What happened with Silicon Valley Bank?

Explanations, conspiracy theories, and jokes about Silicon Valley's big bank collapse

As is often the case, my quest to compose a thoughtful and wryly humorous weekly newsletter has been thwarted by my compulsive rubbernecking. Rather than work on this hypothetical column, I have been watching the legendary tech-industry bank Silicon Valley Bank suffer a bank run and collapse over the last two days, culminating in the announcement Friday that the bank would close and the FDIC would take control, creating the Deposit Insurance National Bank of Santa Clara to pay out insured depositors.

But my rubbernecking habits are subscribers’ gain! I’m going to share here what I’ve been reading and following as I try to understand what happened, what’s next, and whether this is “kind of funny” or “actually really horrifying,” or, possibly, and most likely, both.

What was Silicon Valley Bank?

Here’s a 2015 New York Times piece that gives you a sense of SVB’s position in the tech industry:

Silicon Valley Bank has maintained a dominant position among start-ups and venture capitalists in one of the most promising and lucrative corners of the United States economy. By the bank’s count, it serves 65 percent of all existing start-ups and many of the most prominent venture capital firms. […]

Silicon Valley Bank’s strategy has brought it into increasing competition with the large banks that want a piece of the technology industry. Though Silicon Valley Bank is relatively small — it has a $40 billion balance sheet, compared to $850 billion for Goldman Sachs — many analysts say they think the bank will maintain its competitive edge.

“They have the relationships and they understand how to work them,” said Aaron James Deer, an analyst at Sandler O’Neill.

One thing the Times article doesn’t mention is that SVB was entangled in the personal finances of many tech-industry workers and executives, as this thread from General Assembly founder Brad Hargreaves outlines. (Elsewhere in the thread Hargreaves predicts “mass layoffs” as early as today, Friday, but I would take that with a grain of salt.)

One thing SVB did not do, per its wealth management site, is sell wine or wine products! (Though apparently it did finance vineyards and wine makers.)

What happened to SVB?

The nutshell is that rising interest rates lowered the value of securities that SVB owned and led to some depositors withdrawing cash, and when the bank tried to raise more capital Silicon Valley panicked and effected a bank run.

A good, simple, low-jargon explanation for the basic balance-sheet problem can be found in Michael Hitzlik’s column for the Los Angeles Times:

The bank wasn’t watching its basket. It used its depositors’ funds, which were always repayable on demand, to buy long-dated Treasury securities. Bloomberg commentator Matt Levine properly calls this “boring maturity mismatches and a lack of deposit diversification.”

Investing in treasuries with distant maturity dates — anywhere from a year to 30 years out — is perfectly safe, since the U.S. has never defaulted. When the bonds mature, you can be 100% certain that you will receive your principal, plus the nominal interest.

In the interim, however, the value of those securities falls as interest rates rise (and rises as interest rates fall). If you have to sell too early, you can take a bath. That’s the fundamental Silicon Valley Bank story. […]

Starting in early 2020, the Fed put interest rates on an upward trajectory, raising rates by 4.75 percentage points in 2022 alone. This rattled the bank’s depositors, who started withdrawing cash. Their interest-related expenses were rising and their options for raising new rounds of funding were shrinking, as the venture firms that had been keeping them afloat slowed down their investing.

On Thursday, as the bank announced that it was seeking new capital, venture capitalists such as Peter Thiel advised their portfolio companies to pull their money out, intensifying the rush for the exits.

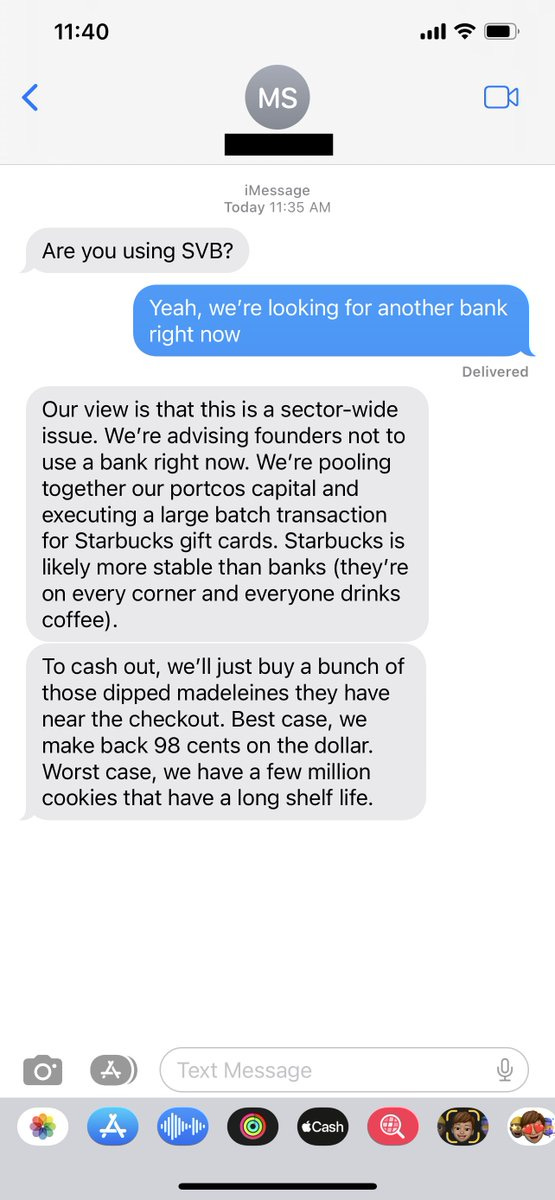

For a detailed account, which may require some Googling for the definition of terms, I recommend this longer newsletter from Net Interest, which highlights, among other things, a key structural problem: High-speed online banking crossed with a “concentrated customer base,” i.e., a bunch of gossipy VCs and tech executives texting each other FUD:

