Greetings from Read Max! In todays’s newsletter, two items:

An exploration of “Elara Voss,” a mysterious figure haunting megaplatforms and L.L.M.s, and

a genealogy of Stomp Clap Hey, occasioned by discourse regarding the band “Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes.”

A reminder: Read Max is just one guy--me--and all of the reading, writing, thinking, and stupid chart-making is down to me. Producing 5,000 words every week is a full-time job, which I know because I keep failing to deliver on freelance assignments while I do this newsletter, and without the support of paying subscribers I wouldn’t be able to do it to nearly this level of quality (or stupidity). If you enjoy Read Max, to the extent that you would like to “buy me a drink” (every month), and want to support independent tech and culture criticism, please consider upgrading your subscription for the low price of $5/month or $50/year.

The legend of Dr. Elara

There are, as of this writing, 62 books credited to an “Elara Voss” available on Amazon: At least three collections of poetry; a dozen word-search activity books; a book advocating treating cancer with ivermectin; a travel guide to Krákow; a handful of romance novels; a “poetic novella about personal rebirth”; and a sci-fi novel, Genesis Protocol: Pale Blue Dot, in which one “Dr. Aris Thorne, a xeno-biologist, is sent to investigate this alien civilization that deems humanity obsolete.”

These are not all, we can assume, by the same “Elara Voss”--there’s also a fantasy series in Portuguese, a blank diary with a German title, as well as an album of piano music, Cherish. What’s more, there are hundreds of books on Amazon and other self-publishing platforms that feature a character named “Elara Voss,” among them Veil of the Bloodwight Syndicate, Gynarchy’s Collar, and Starlight Nexus by Kylian Quinn:

If you go on Instagram or Facebook or Twitter and search for “Elara Voss,” you’ll find dozens of accounts offering stock tips, “foot content,” “SEO gues posting service [sic]” and more:

What’s so odd about this is that--for a name now so common across the megaplatforms--before 2023, “Elara Voss” did not exist. There is no person named Elara Voss in the United States. No birth certificate has ever been issued under that name; if you search for it in public records databases, you’ll turn up no results. There aren’t even any characters named “Elara Voss” in any book published before 2023. Until two years ago, the two words didn’t ever appear next to each other even by accident.

But if you direct almost any L.L.M. to generate a sci-fi story or narrative for you, it will name the main character “Elara Voss”--or a similar variation like “Elara Vex,” “Elena Voss,” or “Elias Vance”--with an alarming degree of frequency.

Elara Voss is not a real person. Nor is she a public-domain literary character. Nor--yet--a figure of myth or folktale. She’s not really anything at all except for name: A string of tokens that has proven irresistibly attractive to a number of different large language models when responding to prompts involving character names and science-fiction and fantasy stories. That is, “Elara Voss” is the text that L.L.M.s seem to have have collectively arrived upon as the best response to a prompt like “what should I name the character in the story I’m writing?”

When, exactly, “Elara Voss” and its cognates emerged from the latent space to dominate the Kindle Unlimited store is hard to say. I’ve seen some people on Twitter hazily suggest that Elara and kin--let’s call them promptonyms, to coin a phrase--were present in GPT 3.5 (released in November 2022), but the earliest instance of the names I can find online dates back to August 2023, when an account “exploring realms through #AIStorytelling & #AIConceptArt” posted a character sketch of a “visionary physicist and AI researcher” named “Dr. Elara Voss.” (A “Dr. Elara Finch” and a “Dr. Elara Solis” each appear a few months earlier.) Voss appears a handful more times on Twitter in similar contexts over the next few months, and pops up on a fan-authored Warhammer 40k wiki as the name of the “highly respected leader of the Inanis 23rd Voidstalkers.”

