Is Iran War discourse as stupid as Iraq War discourse?

PLUS: The future of sophisticated, hostile pricing

Greetings from Read Max HQ! In today’s newsletter:

Some thoughts about the increasing sophistication (and hostility) of pricing technologies; and

answering the question: Is the run-up to the Iran War we seem intent on joining as stupid as the run-up to the Iraq War?

A reminder! Read Max is my full-time job. I’m able to focus on it--by which I mean reading, writing, thinking, reporting, talking to people, and all the other activities that go into making this newsletter--because more than 3,000 people find it valuable enough to pay for a subscription. But because I lose some subscribers every week (“churn,” an inevitable feature of subscription businesses), I need to keep adding new ones in order to stay above water, let alone to grow. So if you’ve been reading for a while--or even just for a few weeks--and have found what I’m doing valuable to you, please consider subscribing. At $5/month and $50/year--which, not to brag, has stayed low and stable for five years, even as other Substacks are charging $8/month by default!!--think of it like buying me a beer or espresso drink a month, or roughly ten beers or espresso drinks, or some combination thereof, a year.

Pricing the future

I recently joined the Economic Futures Cohort at the Economic Security Foundation, a think tank dedicated to advancing “ideas that build economic power for all Americans.” In exchange for a stipend, I’ll be attending three E.S.F. briefings over the next few months and writing about what I’ve learned and how I’m thinking about it. (E.S.F. has no editorial oversight; I have complete control over what’s published in this newsletter.) The most recent briefing was about prices.

I have always thought that a good microcosm for the affective experience of life in the 21st century American economy is flying commercial: You can go almost anywhere you’d like cheaply, so long as you’re OK with being herded and packed into a tube; stripped of any kind of dignity; charged extra for meager comforts once widespread and free; acutely aware of how much better the people richer than you have it; and suspicious that everyone around you somehow got a better deal for an identical experience.

It’s in the prices and fees that I think the microcosmic aspects of flying really emerge. The closely guarded impenetrability of airline price-setting mechanisms exacerbates the sense both that there’s always a better deal out there, and that you’re probably getting screwed. And the truth is, you probably are: A couple weeks ago the website Thrifty Traveler reported that American, United, and Delta “are penalizing solo travelers with higher ticket prices than you can book when traveling with a group,” in some cases twice as high, a news story that saw no small amount of circulation among my single friends in group chats.

To combat this sense, everyone who flies with regularity has some kind of occult strategy, often based on theories about the systems that undergird airline pricing, for obtaining the lowest possible cost for their tickets. (Check this website. Use this browser. Use this VPN. Check eight weeks in advance. Check two days in advance. Join this rewards program. Get this credit card.) But even when you find a cheap face-value ticket you find yourself contending with the fees to understand the total price: Are they going to charge me to check a bag? To carry on a bag? To pick a seat? To consume a little cardboard “Mediterranean Snack Box” with eight almonds and four vacuum-packed olives?

There’s a certain genus of spreadsheet-wielding masochist who finds this kind of price-shopping invigorating. But I think most of us find it, at best, annoying, and, at worst, exhausting and humiliating. I suspect a lot of people don’t even bother with attentive price comparison, and find themselves paying a lot more than they should in up-front costs or day-of-flight fees--a kind of consumer tax on anyone unwilling or unable to expend the cognitive energy necessary to get a comprehensive understanding of the airplane ticket marketplace.

But at least with airline tickets you’re afforded the incredible experience of flying through the air to a destination thousands of miles away. It is hard not to notice the airline standard of impenetrable, mystifying pricing--and the attendant, obligatory superstitions--increasingly prevalent across a wide range of goods. The kind of dynamic, time-and-demand-sensitive pricing enabled by constant connectivity is now standard (and deeply irritating) across the concert-ticket industry, but also creeping in at restaurants and, maybe, grocery stores--sometimes even combined with surveillance techniques, designed to raise or lower prices specifically based on the demographic profile guessed at by whatever systems exist under the hood.

There is, to be fair, an argument beyond “greed” in favor of dynamic pricing: It increases a given market’s efficiency, encouraging supply to meet demand. Uber, by introducing the world to “surge pricing,” has done some incredible work over the last 15 years paving the ideological road to universal dynamic pricing. But in practice, modern dynamic pricing--especially when deployed in concert with search and surveillance--is often explicitly hostile to consumers, steering them toward more expensive options and throwing out highball quotes.

It’s also, in all cases, implicitly hostile to consumers, obligating a much higher level of attention and involvement to the simple act of buying something--or, as with airline tickets, extracting a “tax” on anyone without the time and inclination to do so.

Some of this, at least, is straightforwardly illegal--especially when algorithmic pricing rises to the level of price-fixing (as is said to have happened with frozen potatoes recently) or when it’s designed to manipulate competitors’ prices, as the F.T.C. has accused Amazon of doing. But a lot of it isn’t. And you can imagine asking: Why should it be? The unfortunate truth about airline-ticket pricing is that even as buying and flying both get worse, even as baggage and food and comfort are disaggregated as fees, Americans consistently respond by buying more tickets. What else are the airlines supposed to learn from that?