We’ve never really had a bank run in the digital age. Northern Rock in the UK in 2007 predated mobile banking; it is remembered via images of depositors lining up (patiently) outside its suburban branches. In 2019, a false rumour on WhatsApp started a small run on Metro Bank, also in the UK, but it was localised and quickly resolved. Credit Suisse lost 37% of its deposits in a single quarter at the end of last year as concerns mounted about its financial position although, at least internationally, high net worth withdrawals would have had to have been phoned in rather than executed via an app.

The issue, of course, is that it is quicker and more efficient to process a withdrawal online than via a branch. And although the image of a run may be different, it is no less visible. Yesterday, Twitter was alight with stories of venture capital firms instructing portfolio companies to move their funds out of Silicon Valley Bank. People posted screenshots of Silicon Valley Bank’s website struggling to keep up with user demand. Greg Becker, the bank’s CEO, was forced to hold a call with top venture capitalists. “I would ask everyone to stay calm and to support us just like we supported you during the challenging times,” he said.

The problem at Silicon Valley Bank is compounded by its relatively concentrated customer base. In its niche, its customers all know each other. And Silicon Valley Bank doesn’t have that many of them. As at the end of 2022, it had 37,466 deposit customers, each holding in excess of $250,000 per account. Great for referrals when business is booming, such concentration can magnify a feedback loop when conditions reverse.

Or, fine, you can just read Matt Levine:

And so if you were the Bank of Startups, just like if you were the Bank of Crypto, it turned out that you had made a huge concentrated bet on interest rates. Your customers were flush with cash, so they gave you all that cash, but they didn’t need loans so you invested all that cash in longer-dated fixed-income securities, which lost value when rates went up. But also, when rates went up, your customers all got smoked, because it turned out that they were creatures of low interest rates, and in a higher-interest-rate environment they didn’t have money anymore. So they withdrew their deposits, so you had to sell those securities at a loss to pay them back. Now you have lost money and look financially shaky, so customers get spooked and withdraw more money, so you sell more securities, so you book more losses, oops oops oops.

As Armstrong puts it, SVB had “a double sensitivity to higher interest rates. On the asset side of the balance sheet, higher rates decrease the value of those long-term debt securities. On the liability side, higher rates mean less money shoved at tech, and as such, a lower supply of cheap deposit funding.”

Also, I am sorry to be rude, but there is another reason that it is maybe not great to be the Bank of Startups, which is that nobody on Earth is more of a herd animal than Silicon Valley venture capitalists. What you want, as a bank, is a certain amount of diversity among your depositors. If some depositors get spooked and take their money out, and other depositors evaluate your balance sheet and decide things are fine and keep their money in, and lots more depositors keep their money in because they simply don’t pay attention to banking news, then you have a shot at muddling through your problems.

What happens next?

Based on how founders and investors are reacting on Twitter, the biggest perceived risk appears to be that many companies rely on SVB in one way or another to issue payments to employees. Rippling, a popular startup payroll processor, has moved some of its operations to JP Morgan, according to its CEO --

-- but some companies, like the medical testing and data company Flow Health, are still waiting to see the resolution:

Janet Yellen says that “the banking system remains resilient and regulators have effective tools to address this type of event,” which is both true but also, like, what else is she going to say? The hope is that SVB can find a buyer by Monday; if it can’t, the FDIC is on the hook. Depositors with up to $250,000 are insured by the FDIC, of course, but apparently more than 90 percent of the bank’s deposits are still uninsured:

Bloomberg’s Tracy Alloway has a thread on some longer-term reactions:

What is the Peter Thiel connection?

A number of outlets have reported that Peter Thiel -- or, more specifically, his Founders Fund -- was fomenting the run on SVB by advising companies to pull their money.

Founders Fund, the venture capital fund co-founded by Peter Thiel, has advised companies to pull money from Silicon Valley Bank amid concerns about its financial stability, according to people familiar with the situation.

The firm told portfolio companies that there was no downside to removing their money from the bank, according to the people, who asked not to be identified because the information isn’t public.

Why would Thiel want to do such a thing? Bloomberg’s Max Chafkin suggests it’s simply ideological:

A more fun conspiracy theory might be that Thiel is looking for an edge for the semi-competitors in his portfolio:

An even more fun conspiracy theory is that it’s a full Count of Monte Cristo pursuit of his vendetta against Gawker:

Christ, I now have three train crashes that I am watching. FTX and Crypto, The Twitter saga, and now the failure of SVB (I drive by it all the time).

Gonna need more popcorn

Great post, Max. Another factor I can see at play is the Greater Fool Theory, which is when investors know they’re taking or sustaining a risk but figure they’ll always be able to get out of a run before the morons at the end of the chain. With SVB, I guess quick online liquidity and ultrafast online news transmission mean that some of the fools never expected to be fools.