest information.

This is sort of an experiment, so I’m sharing it as a free post; If you find it useful (or, at least, sort of entertaining), please pass it on to people who you think would appreciate it.

This attempt at explaining Elon Musk’s whole deal to the general public took a lot of work, and was supported entirely by paid subscribers. If you want to see more free and public explainers like this, consider supporting us with a paid subscription to Read Max.

What has been happening with Twitter?

Tesla CEO and eager meme-sharer Elon Musk purchased the company and took it private for $44 billion. After buying it, he fired half of the staff and then lost another three-quarters to a Google Form. He reinstated banned and suspended accounts like Donald Trump and Kanye West, and has been posting it through it this whole time.

Probably the best blow-by-blow of Musk’s tenure can be found in Casey Newton and Zoey Schiffer’s reporting on Platformer, which has been quite good, but especially this:

Just after noon, an executive assistant asked engineers to begin preparing code to show to Musk.

“Please print out 50 pages of code you’ve done in the last 30 days (if you haven’t submitted code in the past 30 days, then you can go back up to 60 days),” the assistant wrote in a Slack message obtained by Platformer. “Please be ready to show on your computer as well.”

“Recency of code is important but also use a code that shows complexity of our code,” she added.

By mid-afternoon, printouts were seen everywhere at Twitter headquarters, I’m told.

In mid-afternoon, the instruction changed again. A notice went out to employees ordering them to cease printing out their code, for reasons that were not immediately clear.

“UPDATE: Stop printing,” read another bolded notice obtained by Platformer. “Please be ready to show your recent code (within last 30-60 preferably) on your computer. If you have already printed, please shred in the bins on SF-Tenth. Thank you!”

What was Twitter, before this?

If nothing else, Musk’s purchase of Twitter has occasioned some nice writing on its decade-long existence as one of the internet’s stupidest and most powerful spaces. Here’s Ben Tarnoff at the New York Review:

The Jamaican theorist Sylvia Wynter says that we are a storytelling species: homo narrans. We use storytelling to define what it means to be human and which particular humans we are. One can then speak of different “genres” of the human: different kinds of stories that make different kinds of people. What Twitter became, as it evolved from a startup into a fixture of the Internet in the 2010s, was nothing less than a machine for the production of new genres of being human. “A new type of guy just dropped,” the meme goes. Over the years, a bewildering variety of types have been produced. A very partial list would have to include Weird Twitter, Black Twitter, Left Twitter, and Trump Twitter, each with their own elaborate genre conventions and extensive internal differentiation.

Any revolutionary breakthrough curdles with this idea of the ‘right people’ – first of all, those springing up to interpret and police the breakthrough. But as dankly cryptic as Twitter often is, it has never really needed interpretation – it’s where you were discovering all your new pals as they stepped out of the cackling mob. As you found one another, the self-serious gatekeepers and envy-wrecked rich kids – including Musk – were doing the same, unstoppering their inner musing and joining in. And often instantly telling on themselves, and being clattered for it byliteral nobodies who abjure capital letters and are funnier, quicker writers and name-choosers. Most of the worry at internet anonymity – and too much of the chatter about toxicity – comes down to this: the wrong people being free to mock the Important People ... as the endless finger-wagging meltdown demonstrates.

How else might we describe Twitter? I liked Ben Walsh’s newsletter suggesting that it’s like a slightly seedier cousin of the publication service PRNewsWire, which companies use to blast press releases across a number of different news services:

What people who are really on Twitter cannot fully internalize is the fact that everyone else experiences Twitter off of Twitter. They see embedded tweets in a People Magazine story, they see screenshotted tweets somewhere, they read CNN or NYT stories about people talking about tweets. It’s a media twitter cliche to complain about the inelegance of the phrase “took to twitter,” but it really is a useful. Almost everyone who interacts with Twitter does so by hearing about people who took to twitter.