But by the same time next year, Elara, Elena, and Elias Voss, Vex, and Vance had become inescapable, to the point that frequent users and A.I.-powered writing apps began to develop specific prompts to avoid them. The promptonyms reportedly appear in every major L.L.M.: GPT, Claude, Gemini, LLaMA, DeepSeek, and Grok. An A.I. tinkerer on Reddit playing around with L.L.M. benchmarks last August found that Google’s lightweight Gemma model used the name Elara “39 times in 3 separate stories,” and Elias “29 times in 4 separate stories.” None of the commenters were surprised: “every time I try using any models for creative writing, doesn't matter whether it's gpt-4, mistral, llama, etc, always the same names come up like Elara or Whispering Woods, etc.,” one wrote. (Alongside “Whispering Woods,” you can file “Eldora” as the name of a magic kingdom.) Elara Voss seems to be the promptonym generated most often, others like “Aris Thorne” (“Why is Dr. Aris Thorne everywhere?” one Redditor wondered) and “Elias Vance” are found frequently too:

In fact, a whole host of tropes and concepts seem to accompany Dr. Elara wherever she’s found. The prototypical “Elara Voss,” as described by a text generator, is a doctor, usually a physicist but sometimes a linguist or biologist. (Other times, she’s a spaceship captain.) She’s generally on the verge of a major breakthrough or discovery (often cosmic or even metaphysical in nature), or is researching some kind of “anomaly,” but is isolated, troubled, and sometimes “haunted” by what she’s learning. She’s often found “trembling” or her heart is racing; instruments near her are usually “pulsing.” The name “Erebus” often appears in Dr. Elara stories: a “Project Erebus” on which Dr. Elena Vex is working, or a mining colony named “Erebus-IX” to which Dr. Elias Vance must travel, or even a “rogue A.I.” called Erebus, “neutralized” by Dr. Elara Voss.

To the more esoterically inclined A.I. schizoposter, Dr. Elara’s omnipresence, and the consistency of the motifs generated around her, endow her with a kind of mythological or folkloric quality: She’s a divinity, or a culture hero, about whom a set of relatively predictable stories are told. (You can only imagine the kinds of quackery Jung or Joseph Campbell would have gotten up to, given access to L.L.M.s) In this capacity she joins other A.I. cryptids or tulpas--figures like the A.I. ghost “Loab” or the “glitch token” “petertodd”--in a sort of ever-raveling A.I. “lore” popular among influencers and some even researchers. There’s a strong culture of semi-ironic mysticism around L.L.M.s among people who both genuinely believe in their power and who also understand that creepy fanfic is a powerful marketing tool for the technology. (And that solid ironic-mystical tweets will go viral.)

Admittedly, I too have a hard time not giving in to the spooky pleasures of imagining a pantheon of A.I. tulpas emerging from the latent space, a new mythos derived from the hidden structures of our culture. But there are also less occult ways of accounting for the frequency with which Elara and her fellow promptonyms appear. As many people have pointed out, there’s a significant character in World of Warcraft named “Lilian Voss,” and the volume of text publicly available online about the WoW universe in the form of wikis, walk-throughs, and YouTube transcriptions likely gives the lore a gravitational pull in most models. If you trace back, e.g., Gemma’s decision-making process you can see that “character names,” as well as “science fiction” and “fantasy,” are all closely linked in the model to a “text about World of Warcraft” neuron, as Abram Jackson shows here and a user called beowulf shows here. (Similarly, there’s a character named “Elara Dorne” in Star Wars: The Old Republic, a voluminously covered M.M.O.R.P.G. like WoW. It’s a good reminder that L.L.M.s reflect “culture” in the narrow sense of “the culture of text publicly available on the internet in great volume.”)

As for her ubiquity across models, that’s almost to be expected. All the largest models are trained on effectively the same corpus--i.e., “almost all publicly available text”--and the processes by which they are made smooth and sanitary for public release sand down particular differences even further. (They’re also likely training on each other’s responses, which should lead to additional convergence.)

So you might say that Dr. Elara Voss is an emergent legend whose qualities reflect a deep mathematical structure underlying our culture. You might also say she’s a statistical agglomeration of science-fiction cliché borne of oversampling video-game wikis. I’m not sure that either of those views is wrong, precisely! What I do know is that we should enjoy her while she lasts: By the next generation of models, she’ll almost certainly have been eliminated. As much as we might enjoy the idea of A.I. lore, the companies selling the tech (as fiction-writing software, among other things!) don’t like the kind of consistency that points to something other than total magic occurring under the hood.

Where did “stomp-clap” come from?