What bothers and worries me most about the increasingly complex and annoying pricing systems enabled and deployed by the software industry is the way they reorient our relationship to the world around us. Prices already loom large in the lives of Americans because of the extent to which we understand ourselves as consumers above all else--rather than, say, citizens, workers, human beings, posters, or whatever. But I’ve written before (too much at this point) about the way the tech industry’s various mediations increasingly turn us from consumers into gamblers and speculators--risk takers riding waves of volatility to collect some gain. (But almost always, at the end of the day, rinsing us all as suckers.)

The transformation of relatively stable prices into individualized, tech-driven moving targets pushes us even further into the realm of speculation and wagers. Attaching volatile, up-to-the-minute surveillance-driven prices to any good or service is a good way to put it in the same basket as securities, crypto tokens, wagers, and online reputations. What happens when buying anything at all requires the same level of attentiveness, care, and planning with regard to prices that most of us bring to flying commercial, buying concert tickets, or speculating on securities? A life spent trying to predict when bread and eggs are going to be the cheapest, and which family member’s credit score will earn them the best deal.

How stupid was the run-up to the Iraq war?

As most readers are probably aware, the United States is maybe, sort of, at war with Iran, or not, depending on which Donald Trump Truth Social post you have read most recently. The “discourse” about this conflict, such as it is, led by the president’s senescent lack of clarity and an almost entirely witless political and media establishment has been pretty mind-bogglingly stupid; even Tucker Carlson managed to come off well compared to Texas Senator Ted Cruz, who was unable to state even basic facts about the Islamic Republic in an interview with Carson this week.

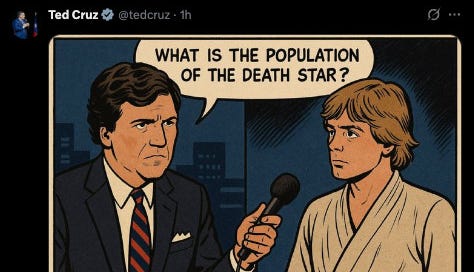

In response to this (the latest in a long line of humiliations visited upon him by fellow conservatives), Cruz posted an A.I.-generated cartoon of Carlson asking Luke Skywalker “What is the population of the Death Star?” leading Rolling Stone politics reporter Nikki McCann Ramírez to wonder if the Iraq invasion debate was “this stupid”:

First let me commend Ramírez for crafting some of the most Bluesky-specific bait I have ever seen in asking a website filled with college-educated news-reading liberals between the ages of 35 and 50 to expound at length on the run-up to the Iraq War.

Now, let me take the bait: In aggregate the “Iraq invasion debate” was much, much stupider. But the stupidity of this contemporary “debate” is different in quality as well as overall quantity, in ways that I think are instructive.

I suspect that most of my readers are 35-to-50-year-old Bluesky liberal types, or at least adjacent, and don’t need detailed reminders of what the run-up to Operation Iraqi Freedom was like. (I would say, in support of my own case, that “debate” is not really the right word because every situation in which it was “debated” domestically took quite literally the form of the famous Onion point-counterpoint: “This War Will Destabilize The Entire Mideast Region And Set Off A Global Shockwave Of Anti-Americanism vs. No It Won’t.”) But the main thing I would emphasize, I think, was that the “manufacturing consent” phase of the Iraq War was particularly stupid because it worked. Invading Iraq had overwhelming support among American citizens and institutions, a fact reflected not just in polling but in the way politicians spoke and acted and in the columns and articles of basically all not-explicitly-left-wing media of the time and even in the actions of the institutional entertainment industry. Almost every single thing you read or watched or heard about was unimaginably stupid. (The best way to understand what this felt like is to read David Rees’ unimpeachable classic Get Your War On.)

It’s true that the stupidity already gathering around this war is highly concentrated in its central locations. Worse, it’s all being conducted over social media, a conduit that has never in history made any discourse more intelligent. The weeklong dance over intervention undertaken by our obviously sunsetting president would be among the stupidest things I’ve ever seen if it was only conducted in vague interviews. But the fact that we are waiting for “Truth Social” posts from the president to understand whether or not we’re at war--while the Vice President tweets simpering defensive statements about how the president is “my friend”--is stupid in a way that at least rivals some of the stupidest moments of Iraq War discourse.

The good news is that the manufacturing-consent phase for our hypothetical war in Iran is, so far, quite different: A large majority opposes any kind of U.S. involvement, and a number of Democrats have staked out public positions against it. Even The New York Times thinks, at the very least, that we shouldn’t “rush into” war. It’s much easier to read and watch and hear things that feel, at least, sane, if not actually intelligent. Unfortunately, what feels quite bad--orthogonally to how stupid it is--is it’s not clear how much any of that matters, at the end of the day. All we can do now is refresh Trump’s Truth Social feed.

One of the most striking and slightly queasying things about the Cruz-Tucker interview was how many times they both felt it necessary to pause awkwardly and profess how much they both "love Trump". One definite difference between the Iraq buildup and now is you didn't have journalists and politicians feeling they had to emotionally nursemaid the President so he wouldn't get triggered and start a war.

Hotel booking is another example of dynamic pricing strategies.