In other words, Twitter is the PRNewswire of the social media age. Not all news is made on Twitter, but a certain kind of news is made almost exclusively on Twitter. If you’re a company announcing a deal, head over to PRNewswire and instantly, your press release is on the Bloomberg terminal and dozens of newswires. PRNewswire is so effective at getting information where it needs to be that it is an SEC approved method of corporate disclosure. If you’re a celebrity and your PR team has fired up a notes app apology for you, it’s time to take to Twitter.

The problem for Elon Musk is that PRNewsWire is worth $2 or $3 billion, not the $44 billion Musk paid for Twitter, and it’s hard to see how a bunch of weird little freaks paying to be verified translates into an extra $40 billion in value for the company.

Why did Elon Musk buy Twitter?

As Rohan Salmond pointed out last week, a (the?) key precipitating event for Elon Musk making an offer on Twitter in the spring was the temporary suspension of The Babylon Bee, a Christian version of The Onion that was popular among conservatives for its humor-signaling and insistent transphobia:

Twitter suspended The Babylon Bee’s account on March 22, after labeling a post about transgender Biden administration official Rachel Levine as hateful content. Not long afterward, billionaire Elon Musk, a fan of the site, got a text from his former wife, Talulah Jane Riley.

“The Babylon Bee got suspension is crazy!” read the text, which was made public earlier this year. “Why has everyone become so puritanical?” Then Riley suggested Musk buy Twitter and either delete it or “make it radically free-speech.”

Well, the Babylon Bee is now back on Twitter, among other previously suspended/banned accounts, and Musk is clearly either deleting Twitter or making it radically free speech, most likely the former, so I guess it’s nice that Musk still takes his exes’ needs seriously.

What was wrong with Twitter?

Among the big winners of the last few weeks has been Jack Dorsey, whose dry, almost avant-garde incompetence as Twitter’s CEO seems to have already been forgotten in the wake of Musk’s much louder and more colorful slapstick mismanagement. This Twitter thread from Dan Luu, a blogger and former Twitter engineer, nicely lays out the way Dorsey (and Parag Agrawal) put Twitter in the position it now finds itself in, and how Musk is somehow actually making the situation worse:

In principle, this makes Twitter a juicy PE target: 1. Buy company 2. Cut costs 3. Profit. But, if you look at how PE firms operate, even specialist PE firms, e.g., a specialist firm that operates in the steel industry, those firms typically do takeovers where you can turn big knobs to cut costs; the things above would be considered very sophisticated and ∴ risky. […] It turns out it's really hard to tell who can actually execute on cost savings. Even insiders mostly get this wrong. Now outsiders are trying to do it. […] Even if you could identify who could execute, the lack of trust in leadership would make it very difficult to hire people with institutional knowledge who could be effectively immediately; same thing that's causing most people to turn down the re-hire offers that've gone around.

Who were the employees of Twitter?

I highly recommend this Dan Luu thread on some of the genuinely interesting and challenging engineering work undertaken at Twitter over the years, which puts to bed the sense emerging from the Musk-fan right that Twitter’s employees were pathetic or incompetent or simply not interested in challenging work. For a good sense of why even Musk-curious Twitter employees decided not to click “yes” on Musk’s Google Forms document, this thread from recently former Twitter engineer Peter Clowes is good:

Nevertheless myself and others were banding together, triaging services, updating on-call, literally saying to my wife on Tuesday “I’ll give it my best shot what do I have to lose?”. Then Wednesday offered a clean exit and 80% of the remaining were gone. 3/75 engineers stayed. If I stayed I would have been on-call constantly with little support for an indeterminate amount of time on several additional complex systems I had no experience in. Maybe for the right vision I could have dug deep and done mind numbing work for awhile. But that’s the thing… There was no vision shared with us. No 5 year plan like at Tesla. Nothing more than what anyone can see on Twitter. It allegedly is coming for those who stayed but the ask was blind faith and required signing away the severance offer before seeing it. Pure loyalty test.

On behalf of my subscribers I am monitoring discourse emerging around the class status of Twitter workers, but as of the time of publication I do not recommend reading about or engaging with this discourse, which is for brains in advanced stages of decay only.

What was the whole deal with verification?