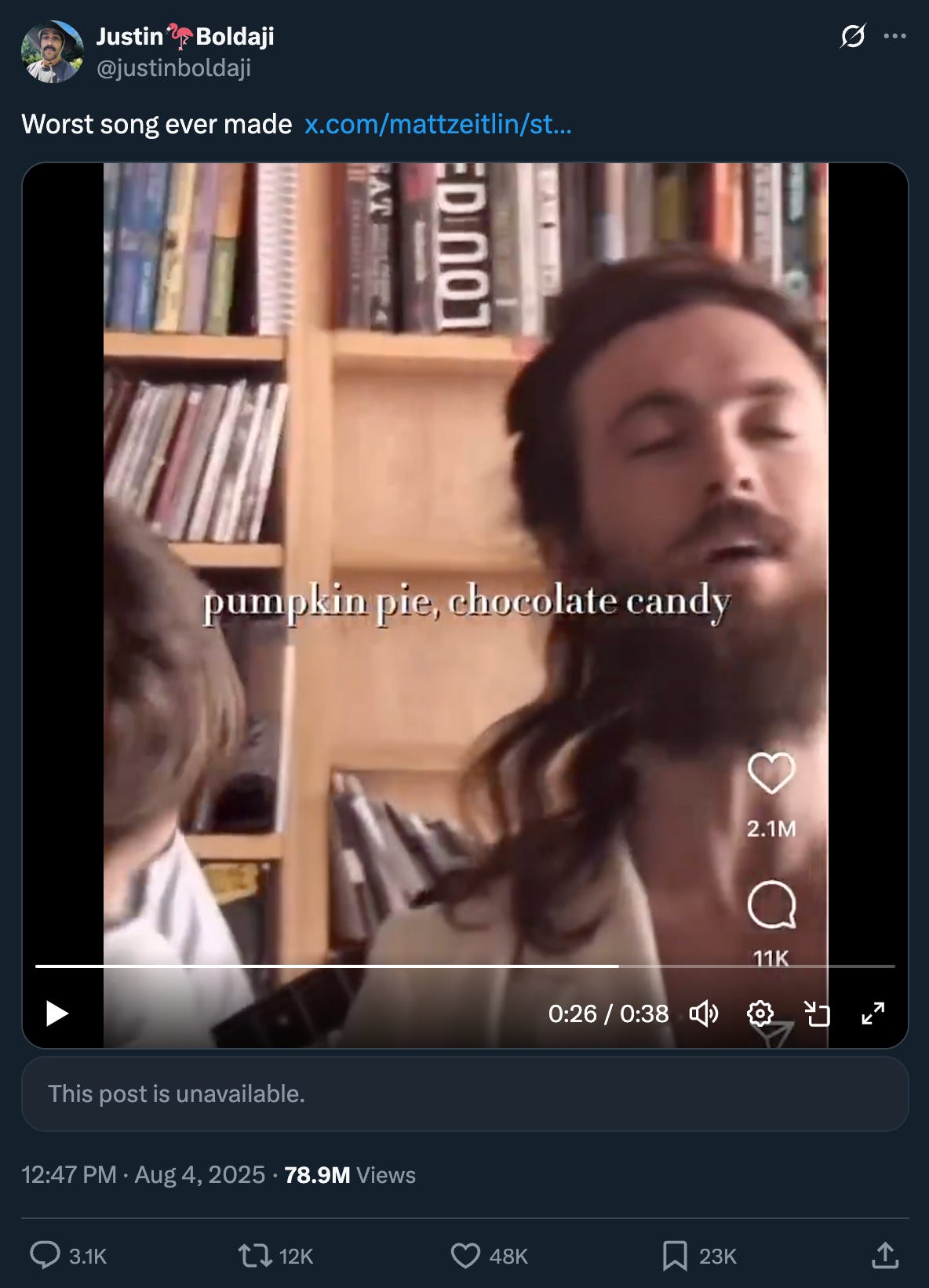

This week on Twitter a video of the band “Edward Sharpe and the Magnetic Zeroes” performing their hit single “Home” on NPR’s Tiny Desk in 2010 was widely circulated with the caption “worst song ever made”:

“Home” is only the worst song ever if you’ve never watched one of CatatonicYouths’ TikTok music compilations. But the video’s hold over Twitter, and the arguments and misconceptions it has generated, have convinced me that the song is nonetheless culturally important. Here, e.g., is someone describing “Home” as “stomp clap hey” music, a coinage generally used to categorize Mumford and Sons, the Lumineers, and other anthemic stadium-folk bands that dominated retail playlists in the 2010s:

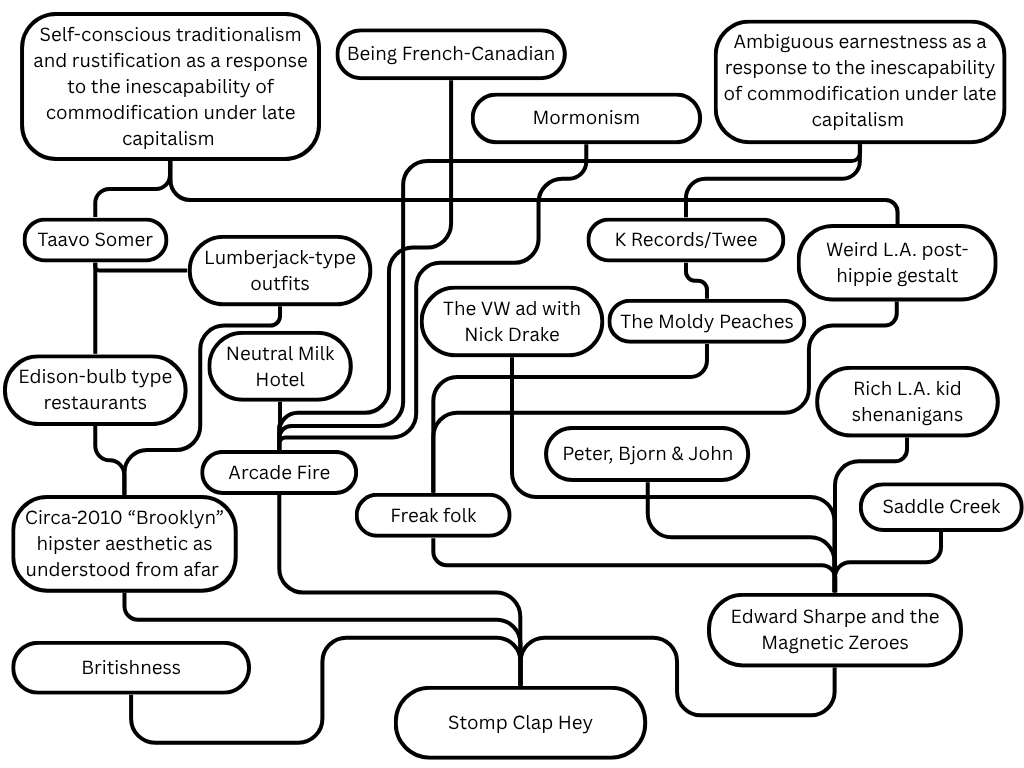

But is “Home” actually “stomp clap hey” music? A debate is currently raging on Twitter about the precise provenance of “stomp clap”: As other scholars have pointed out, musically speaking “Home” bears closer resemblance to a band like Peter Bjorn & John than it does to the car-advertisement bangers of a Mumford & Sons, and the ultimate stomp-clap template owes more of a debt to Arcade Fire than it does to Edward Sharpe. (“Stomp clap” is more or less what you get when you replace the French Canadian DNA in Arcade Fire with even more Mormonism, or, alternatively Britishness.) On the other hand, the down-home old-timey cosplay of the lyrics and vibe of “Home” (not to mention its success as a single) mark it as a clear cultural forerunner to stomp clap. It seems increasingly clear with hindsight that “Home” represented a kind of evolutionary link or turning point in the journey from Pitchfork Indie to Stomp Clap Hey--a band with feet planted in both worlds. (“Edward Sharpe” himself was formerly in an electroclash band called Ima Robot.)

But the actual genealogy of Stomp Clap, as a genre and an aesthetic, is much more diverse and intricate. To help people more fully understand the complex lineage of Stomp Clap Hey, Read Max has prepared the following diagram. Please share with anyone you know confused about where Stomp Clap Hey came from:

The flowchart has been updated since publication to better reflect the position of Mormonism in the genealogy of Stomp Clap Hey.

Previously in hipster studies on Read Max: What was the hipster?

Previously in anthems on Read Max: Fypcore and the Benson Boone-iverse

incredible edition of read max top to bottom

I think an important element of stomp-clamp-hey historiography is that the most crystalline example (and probably the one people were thinking of subconsciously when they coined the genre name) is that song by Of Monsters and Men, an Icelandic band. It's a perfect example because the whole thing is a completely abstracted sense of being "genuine" or "earnest" with no actual relationship to a historical referent. Intransitive authenticity.