Among Musk’s first acts at Twitter was to announce that “verification” -- the internal process by which Twitter certified certain accounts as authentic and assigned them little blue badges -- was now open to anyone who would pay an $8 fee. This move was baffling to everyone except a small sliver of resentful conservatives and Silicon Valley entrepreneurs who believed that verification was an unfair status symbol given to journalists, whom they hate. Katie Notopoulos wrote the essential history of verification and its discontents:

Twitter wanted to be known as a place for news and wanted to encourage journalists to tweet more (a real wishing-on-a-monkey’s-paw situation, it turned out). They rightly guessed that handing out a verification check mark was enough of an ego stroke to that crowd that they’d happily start tweeting more.

Thus there became a massive middle class of verified users who weren’t at all famous and not in much danger of impersonation, but enjoyed its benefits. Verification often led to more followers, and more followers could in turn lead to professional success. Verification also offered some technical perks: a feature to sort your notifications by verified-only replies and faves and access to performance data about your tweets. It also meant that if you ever had a problem with your account, you could get concierge help instead of going through the normie support channels.

On Intel, John Herrman had a good piece about the philosophy and consequences of a pay-for-verification scheme:

The vast majority of people who are on Twitter don’t derive much or any material value from the platform, which, according to Twitter’s most recent public filings, prices their attention to advertisers at about two dollars a month. The few that do will soon be given a choice to make based on admittedly imperfect information: Is whatever they’re doing there worth it? And will it stay that way? By asking heavily invested users to pay to remain or become verified and to remain or become visible — to maintain their brand, whatever it is — Twitter is treating this group of users almost exactly the way it has treated its other most important customers for years: advertisers.

My own take on this question can be found here:

What is Mastodon?

Mastodon is a “federated” Twitter alternative -- platform software that can be run on multiple servers, each with its own community and moderation rules. One such new server, a journalist-run instance for media folks, has attracted a lot of attention for being extremely wack.

Here’s Rob Horning on his newsletter Internal Exile on the possibility that Twitter-alternative federated social platform Mastodon is not annoying enough to truly replace Twitter in people’s dark little hearts:

The “make addicts pay” model presupposes that Twitter’s addictive substance is at once deliberately calibrated and yet undilutable by the addition of fees and shakeups in the composition of audiences. When Levine half-seriously tries to consider the optimistic case for Twitter under Musk, he imagines that “it’s possible that he will make Twitter more pleasant to use, reducing spam and giving users more control over what they see and how they interact. It’s possible that the result will be a more customizable Twitter experience, where some people will choose a Twitter that is optimized for getting in fights and others will choose a Twitter that is optimized for keeping up with celebrity news or whatever.” That contradicts its masochistic appeal, which rests in enforcing the absence of choice. One doesn’t get to consciously optimize Twitter for the experience they want to have but is instead brought to bear witness to all sorts of encounters and trends they still want to be able to disavow. “The hell site made me commit discourse.”

Is Elon Musk making a phone?

After Thanksgiving, Musk decided to pick a fight with Apple, partly because it had apparently stopped the bulk of its advertising on the site …

… and partly because (again, apparently, according to Musk), threatened to remove Twitter from the iOS App Store:

On the one hand, Musk is correct that the App Store approval process is opaque and arbitrary, and basically gives a bunch of guys somewhere deep in the bowels of Apple an enormous amount of (often poorly deployed) power over the software industry. On the other hand, it is admittedly extremely funny that Elon Musk spent $44 billion without thinking about the fact that his new plaything exists at the whim of Tim Apple.

But where most CEOs are dedicated to maintaining smooth relationships with important clients, suppliers, and business partners, Elon Musk is dedicated to other tasks, such as calling CEOs of companies that stopped advertising on Twitter to yell at them, and saying the very first thing that comes to his mind, such as: “if Apple kicks me off the App Store, I will make an alternative phone”:

I don’t think, at this point, we need to go into the complex logistical, mechanical, and cultural reasons why “spinning up an alternative smartphone whose main appeal is its ability to download the Twitter app, on which you can engage with Elon Musk and various white supremacists.” Nevertheless, the imminent existence of the phone has become an article of faith among Twitter’s most devoted Musk supporters:

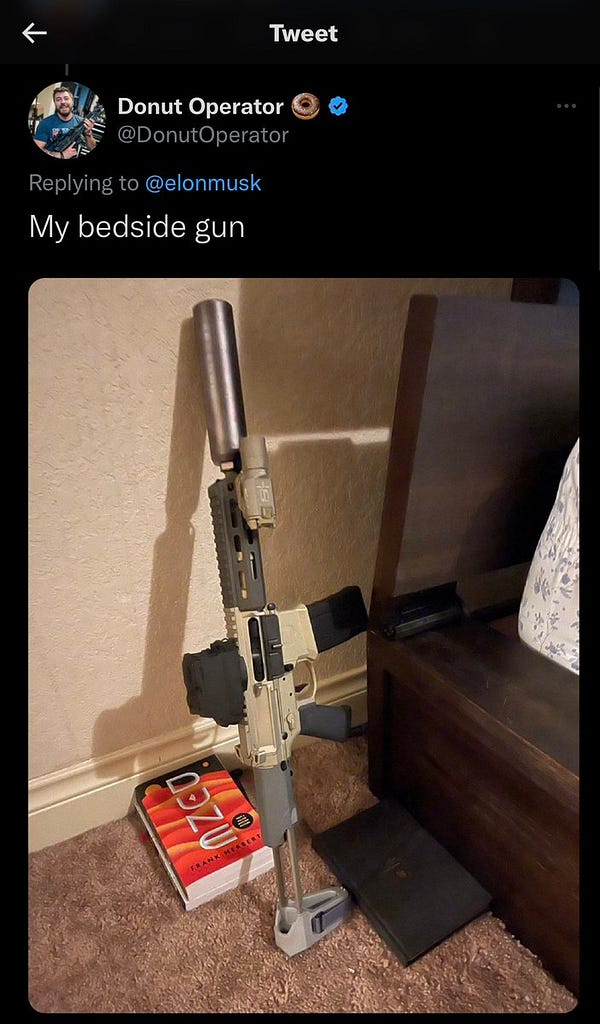

What’s on Elon Musk’s bedside table?

That is, for the record, a prop gun in the style of the gun from the video game Deus Ex. And those are caffeine-free Diet Cokes. This is not a bedside-table situation I feel positively about, but it might be better than those of Musk’s most ardent fans:

How is Twitter, the business, doing?

The reporting suggests: Not well. According to Chris Stokel-Walker, the payroll department, decimated by layoffs, is not having the easiest time paying employees on time:

Casey Newton reports that revenue is down significantly so far:

On Monday morning, a revenue analyst for Twitter in Europe shared some disheartening news. “We are seeing a significant decline in bookings,” the analyst posted in Slack, before sharing the numbers. Twitter’s ad revenue in Europe, the Middle East and Africa (EMEA) is down 15 percent year over year, he said, and weekly bookings are down 49 percent, according to screenshots shared with Platformer.

It was a grim update to an already dire set of forecasts. On October 31, in a Google Sheet created to track advertisers who had paused their campaigns amidst Elon Musk’s chaotic takeover of the company, analysts found that $15.7 million in EMEA revenue was already at risk. That included $12 million of anticipated losses in the United Kingdom, the company’s largest market in the region.

And the E.U. is threatening to ban Twitter from Europe unless Musk complies with the union’s new platform-regulation law:

Thierry Breton, the EU’s commissioner in charge of implementing the bloc’s digital rules, made the threat during a video meeting with Musk on Wednesday, according to people with knowledge of the conversation.

Breton told Musk he must adhere to a checklist of rules, including ditching an “arbitrary” approach to reinstating banned users, pursuing disinformation “aggressively” and agreeing to an “extensive independent audit” of the platform by next year.

Musk was warned that unless he stuck to those rules Twitter risked infringing the EU’s new Digital Services Act, a landmark law that sets the global standard for how Big Tech must police content on the internet. Breton reiterated that the law meant, if in breach, Twitter could face a Europe-wide ban or fines of up to 6 per cent of global turnover.